Interview with De Nichols

How does Senior Product Inclusion UX researcher on the YouTube team at Google, artist, public speaker, community organizer, and author De Nichols find balance in her busy life? Listen as designer De Nichols and interviewer Journee Harris discuss work and well-being.

Listen

De Nichols Interview Transcription

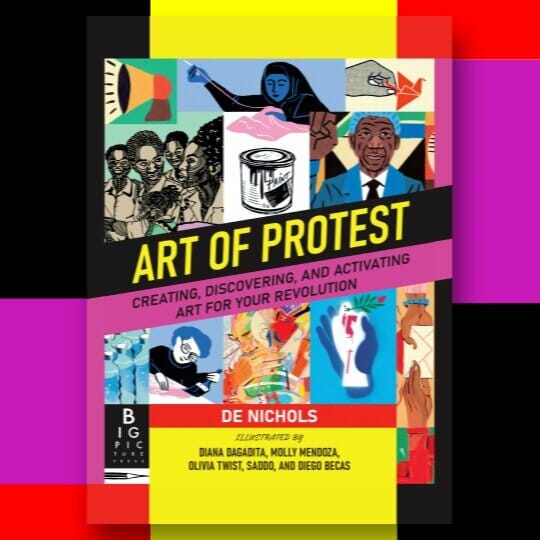

De Nichols: I am De Nichols. She, her are my pronouns. I will accept they, them as well. I am currently based in Chicago. I’m a Senior Product Inclusion UX researcher on the YouTube team at Google. And, I also am the author of a new YA book, Art of Protest.

Journee Harris: Let’s start from the beginning. Where did you grow up?

De: I grew up in rural Mississippi. I was born in Chicago, but my mother moved my older brother and me to Mississippi, to the Delta, to Cleveland, where my elders are, where my grandparents still live today. And that area was formative for all the work that I do today. So in many ways, rural America is a microcosm of all the issues that we witness and experience in larger cities and the larger context of society at large. And that was the case for me too.

Journee: So, in Mississippi, how was your experience in school? Were you encouraged to be a creative person, or what were you encouraged to do and be when growing up in school?

De Nichols: So in Mississippi, they used to have a program called Project Pass, and it’s for students who are tested as gifted students. And so, I was in the gifted student program as a kid, which meant that I had to go to two schools at the same time. I went to my school because it was a Black school. You know, it was the school on my side of town. But then I was bussed over to another town where I got all of this extra enrichment. And I was learning about Roman and Greek mythologies in third grade. And that was something that, you know, I wasn’t exposed to in my school. And so my early education gave me a glimpse of what, what folks call Black exceptionalism, you know, being a good Negro and young gifted and Black, like all of that stuff.

But it also made me realize that I had to balance being fully me, and that came with a lot of bullying. I was Black and smart and not humble about it as a kid. I was the student raising my hand at every question. I didn’t shy away from that, so I got into a lot of fights. I was supported in the sense that my teacher saw something more in me than just defending against bullies. And they did nurture my creativity, but it wasn’t necessarily just visual craft that they were nurturing. I got a lot of that from home, from my family. Especially my grandmother. What they nurtured in me was the power of the narrative in learning how to write and be a storyteller. I got that from my teachers.

Journee: You said your family nurtured your more creative visual craft. Did your family members also have a visual craft of their own that you were able to learn from and experience?

De: No, my grandmother was the most creative person in my family growing up. She was a dollmaker, and she’s a writer too. She writes a lot of the eulogies, like for funerals, and it’s made her rise to this level of prominence in our hometown because everyone goes to her when they want their life story celebrated and done well. I come from a family of ministers, so we’re all great at the spoken word. But when it came to visual arts, they more so just recognized a curiosity and talent within me early on. At first, I got in trouble for doing things like writing and drawing doodles on my great-grandmother’s walls. But every single Christmas and birthday, they were gifting me with the tools, with crayons, with markers, with everything that I needed to bring all of my ideas in my head to life. As a kid, I would keep this little red notebook of poems and stories and all the books that I wanted to write, but I would also illustrate the characters in that. My family saw that and just kept nurturing it.

