Trust

Community Series

By Sascha Mombartz

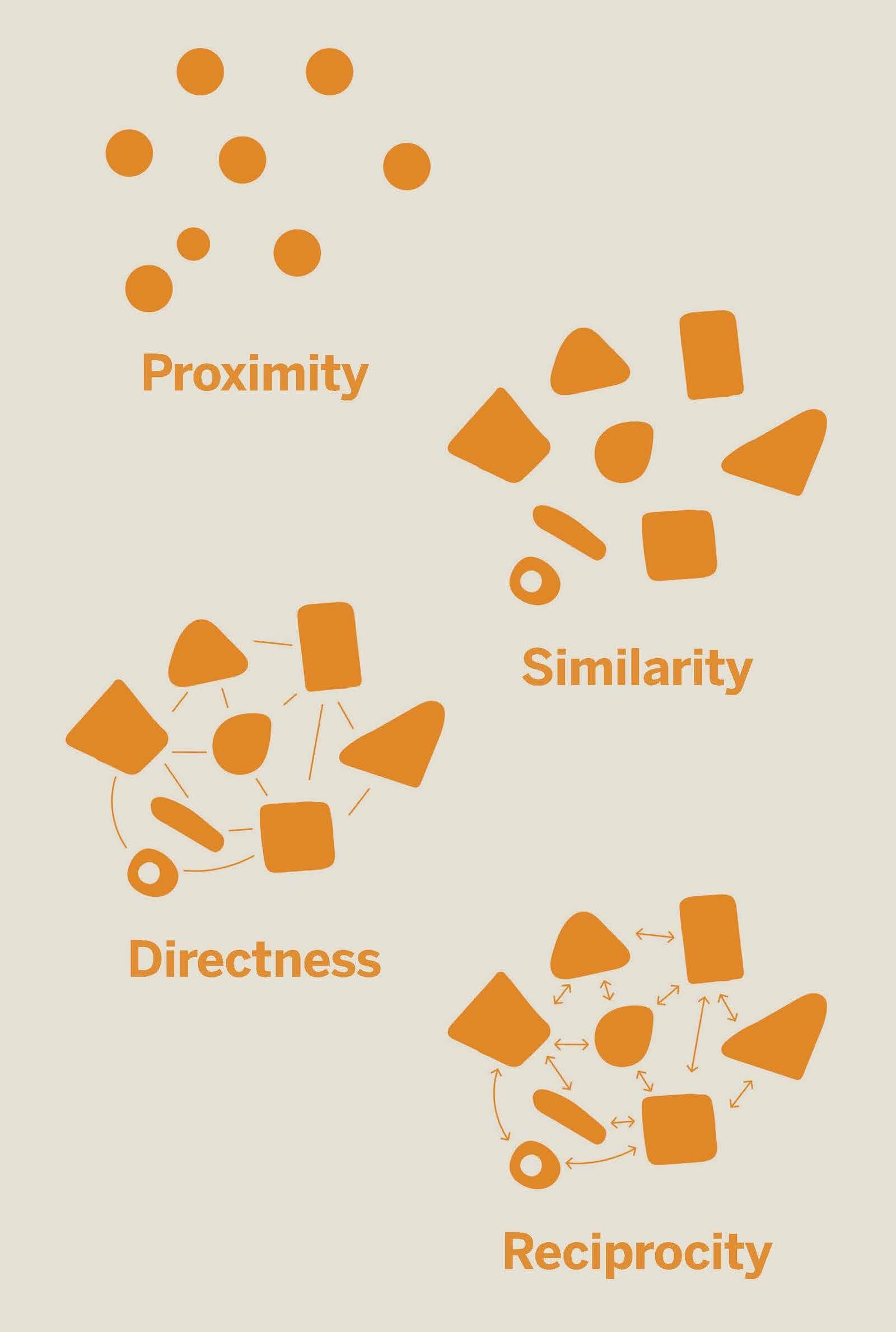

Trust is built on the knowledge of our commonalities and shared experiences. Conditions that build trust are proximity, directness, similarity, reciprocity, and disclosure. Trust can be domain-specific and falls within the limits of Dunbar’s Number on group size. The more we have in common, the easier it is to build trust. Overcoming our differences and avoiding misunderstandings or misinterpretations is the core challenge that can be bridged by being curious and open to looking for what we share rather than what’s different. Trust can be a powerful catalyst for communication and collaboration – it can make things that seem impossible, achievable.

