Interview with Suenn Ho

The Garden of Surging Waves in Astoria, Oregon, is a community space that uses storytelling to highlight the history of Chinese heritage in Astoria. Designing the garden was a harrowing eight-year undertaking. Throughout the process of negotiating a location change, finding funding, and organizing local Chinese elders, designer Suenn Ho was determined to create a community space worthy of Astoria’s rich history. The result is a contemplative space driven by custom-made art and eclectic architecture.

Listen

Suenn Ho Interview Transcription

Suenn: I’m Suenn Ho, and I am an urban designer. I was born in Boston when my parents were at graduate school. I grew up in Hong Kong and after high school, I came back to Massachusetts for college. I met my husband in architecture school in New York City, and we are now business partners.

J.R.: One of the most beautiful aspects of the Garden of Surging Waves are the stories. Before we dive into the storytelling elements of the Garden, I wanted to ask you about the story behind the project.

Suenn: It’s a strange story. I had never done anything like Garden of Surging Waves. When the City of Astoria asked me to design and build a commemorative garden to tell the story of early Chinese immigrants’ contribution to the building and development of the city, I thought, why a classical Chinese garden? And they said, “because that seems to be the thing to do if you want to commemorate Chinese contributions.”

I did a little bit of research on the city, which is the oldest U.S. settlement west of the Rockies. The research told me about the richness of the Chinese population and their work. They built the jetties, they built the sea walls, and they built a sewer system. Of course, there were thousands of them. They were working in the salmon canneries in the mid-1880s. And all this has nothing to do with the classical Chinese garden style or stories because classical Chinese gardens were designed for the elite. But Astoria was built by workers. Even today, the locals like to say, “We ain’t quaint,” because Astoria really believes in the working class. I gained a little more insight into what they are about and told them they don’t have the ingredients to make a classical Chinese garden successful. But they have a lot more to showcase, and we focused on changing that story to be about them.