One of the things that young designers who are at the intersection of two passions is don’t be afraid to bring that other into it and start experimenting with what a whole new thing could look like. I’m a big music lover of remix culture. I would say apply that to the field, to the things that you’re passionate about. Take those two things that seem disparate, mash them up, and create something beautiful.

Journee: So what happened after high school? Where did you go to college? Did you relocate? Did you leave Mississippi?

De: If I could skip back a little bit, my mom was a single mom. She moved my brother and me from Mississippi to Memphis when I was in fifth grade. In Memphis, we had schools with arts programs. So I ended up going to a creative and performing arts high school, and that’s when I started to find my visual voice of going from just the ideas in my head and connecting the dots between different histories that I knew about Memphis.

Memphis is one of the bedrocks of the civil rights movement. This is where Dr. King was murdered. So there’s a legacy here that my art teachers in high school nurtured. When I was ready to transition to college, I ended up getting a full academic ride to Washington University in St. Louis to further develop my visual voice, not as an artist, rather, as a communications designer or a graphic designer. A big part of that was realizing that (and this came from my mom) I needed to find the creative thing that you can do that can also lead to a career. Pivoting from visual art to design in college was that critical point because that introduced me to a whole new language, a whole new ballgame of possibilities. But even on campus, I was a student organizer, so that link between visual practice, injustice, and social change at large was always linked in my journey there.

During my senior thesis, one of my professors looked at my body of work, and he was like, “you should not be a designer. You should be someone out there working with the people.” And as hurtful as that was at the time, he was right because I ended up going on this journey of working with the people and using design as that catalyst to elevate other people’s visual voices for social change.

Journee: What was your transition from being a designer working strictly in design to working with the people and incorporating design into that?

De: I was accepted to work for Teach for America, and right before the Summer Institute, I quit. It was just a gut feeling that I should not be going into the classroom. Like there’s more that I wanna do. Then I ended up getting accepted into this program called Project M Lab, a program that takes young designers and plants them in rural America or someplace that’s kind of off the map. And for half of the summer, we have to go in as social entrepreneurs, as design entrepreneurs and help that community problem-solve issues. Back then, that sounded like a glorious opportunity for someone who likes social change, community service, and stuff, but it was transformative in the sense of opening my eyes to that type of savior mentality that existed amongst or within the field. My cohort ended up getting kicked out of a neighborhood. And I left that experience being like, I wanna do this work, but I wanna do it where I’m not causing harm, where I’m not necessarily fueling the same type of trauma that people are already experiencing. So I transitioned to grad school, where I studied social work. I went back to St. Louis to Brown School at Washington University, and it gave me the space to learn how to do this work well and do it right.

Photo by Steve Truesdell, Riverfront Times

Journee: Based on your experience, do you have advice for people with interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary interests that feel pressure from their parents, family, or just the world around them to pursue only one thing? What would you tell someone who wants to explore and do something wildly different?

De: I would tell them to be entrepreneurial about it. I was a misfit in my program. I had to be comfortable with being a misfit and using the resources and leveraging the connections that I had to define and carve the work that I wanted to do because back then, the title of Social Impact Designer didn’t exist in anybody’s job descriptions. To carve that lane for myself, I had to hustle, and I had to put it into practice. One of the things that young designers who are at the intersection of two passions is don’t be afraid to bring that other into it and start experimenting with what a whole new thing could look like. I’m a big music lover of remix culture. I would say apply that to the field, to the things that you’re passionate about. Take those two things that seem disparate, mash them up, and create something beautiful. That was definitely part of my journey, but it came with a lot of openness to learning both sides. Like when, when you’re trying to merge two things, you have to be good at connecting the dots and seeing where those disparate moments are opportunities for either something new or a fusion that it’s better than the individual parts.

Journee: You’re coming out of an experience where a savior complex overtook leadership and helping others. So how did the school of social work help?