Trust Creates Opportunity

People describe trusted relationships as the ones where the barriers we negotiate and struggle with seem to fall away, to be replaced by a flow of connection and certainty that makes everything seem possible. Stephen Covey in his book says: “Everything moves at the speed of trust.” He’s absolutely right. It allows us to rely on each other with less uncertainty and more independence, it improves our collaboration and communication, and it gives us hope to achieve things that would seem impossible to do alone.

Trust is at the core of every relationship we have. It informs many of our behaviors and beliefs. Trust is both forward-looking and rooted in our past experiences. When you trust someone or something, you give up a certain amount of control and make yourself vulnerable. You rely on the other side to do their part, to act with care and thoughtfulness by taking your intention and interests into consideration.

Trust is often intimate – that intimacy can make people feel uncomfortable. At the same time, it’s an essential part of our communication. Peter Block highlights this inherent challenge: “Of course we have something to get done by 3 o’clock today, but if we don’t spend some time talking about how we’re doing together, what we get done ain’t going to be worth anything.” It won’t be worth anything because if we don’t know and trust each other, we won’t be able to produce anything useful or new that has an impact.

Below, I will walk through a framework for understanding and creating trust, including ideas around the structure, the conditions that enable it, and how trust is built and sometimes broken.

Structure of Trust

When I think about trust, I see it as the connective tissue between people. We all have individual interests and experiences – they make us multi-faceted and our personalities prismatic. When we learn about each other’s interests and preferences or experience something together, a connection is formed. It’s quite a special feeling. I remember an instance when I met someone, and as soon as we discovered we both had a passion for sailing, something changed, and we could relate to each other through a shared language from the similar experiences we’ve had. Trust is made of many individual connections, linking us together through our commonalities and shared experiences. The stronger and more plentiful these links are, the more trust we have for each other. Because we connect to each other over particular interests and experiences, this trust is domain-specific. We might trust a colleague with a work-related task, but we might not entrust them with our cat. Over time, trust can expand into multiple domains.

Conditions for Trust

Proximity: Trust is built over time through repeated interactions. For any relationship to form, we need to be in each other’s spheres, meaning serendipitous opportunities need to arise that allow us to connect. Living in the same neighborhood, being friends of friends, attending the same book club, or being in the same school class all create the possibility to meet and then meet again. Those encounters allow us to get to learn about each other.

Directness: Trust develops most freely through direct, unmediated conversations. The more mediation there is, the longer it takes to build trust. A mediated conversation is everything from a video or voice calls, to an email or text message exchange. Unmediated conversations occur in person, allowing us to pick up subtle details such as tone of voice or gestures. Meeting on a regular basis in person is much more effective than a written message at the same frequency. The more unmediated or direct an encounter, the more we learn about each other. Our tone of voice, gestures, clothing, and mannerisms communicate something that’s hard to get across when you’re only reading someone’s words. I’ve experienced this in Slack conversations, where jokes get lost without a tone or facial expression, or from Zoom fatigue, when our brain spends a lot of processing power trying to form a cohesive idea from a low-grade image into what subtext is being communicated. This is also why it can take longer to build strong and trusted relationships in virtual communities.

Similarity: The more we have in common, the easier it is for us to build a connection. We have something to talk about, a similar interest, something we feel equally passionate or infuriated about, or an experience or a place that means something to us. We’ve both been there and know something about that experience. That’s why inside knowledge and jokes can be powerful connectors.

Disclosure: Trust is a function of how much we know about each other. The willingness to be open, share about ourselves, and be curious about others is key. The more honest and vulnerable we are about our past, attitudes, and feelings, the more opportunities we give the other person to learn about us and share back. This should be done slowly and over time, as it can be overwhelming.

Reciprocity: Trusted connections are a two-way street. Our counterpart will share if we do too, and they will only show up if we show up. The stronger trust becomes, the less transactional and more generous this reciprocity can be. What this idea means is: I will happily show up now, without keeping track or expecting you to show up right after, trusting that when I need you to show up, you will. It’s a form of social equity that over time becomes more plentiful and easier to share. We have a tendency to mimic each other’s behavior – sometimes this urge to fit in is subconscious and extreme.

This trust that we share and obtain over time undergoes several distinct stages: from meeting and finding common ground, to creating, testing, and finally trusting. It takes many repetitions in which trust is established, tried, and reinforced.

