Why Do We Need Community

How to design more powerful learning experiences

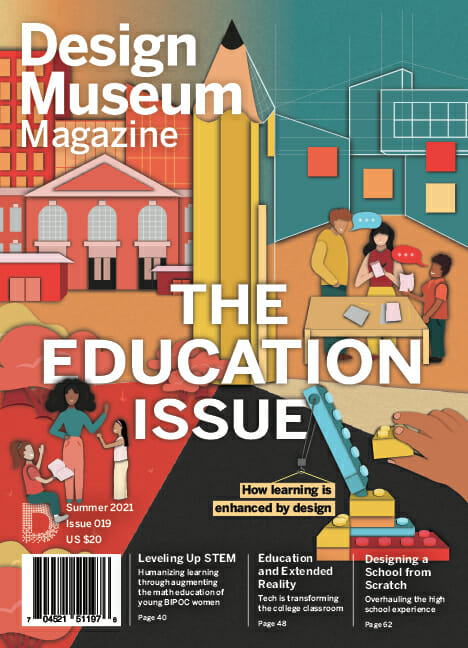

Photo by Unsplash

By Josh Kery and Mimi Shalf

High schools, research labs, and tech companies all define community differently. Who gets included in this definition often determines who gives input in the design of educational experiences. To what degree designers in education listen to their community of users and peers can change learners’ engagement and empowerment.

Focusing on the end product in education may disconnect your practice from pedagogy. Consider gamification, which has promised a fun way for educators and designers to engage and motivate learners. The trend popularized design elements like points, badges, and leaderboards before there was research evidence indicating whether or not they improved learning outcomes.

As common as gamified elements are in classrooms and in education technology (EdTech) today, education research is still unclear about which elements are impactful to student learning. This ambiguity, among others, should lead educators and designers to look more closely at how they choose and use learning theories and design patterns like those used to gamify classrooms.

Educators and designers might first consider who they are involving in their design process and how they are involving them. The community of users and designers is a powerful medium for crafting engaging educational experiences, and can lead to more informed, powerful, and inclusive learning environments. In this article, we will explore what it means to create a community through design and education by exploring a few instances where community and education have played off of each other to create a rich and full learning experience.

Background

Design-Based Research (DBR) could be a valuable touchpoint for those looking to rethink their designs’ connections to pedagogy and how to engage in the community of educational research that runs parallel to classroom education. It’s a methodology for conducting research in education, used by labs like the Embodied Design Research Laboratory at UC Berkeley. In DBR, designers iteratively create a design and test its impact on learners. These tests serve to evaluate and complexify the designers’ assumptions about how the design affects learners.

Dor Abrahamson, Director of the Embodied Design Research Laboratory, writes that the DBR process produces:

- a design artifact, with documentation of its starting context;

- new or changed learning theories that researchers use to explain their observations;

- and guidelines for other designers to create similar artifacts (also called a design framework or design heuristics) which “cohere,” according to Dor, with the above learning theories and design artifact.

These three results act as vehicles to pass information to the greater research community, so that others can separately consider the different aspects of a study, build off of its findings, and discover something new.

Bridging Research and Design Practice

While this describes how designer-re-searchers tap into their community of users and peers, it might seem distant from how designers in schools and companies can do the same.

We have come up with a pair of questions to prompt people to engage their own communities of peers and users in their design practice.

- How is knowledge shared in your community?

- How do you involve your community in the design process?

We will look at these questions through the lens of the community design center Cambridge D-Lab and the EdTech industry as practical examples of community engagement in design for education, with a focus on the lab’s signature participatory design structure.

Engaging Community in Other Design Practices

Cambridge Design Lab is a participatory design lab where students, families, educators, and school leaders can learn about design and work on self-identified challenges. Design coach and educator Angie UyHam founded the D-Lab in 2016 and continues to run it today with Khari Milner, Co-Director at the Cambridge Agenda for Children.

The D-Lab seeks to add design as another tool for its participants to utilize. Before identifying a challenge they’d like to design for, participants work together in groups to define a “design framework” for their project. Each group uses three images to represent the goals and qualities that will guide them during the process. We will be using the D-Lab as a model to help us think through our guiding questions.

Badges like these are a common reward for learners on EdTech platforms. Khan Academy, for example, awards them to students as they complete course content. The online learning platform emerged at the same time that gamification was becoming more popular in education research.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARY WOJNAR

How is knowledge shared in your community?