De: There were so many ways. The Brown School at Washington University is very good at bringing in experts who can help nurture the various facets of what any of the student’s passions might be. It’s also good at convening thought leaders for us to engage with. For example, when I was a student in my first year of grad school, the Clinton Global Initiative came to St. Louis, and my academic deans, my advisors, made sure that we were involved. That platform pushed me into the national spotlight because I led two projects that were a part of the Clinton Global Initiative back then. So I think the school of social work was a catalyst for me going beyond the local scene and connecting with all of these people across the nation and in some ways across the world to learn best practices and do this work well.

Journee: Can you talk a little bit about those projects you were working on?

De: Design Serves was the first project that was a part of the nonprofit that I started in grad school called Catalyst by Design, which then pivoted as a for-profit called Civic Creatives that I led since 2013. Design Serves had a very simple mandate of teaching young people in our local neighborhoods design skills so they could help envision and enable new prototypes of what community living could entail. By the time I pitched it to be a part of the Clinton global initiative, I had a team, we had partnerships, and we had done the work to set it up for success. We ran a few cohorts of that program. And at the time, I was really into storytelling. I hosted this monthly storytelling night called United Story of just bringing people from different perspectives on a topic to have an open mic about their personal experiences, not necessarily their opinions. We did a few iterations of United Story, and we pitched that to the Clinton global initiative as well, and that got selected. So those two projects defined my grad school experience, but they also led to the firm that I ultimately created.

Journee: That is so, so cool. So what came after grad school?

De: A few things came out of that. One was a double life because while I was my, while my team and I were founding Catalyst by Design, which is now Civic Creatives, I was also working full-time as a museum educator at our contemporary art museum, leading community and school programs. So I had access to all of these art supplies. I even had my own art bus that I would drive around town to do public projects with people. And after grad school, I stayed in St. Louis for a few more months. And in August of that year, this was 2014 on August 9th. That’s when Mike Brown was murdered. As a person freshly out of grad school, equipped with a lot of leadership skills, I hit the ground running with a team of artivists once the protests broke out in Ferguson. I was able to help supply protestors on the ground with art supplies to make their posters and stuff on the spot.

We also formed the Artivist Collective, and between August 9th, 2014, and the end of 2015, we had already created or co-created over 80 projects with protestors and activists and community members across the region. There was a lot of work that we were doing that got national attention. One of those projects, the Mirror Casket, even got collected, but the Smithsonian and the seven of us who are on that core team, a lot of us are still doing the same type of work today. I’m still organizing. I’m a core organizer of Design as Protest. So instead of just organizing with other artists, I’m organizing with designers across and within the design field.

The spirit of all of those three lives as an entrepreneur, artist/designer, and social worker coming together has been such a defining identity to have in this world. And that’s shifting right now, as I said, I just joined Google. Like, I just went corporate by joining the YouTube team. But in many ways, I’m still doing a lot of the same work within this team centering racial justice. Instead of doing it in the built environment with all of my comrades, with designers’ protests, I’m doing this work in the digital space, thinking about the virtual environment.

De Nichols by Sarah Swaty

Journee: Before we get into your corporate work, I wanted to ask about balancing being an organizer and working full-time. How do you take care of yourself? Can you speak a little bit about how you support your livelihood balancing all of these identities and all that you do?

De: The livelihood part came easy by being an entrepreneur, by having a design firm centered on not just the aesthetics of what something could be or the theory of what something could be, but the strategy and action. We took a BOGO approach. We asked our clients to help select which one of the initiatives we’re working on on the ground. Do you want us to use a portion of this revenue to support? By instituting this sense of all of this money that we earn, a portion of this goes back to the community. That was a sustainer. That was a model that worked very well. Because that meant that not only could I dedicate my time to being on the ground with people being pro bono, but also meant that I wasn’t just bringing my time; I was bringing money. I was bringing resources, skills, and sometimes other people along the way. But it came with a lot of sacrifices. I was not always good to myself. Back then, burnout was real.