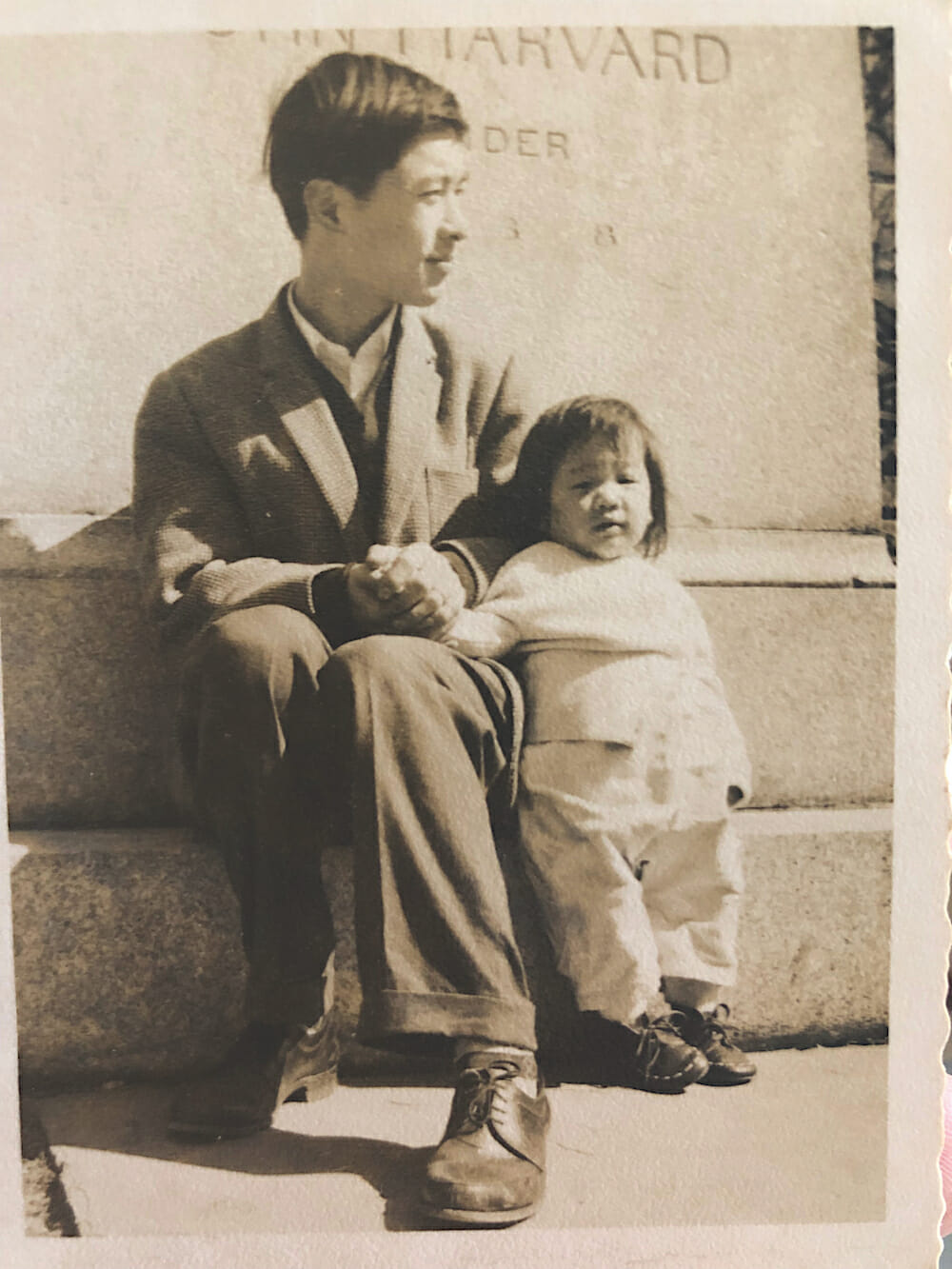

Suenn Ho with her father, Tao Ho, at Harvard in 1962.

J.R.: Tell me just a little bit about urban design. What do they do?

Suenn: My definition of an urban designer is someone who creates an environment that is based on the surrounding built forms. You are integral in a built setting. Then you add or subtract to it to enhance the place and give meaning and give quality to the environment for the people who live and work there.

Suenn with Astoria’s Mayor at the grand opening of Garden of Surging Waves in 2014.

Garden of Surging Waves Moon Gate. Moon Gates act as physical and spiritual entryways into traditional Chinese gardens.

J.R.: Can you talk about what you mean by “how to do it right?” How you were able to explain “how to do it right?” to the municipality that you were working with?

Suenn: “How to do it right?” Maybe I will focus on the Garden of Surging Waves. First, I did not want it to be a reconciliatory really sad story. I wanted to pay homage to the people before us, the people sitting on the project committee, and the elders. Only sixty or so Chinese live in Astoria today, as supposed to the thousands before. They are holding onto stories, history, and their relationship with the place they are so connected to.

So, how to do it right when the city wants to build a classical Chinese garden? To do that right, I had to clarify to the city that I wasn’t qualified to design a classical Chinese garden. I needed to do something that I knew could be authentic, honest, and respectful. Generations of families were sitting on the same Chinese Park committee. A grandfather and granddaughter. They all sat there staring at me, asking, Okay, if we don’t do classical Chinese garden, what are we gonna do?” How do we tell their stories? They still wanted a pagoda and a moon gate. These features are typical in a classical Chinese garden, yet this was a modern project. How do we do that without making it almost like a fake theme park?

To do it right for this project, you have to understand not just the history and the culture of the Chinese, but you also have to look at what Astoria is. It’s a river town located at the mouth of the mighty Columbia River. The marine climate is extremely hostile to any material.