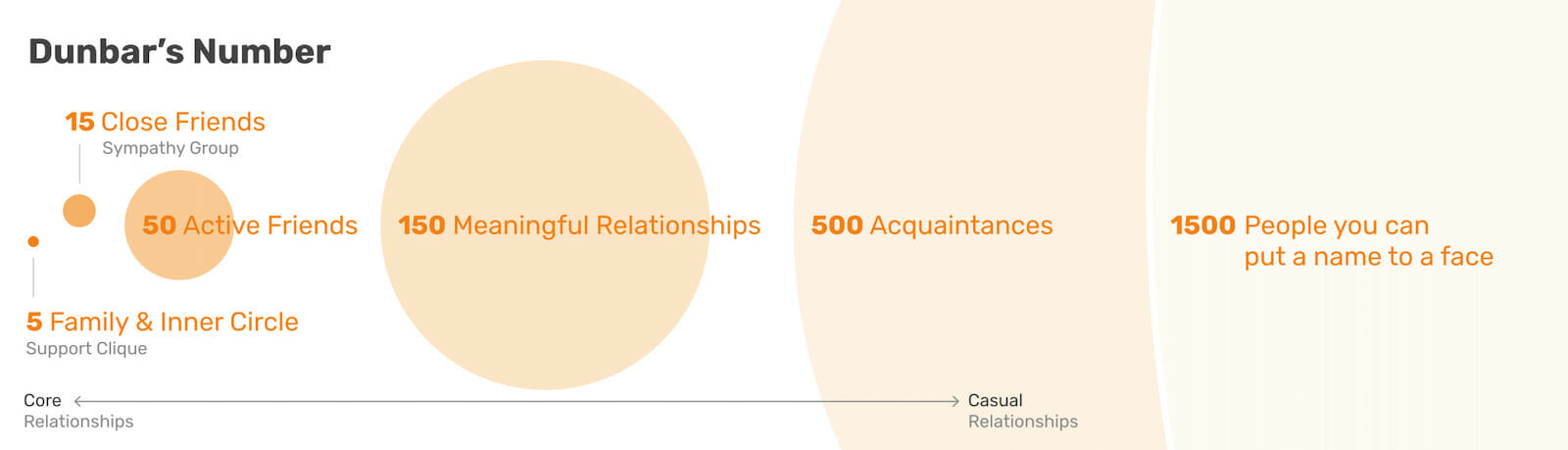

We also have varying degrees of trust with distinct groups of people. Dunbar’s Number, devised by British anthropologist Robin Dunbar, organizes our relationships into groups of 5, 15, 50, 150, 500, and 1500. We have the strongest sense of trust with our smallest and closest circle. Presumably, those are also the people we have spent the most time with, know the most about, and have experienced a lot with. As we move further out, we know less and less about them, and the levels of trust decline.

Ultimately, all of the above allows us to learn more about one another through conversations and experiences we have together. Trust is a function of how deep and wide the knowledge is that we have about each other. The more information we have, the more connections we can create, and that in turn will lead to a stronger sense of trust and more domains it can cover.

Building & Breaking Trust

Building trust is most difficult when there’s no immediate commonality apparent. We have our own perspectives, experiences, and expectations that we bring into every interaction. Spelling out everything that we’re thinking about or feeling in minute detail is hard, and what someone says or does can easily be misinterpreted or misunderstood. This creates dislike and distrust, which can be subconscious or based on prejudice from previous unrelated experiences.

We all have our differences, which make us complicated beings with contradictions and imperfections. They can make us better, but only if we can navigate them and build on them. Generally, we more readily trust people who are similar to us. Building trust with people who are different from us becomes easier when we can identify what we have in common.

How can we overcome our own biases, move past our differences, and relate to each other? Our curiosity and engagement with each other is crucial here. By asking questions and listening, we can find starting points and connections for a relationship.

We also need to give people a second chance or the benefit of the doubt. We might not be able to agree on all perspectives, but if we’re here to do something together, it’s helpful to focus on the bigger picture. We need to ask ourselves what we are trying to collectively achieve, to then make compromises that allow everyone to have their differences and distinctions. That’s obviously tough, because of our inherent biases toward conformity and consensus. In situations like that, I try to remind myself that my liberty ends where yours begins.

Trust that’s built over time through conversations and shared experiences creates a rich network of knowledge and connections between us, which in turn is a powerful catalyst for communication and collaboration. When trust is broken, rebuilding it often requires starting from scratch. As much as a strong connection builds trust, a broken connection creates mistrust and puts all other connections into question. Broken trust can degrade a relationship so much that it requires additional effort to mend it.