I stretched myself way too thin to the point where I wasn’t able to take good care of my physical stuff. My romantic stuff, like my love life. I’ve never been in love. I haven’t had relationships that have lasted because I was such a workaholic back then and didn’t allow space to be soft. I was always just focused on everything else. I thrived, I was celebrated, and I had a lot of fun. I traveled a lot. I loved the freedom of that, but that came with that sacrifice of nurturing something that it took me so long to realize what’s missing and that I needed that sense of companionship, someone to come home to and just be with without an agenda. It made me realize that there were a lot of folks in my life who I was valuable to only because of what I could do for them or what I could create with or for them. That became too transactional for me. And so, my mental health was not well with making all of those realizations. And my physical self was not well. Throughout all of that, I had fibroids and very bad Endometriosis. And a lot of stress-induced gut issues that I still feel to this day. And by the summer of 2019, I ended up getting a hysterectomy because the fibroids had formed around my ovaries so dramatically that it was pressing on my bladder, pelvis, and all of these other body parts. I was in excruciating pain all the time. I was just forcing myself to push through the pain, and I cracked. I realized something had to change. This life that I’ve made that I’ve loved is not sustainable for my health. So I quit everything and decided then and there that I was going to treat myself to a vacation in South Africa. During that time, I decided to write an application for The Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

I ended up getting the fellowship at Harvard and quit everything and ended up getting the hysterectomy in the summer of 2019. And that changed my life. Wow. The sense of energy and focus clarity around who I wanted to be manifested itself. Entrepreneurship is no longer for me. This hustle, this grind, it’s not what I wanna do. I wanna make space to be still and able to do this work with passion. But not be burdened by carrying so much of the load and wearing so many of the hats and my role now at, at Google, I got one job, research, you know, like do this one thing and do it well. And I’m just in a better place because of that.

Journee: I want you to speak about the pros of stepping away and stepping away from your pride, even working with or working for someone else that gives you more time to have a life.

De: I mean, for me, it is a balance. I realize that I can let go of my ego, of my name being on everything. I can let that go. I have done well with my journey. I am proud of the work that I have done with others, and I can allow myself the grace to not always be that person, be that version of myself. So stepping into this pivot has been seamless. It has been liberating to go work for someone else. Primarily because everything that I’ve done has led to this point has equipped me for this role. I can’t speak a lot about what I do at YouTube for many reasons, but I will say that I didn’t stop being an entrepreneur even though I let my practice go.

My role is brand new to this company, and I get to be an entrepreneur. I get to help create something within this space that will have just as much impact, if not more, because we’re scaling, you know, we can scale globally. So I think it is less of a give and take, like what did I lose? What did I gain? And it’s more of like, how do I balance, how do I hold this? Going to work for someone, I had to articulate my conditions to make a case for me being there and it being a fit for me. And part of that was, I’m not gonna wear more than one hat. Here’s the job description. I will do this part well. Here’s what I feel my value is. And they, if you’ve heard about Google, they are generous. They, whew. Perks, perks. I earned more than I would’ve ever earned by running my firm. And I can say that and not feel shame or embarrassment about that because this is a huge company. But the thing that I would say to someone is you have to know yourself, you have to know where you are in your life and what will fulfill you in this life. And in whatever season or chapter that you’re in. For me in this chapter, I wanna nurture love. I wanna nurture and cultivate family. I want to breathe a little bit. I don’t wanna hustle all the time.

A lot of that back then, and still now, is glorified. Burnout culture, being booked and busy, people glorified that stuff. What I realized after doing it for so many years and being on the go all the time was that rest is just as important. I am no good if my tank is empty. Finding the position that will allow you to exist and bring your full self to any space. I think that is the goal.

In 2023 De Nichols joined the New York Google/YouTube office and currently lives with her fiance in the New York metro area.

Journee Harris

Urbanist, Researcher & Storyteller

About the Interviewer

Journee Harris is a Storyteller, Urbanist, and Community Development professional based in Cambridge, MA. She is a first-year Master in City Planning student at MIT and a proud alumna of Howard University, where she earned her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology. Journee has worked in the non-profit sector, focusing on public space, housing, youth development, historic preservation, and equity in the built environment for over seven years.

Music: Purple Dream by Ghostrifter bit.ly/ghostrifter-yt | Creative Commons — Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported — CC BY-ND 3.0 | Music promoted by https://www.chosic.com/free-music/all/