At the D-Lab, projects are documented in the form of storytelling and videos. Groups craft the story of their process to share with the community and save for later reference. Some projects have even gone on to be published or picked up by local university labs. Furthermore, some members who have finished their project will rejoin new cohorts and bring their knowledge of past projects with them. These exchanges have helped the D-Lab create an ecosystem of knowledge similar to that of a university research community. In both contexts, groups share results and build off of each other’s findings.

How do you involve your community in the design process?

The most remarkable thing about the Cambridge D-Lab is their use of participatory design, where students and teachers design the ideas that they will use themselves. In this way, the designers and target users belong to the same community. Projects become deeply embedded in the environment where the designers are working, and the designers may be more wary of theories and design heuristics that might push archaic assumptions onto their work. To elaborate more on the D-Lab’s participatory design process, we met with Elijah Lee Robinson, Sharon Lozada, and Jeff Goldenson, who are a part of an ongoing D-Lab group, Down with Design.

Case Study: Down with Design gathers timely feedback and empowers its designers to make change

“What’s special about this project is it’s led by students,” Elijah told us. Elijah is a designer in Down with Design and was a sophomore at Cambridge Public Schools at the time this article was written. He joins other students, parents, and teachers to work on Down with Design every week. The group is addressing student mental health by organizing a series of outdoor events where students can socialize, play games, and make art and music. Down with Design is a working example of how the D-Lab engages its target community as designers to solve issues in the school system. With Elijah and his peers working as designers, the group taps directly into their own network to research issues at CPS and collect feedback. The parents and teachers in Down with Design play a supporting role in this process. “I’m always trying to figure out how to make sure we’re not getting in their way,” noted Sharon Lozada, a teacher at CPS and member of the D-Lab.

At the D-Lab, images were used to represent the guiding principles of a group’s design work. Pictured: An example of Angie’s design framework: eyes (awareness + learning), head (interpret + brainstorm), and hands (prototype + improve).

Centering youth is one of the many needs recognized as a barrier to equity among Cambridge teens. In 2019, the district released a report from its Building Equity Bridges project, which highlights how the school system needs to better center youth and educators of color in its schools and distribute decision-making power more equitably among the voices of families. “The main point from the report was feedback—some people were being heard and some weren’t,” noted Sharon. In response to this, Down with Design is centering the voice of its students. Setting up a way for students to talk to administrators and board members and be heard is crucial to bringing their vision for change into reality.

As CPS students, the designers in Down with Design have the clearest insights into the key issues for their classmates. With the project, Sharon reported, “Students are creating events that fill the void of what isn’t available to them from the school.” As the coronavirus continues to place a social and emotional burden on students, it was clear to Elijah and his group that they wanted to help their peers take care of their mental health. As a group, Down with Design drafted this question to pursue: “How might we create opportunities with students so they can connect with peers and caring adults, so they feel nurtured and supported?”

The Down with Design group is also best equipped to prototype answers to this question with their peers. Elijah is realistic about how difficult it is to motivate his classmates to attend an outdoor event. Down with Design offered prize money to teens at its first event because, as Elijah said, “We wanted them to gain from it,” and, “We’re playing into how teenagers are.” Similarly, the designers know the best indicators of success in their solution. Down with Design mediated feedback from attendees at their first event with a collaborative writing board, getting many comments the group said will inspire future events.

The best indicator of success to Down with Design, however, is seeing their community grow. Elijah told us he felt this most when his group organized an extra meeting to recruit more participants. To his surprise, his peers took the time to come in. “It was nice to see that people cared, to see them show up and make an effort together,” he said. Designer and CPS parent Jeff Goldenson sees this as an accomplishment in how students perceive community service. “Our young people have the desire to make change,” he remarked. “We just need to frame it in a way that resonates with them and inspires them to do more and more.” While it’s no surprise that the designers in Down with Design care about the outcomes of their work, the intrinsic motivation to improve the community that the group has inspired is a good note for educators. The ways we can listen to our learners—from participatory design to simple user feedback—might further invest them in their own education.

