Design Museum Live: Visualizing Complex Data: COVID-19 & More Recap

Design Museum LIVE • July 2020

By Sara Magalio

In this July Design Museum Live event, we explored the world of data visualization, with a specific focus on how data surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved over this extremely mutable time. Paolo Ciuccarelli, the director and founder of the Center for Design at Northeastern University and Paul Kahn, a lecturer in experience design also at Northeastern, shared their expertise in the data design field and helped explain the trends that we are seeing in how COVID-19 data is being presented in the media and elsewhere.

Paolo began the event by explaining that when creating data visualizations, it is important to consider the fact that the phenomena behind the data can be very complex. While making interpretation of the data as simple as possible for the reader is always a goal, sometimes more complex visualization techniques are needed to take into account all of the moving parts behind the data.

Paolo warned against data presentation that fragments data for the sake of simplicity, without considering how these different components interact and inform trends in the data. He used a dashboard data visualization setup as an example of such compartmentalization, which can be helpful for organization, but detrimental to understanding the bigger picture. He noted that information designers must take a systemic view of the data to accomplish this end. Paolo prefers to think of people who work in data visualization as information architects, in the sense that these data analysts create, in the words of R. Saul Wurman, “systemic, structural, and orderly principles to make something work…the building of information structures that allow others to understand.”

Paolo also emphasized that the visualization of data should be viewed as a rhetorical system, but he acknowledged that this can seem paradoxical at first glance. “In a way this goes against this aura, this idea of data as being objective,” Paolo said. “But thanks to complex data, I think it’s quite understandable that data is a construction designed and produced by human beings, framed ethically, politically, socially, and technically, and so is data visualization.”

Since rhetoric is an inherent component of conveying data, inserting one’s bias is always a risk, so the designer needs to be aware of this risk and work to mitigate it, while also considering who is using the data, its context, and the purpose in the language behind the visualization. Specifically, it is critical to take into account the cultural distance between the data expert and the citizen interpreting the data, it’s important to especially take into account the aesthetic of the visualization to bridge the gap and help people engage with important, complex data that may not be familiar to them.

Paolo also clarified that different types of visualization are appropriate for different types of data, and that aggregating the data can be thought of as a process or journey, moving through analytical, narrative, and evocative interpretations of the numbers as the situation requires. He provided particularly emotive examples through sharing one of his students’ assignments— creating “Infopoesia,” or emotionally moving visualizations that help people to not only see the data, but feel the phenomena behind the data.

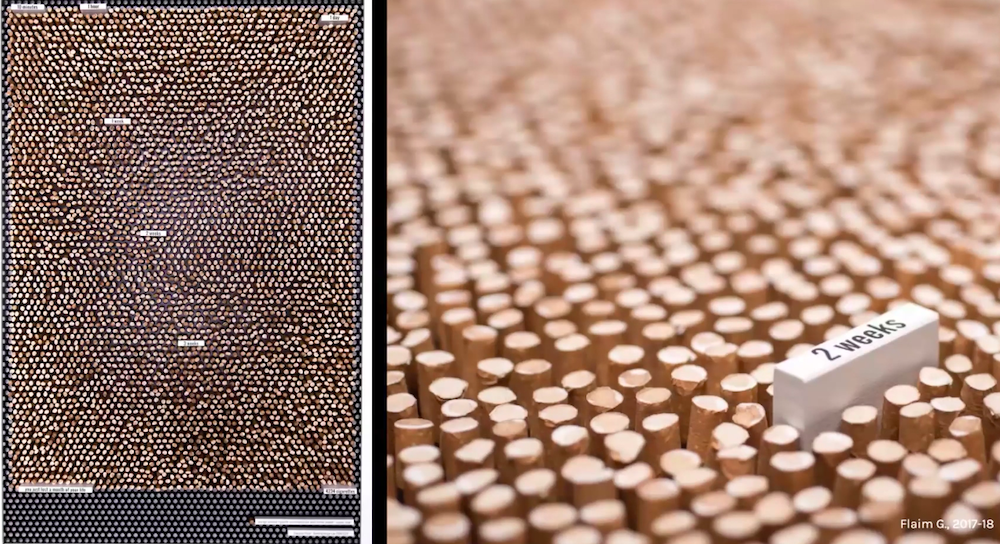

One example Paolo shared was a student who used cigarette butts pasted tightly together on a surface, with each butt representing a day of life lost by a smoker. Paolo said that the visceral impact of this design, including the overwhelming smell of the large accumulation of cigarette butts, helped to convey the ominous context of this data.

Paul Kahn took over in the second half of the presentation, and he focused more specifically on the evolution of COVID-19 data visualization. He shared a project that he, his students, and colleagues have been working on called COVIC–the COVID-19 Online Visualization Collection. This is an opportunistic collection of visualizations related to the pandemic. A significant part of what appears in the study includes online visualizations to explain aspects of the situation. In a few months, data visualization practitioners have created an astonishing number of representations all pointing to the same phenomenon—the COVID-19 pandemic—which we currently know very little about. The team is collecting and classifying representations to use for future research.

Paul noted that what is particularly interesting about this project is the enormous amount of data that can be collected about a very specific subject all over a relatively short period of time, and that his team can also look into the transition from print to digital representations of data, which is an ever accelerating evolution. He revealed that using different types of data presentations, such as bubble map charts versus choropleth maps, can impact how the viewer interprets the data, and that racing bar charts have become increasingly popular visualizations to show the changes in the number of cases and deaths over time.

Below are some data points that Paul shared from the COVIC project:

- About 50% of all the items collected in the study are from news media sources.

- Breaking down the types of visualizations being used, Paul’s team has found that there are more line charts than bar charts (907 v. 750 collected), and more bar charts than maps (750 v. 611). Illustrations are at the bottom of the pack, with only 284 examples cited so far.

- The team has collected samples from 50 countries, but 70% are from the United States and the UK, and about 80% of the items are in English.

- About 25% of the visualizations collected are “data update” examples, in that they are designed to load current numbers.

When looking at complex data that addresses a phenomenon that we have only preliminary knowledge of, such as the emergence of COVID-19, data visualizations can be extremely helpful for experts to share current trends and their findings with the general population. However, when this data is presented in a fragmented or convoluted way, the way that the data is interpreted when looking at the visualization can be drastically impacted. Also, an inundation of visualizations from numerous sources can be overwhelming for someone trying to understand the situation. It’s therefore important for the design architect creating the data visualization to consider the context of the data, the intended audience of the visualization, and the impact goal of the project, all to ensure that the end result is a visualization that both conveys the data clearly and elicits the intended response to the information presented.