The city introduced the project to me by saying that they didn’t have any money and I couldn’t use anything that would rely on extensive maintenance. That meant to me that we needed materials that would last, not just last, but could be celebrated for aging. Can we say, “You know what? This thing is rusty, and that is beautiful!” This material has a patina and drips onto the ground and makes stains. We celebrate it. It’s like the elders sitting in front of us who are aging. You want to honor them. And I think for this project, to do it right, I needed to capture that Chinese value so they could relate. That’s what I mean by doing it right.

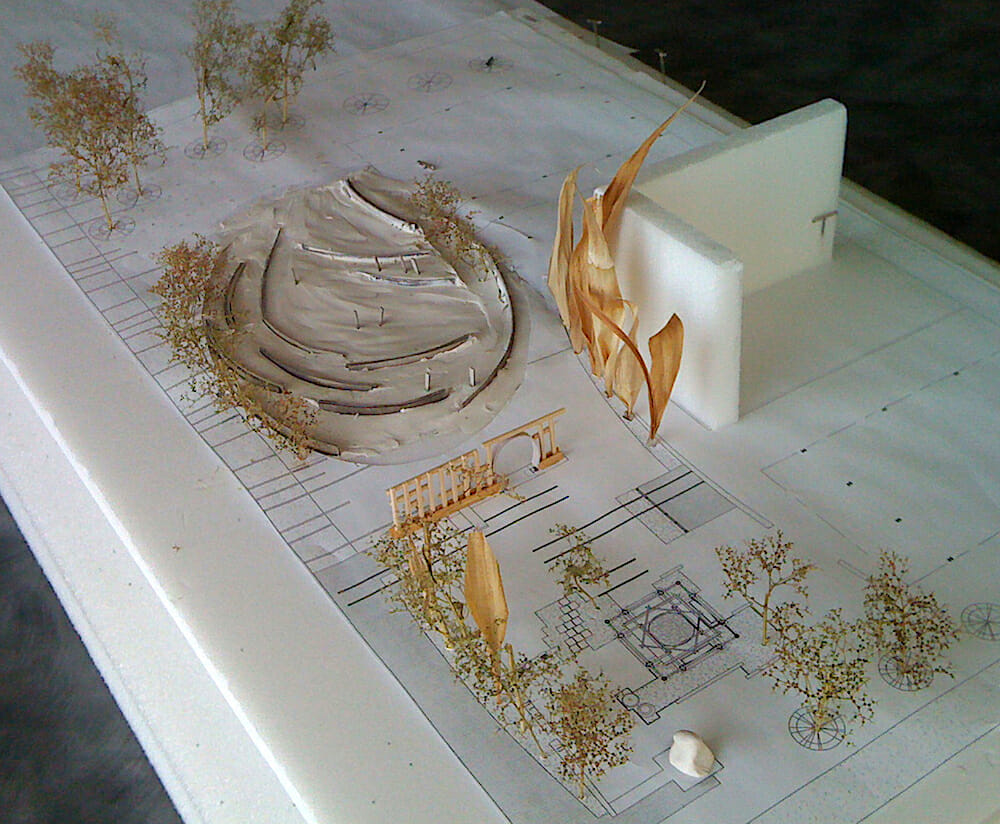

Model of Garden of Surging Waves.

J.R.: For other designers listening to this, was there a moment where you felt incredibly overwhelmed by this project? And how did you move through that?

Suenn: Yes, it’s incredibly overwhelming. The sense of responsibility goes back to “doing it right.” But I think the same thing whenever I approach any client who values my strategy or thinking. I appreciate the fact that this project, the committee, the Chinese families, and the city had such open-mindedness. The elders and the younger generation believed this project needed to be done.