Cambridge Public Schools students waited for the start of Down with Design’s first gathering at Starlight Square in March

Despite Down with Design’s success, the D-Lab is continuously looking for more ways to invite this collaboration and community formation. An idea for a group typically spreads by word of mouth, according to Sharon, and there is a need for more robust institutions that can connect people in the community and jumpstart design groups like this. As Jeff noted, “If there were more ways to give, there would be a lot more people giving.”

Many designers beyond the D-Lab, including those in equity-based design and DBR, are seeing similar benefits to participatory design. They recognize the value of involving end users as designers in their community, forming teams with more accurate understandings of the needs of the design’s target audience.

Case Study: EdTech’s focus on scalability has led them away from community

Let us take a step back and look at another sector of the growing education community: EdTech. EdTech involves the use of technology such as hardware or software to facilitate learning, and usually refers to companies that build this technology.

To learn a little bit more about EdTech, we talked to Parth Shah and Elizabeth Lin, who both have extensive experience working in the industry. Parth is currently an Experiential Learning Manager at the online technical education program Lambda School, but he previously worked on curriculum at Codecademy and GitHub. Elizabeth is the Founding Designer at the homeschool platform Primer, but she previously worked as a designer at Khan Academy and as a Design Learning Manager at Lambda School. Through their experience and expertise with educational technology, Parth and Elizabeth offered thoughtful and objective opinions on the industry.

For Parth, EdTech’s biggest impact lies in its ability to bring content to the masses. He pointed to Lambda School as an example: as an entirely remote bootcamp, Lambda School’s students come from all over the world and hold a very diverse array of backgrounds. In addition, EdTech has made educational content more widely available to people. Learning resources are easily shareable thanks to digital technology, and it is much easier to make curriculum, content, and classes free online. In other words, educational technology has the potential to have a global impact. As a result, for better or for worse, many EdTech companies are obsessed with creating a product that can grow bigger, better, and reach as many people as possible.

Parth and Elizabeth both agree that EdTech’s prioritization of the scalability of a product may not necessarily be the most beneficial route for the industry or the educational experiences they create. “Good education doesn’t always scale and doesn’t necessarily have to,” noted Elizabeth. EdTech companies struggle with creating space for communities that can scale with their product and user base. “It’s hard to develop a sense of community with EdTech products,” she mentioned. Parth described community, structure, and mentorship as the three main pillars of good and successful educational experiences. At Lambda School, he focuses on getting the students to get to know each other first, so that they can help each other learn without depending on the instructor. Having a community is a vital part of the experience, because it empowers learners to work together and independently take their education beyond the platform. “Feeling engaged with each other is really important,” Parth remarked.

The problem with EdTech, Parth pointed out, is that companies invest in the community aspect—arguably the most important aspect—too little and too late. In the race to make a product that will scale easily to reach the most people possible, the problem of how all of these people can connect with each other is easily overlooked. By ignoring communities, companies are withholding a precious resource from their users: the huge and diverse group of people they have managed to reach with their product.

Parth and Elizabeth believe that great educational experiences won’t always scale well, and at the end of the day, may not even need to scale at all. While Cambridge D-Lab works in a different area of education with slightly different goals and resources, it doesn’t hurt to take a few notes from a group where the community is baked into the entire design process. Some EdTech platforms, like Primer, have already started making the move to more inclusive and community-focused design processes. For Elizabeth, participatory design and community are especially important for products like Primer, which are focused on teachers. “Teachers are experts in the classroom and bringing them into the design process is how you can come up with the best ideas,” she noted, adding, “Personally, I love co-designing sessions with students as well, because they always have wild ideas for how to make education more fun!”

Final Thoughts

Maybe it is time to redefine what it means to successfully scale a project or product. Perhaps impact isn’t necessarily just somebody using a product or platform, but inspiring them to go work on what they are interested in. We’ve seen from Cambridge D-Lab that scalability isn’t necessary to create significant impact; rather, engaging with the community and empowering them to make change can have a deeper and more meaningful influence in people’s lives.

The Cambridge D-Lab, design-based research, and educational technology all hold a similar goal: to make education more interesting, accessible, and exciting for everybody. Communication with the education community has proven to be crucial to achieving this goal. Design-based research neatly packages findings to share with the wider research community, while EdTech uses technology to reach more and more people every day. The D-Lab brings people together into a collaborative learning environment through the power of participatory design. As new innovations in educational design develop, communities will guide the future of education to be a more inclusive and enriching experience for all.