If we’re not being thoughtful about who we’re designing for, the context of their individual and collective stories that brought us to this point, and the ultimate people-centered outcome that we’re striving for, then I’m not sure we’re engaged in more than a design exercise.

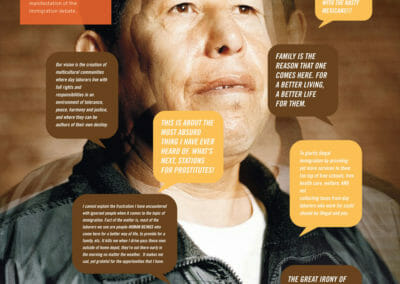

Photo by Ryan Lash

Liz Ogbu is the founder and principal of Studio O, a multidisciplinary design practice working at the intersection of racial and spatial justice. A designer, urbanist, educator, and activist, Liz is an expert on sustainable design and spatial innovation in unjust urban environments. Her involvement and education in design have been comprehensive and wide-ranging. She studied architecture at Wellesley for her undergraduate degree and earned a master’s in architecture from the Graduate School of Design at Harvard. She was also among the first group of innovators-in-residence at IDEO.org, the sister nonprofit of international design giant IDEO. Liz has also been an Aspen Ideas Scholar and TEDWomen Speaker.

She has written for and been featured in publications such as The New York Times, Bloomberg (formerly The Atlantic), CityLab, the Journal of Urban Design. Liz’s writings center the stories of historically marginalized communities and how they are affected by the spaces in which they live. In her 2022 article in U.S. News and World Report titled “Reckoning and Repair in America’s Cities,” Liz explains, “Space has often been used in this country as a system of control and exclusion. The American landscape is physically shaped by historical injustices dating back to its earliest days as a country, when land was stolen from and used to warehouse Indigenous people and plantations were platforms for the enslavement and dehumanization of Black people.”

Space has often been used in this country as a system of control and exclusion.

What if gentrification was about healing communities instead of displacing them?

Liz Ogbu is an architect, challenging gentrification through spatial justice. In Liz’s TED Talk, “What if gentrification was about healing communities instead of displacing them?”, she asks for designers, government leaders, and real estate developers to stop equating progress with the erasure of culture and to “make a commitment to build people’s capacity to stay in their homes, to stay in their communities, to stay where they feel whole.”

Video produced by TED

PROJECT HIGHLIGHT: THE DAY LABOR STATION

Advocacy by Design

Liz employs the power of design to work with communities in need to catalyze healing and foster environments that support people’s capacity to thrive. When working on a project, Liz immerses herself in the historical context of the community and the physical space where the organization is working. She tries to forge genuine human connections with the people she works with and to build trust by focusing on cultivating relationships and avoiding transactional interactions. For example, as a project for Public Architecture, where Liz served as Director of Design, she led the design and development of The Day Labor Station, an innovative design and advocacy campaign working with day laborers across the country seeking to address critical issues of space, dignity, and community. At the time, over 110,000 people looked for labor work each day in the US. Their role in the informal economy often forces them to occupy spaces meant for other uses. The Day Labor Station was designed to be adaptable and capable of being deployed in various locations to provide a sheltered space for the day laborers to wait for work and community resources such as a meeting space, classroom, and garden. Though not built, the project served as an effective advocacy tool for the National Day Laborer Organizing Network and continues to be a much-cited project within the architectural community. The Day Labor Station is just one of many projects that highlight Liz’s creative approach to community-centered design.

The Decision-Making Table

“I try to educate myself on what the historical context of a place is. Who has had access and who hasn’t. Who has had power and who doesn’t. And who is seated at the decision-making table and who isn’t and could benefit from me leveraging my own power, privilege, and creative agency to help get them a seat at that table,” Liz said. “I also spend a lot of time in conversation with all project stakeholders, particularly those who have been most impacted. I don’t rely on community meetings as the only platforms for engagement, but rather seek out invitations to people’s homes, places of business, or wherever else they feel comfortable.”

Physical and Emotional Healing

“When I talk about providing space, I’m talking about both physical space and emotional space,” Liz said. “We do physical healing through the design and emotional healing by listening fully. Even if it makes us feel uncomfortable. Even if we feel we have nothing to do with the pain. We have a responsibility to stand in the presence of it. It’s not just about a financial or physical investment; we must make an emotional investment as well.”