The city has a little bit of funding. And the site was originally a small, 5,000-square-foot lot by the river walk. To make things even more complicated, the site was already occupied by an installation by the late Robert Murase, a very famous Pacific Northwest Japanese-American landscape architect. He did what he did, and the city hated it. The city wanted me to do something on top of his work to honor the Chinese. And, you know, the Chinese and Japanese have such a sad history, and I just didn’t know what to do. How can I respect Robert Murase, the elders, and the Chinese families all in this location? Then the mayor called me and said, “Don’t worry about it. We demolished it, so it’s a clean slate for you.” I thought, “Oh my gosh, this is horrible, but you’ve got to move on, right?” So I thought, deep in my heart, I needed to do something to at least honor Robert Murase. There was a little line of “Murase’s landscape rock” left at the site. Conceptually, I repurposed it to symbolize the river walls that were built by the Chinese. There was also an old concrete platform by the edge of the river walk that might have functioned as a loading platform. I persuaded the city not to demolish it, as it cost money to demolish or remove anything from the site. I thought, “let’s keep what is still there and work with it.” And that platform, jutting over the water, was then conceptualized as the Platform of Heritage. It became a little bit of the history of the site that was then interpreted as the start of a nine-square grid; a design principal in traditional Chinese architecture and planning.

The other overwhelming moment was when the city liked the design of the project so much that they said, “Let’s move the Garden of Surging Waves to an empty parking lot in front of City Hall and call it Astoria’s Bicentennial Legacy Project.” All of a sudden, I had this sense of like a little toddler having my diaper fall off my butt. It’s like, what <laugh>, who am I to be given this incredible, honorable opportunity? And I have absolutely no portfolio to show I know how to do it. And yet sitting in front of me are all the people looking at me with starry eyes, saying, “Suenn, whatever you decide, we will support you.” I thought this is unreal. <Laugh>, I better do this right, <laugh>.

So, to go back to your question about how I moved this project forward. I really did it in bite sizes. Whatever we do, we need to have a sense of vision that captures the feelings, right? It doesn’t have to be a palace, and it doesn’t have to be all built-in gold. We needed to capture something that Astorians can reflect upon that you say, “Yes, this is us.” The “bite-size” notion comes from after you articulate what is grand in terms of capturing the feelings, then you break the process up into bite-sized steps. One step after another and each is very digestible for the city and the Chinese Parks Committee to understand and lead to their decisions. Every step will then be thoughtful and grounded in influencing the next step.

What choices give the client a sense of engagement and input? As a designer, I like to draw. I will provide them with loose sketch vignettes and say, “This is something I came up with, but it’s informed by the site and what’s already there. The design is then informed by research of the place, the community’s history, and an understanding of regional materials.” You dial it down to a very conceptual level, to the point where they understand that everything you do has a reason with intention and relevancy.

Grandma said that dad was so sick on the boat from China that he would have been fed to the fish if he had died. Now a seafood lab is named after him for the fish feed that he and his team developed.

J.R.: How did quotes become a visual element of Garden?

Suenn: I wanted to tell the stories of the Chinese contribution to the building of Astoria. Yet…the voices from the Chinese community just were not there in any archival documents.

I asked the elders to provide me with some quotes about themselves. None of them wanted to say anything. To them, there was nothing to talk about. It’s just hardship. It’s ugly. Then I asked their children—my generation of helpers, members, and collaborators—and they said, “Dad and Mom never told us anything. And we didn’t think of asking them.” And then, I panicked. I thought, “Okay, this is not good. I need to have their voices.” So I said, “Okay, elders, don’t talk about yourself. Tell me about your parents, your grandparents, your families.” I didn’t know that would open up the floodgates. That’s why all these quotes coming through so beautifully. Here are a few, if I may read them.

“My grandfather brought home salmon cheeks, a delicacy to the Chinese but a waste to the cannery owners.”

“After arriving from China, my dad took a year to save enough money working in San Francisco. And he then walked to Astoria.”

“My mom butchered the frog, put the skin over little peach cans, and let it dry to make drums.”

“My mother graduated with a college degree, but Chinese women seldom had job opportunities. So she settled for a housekeeping offer.”

“Grandma said that dad was so sick on the boat from China that he would have been fed to the fish if he had died. Now a seafood lab is named after him for the fish feed that he and his team developed.”

“He prepared clocks with great skills and built cuckoo clocks with everyday materials.”

These are just a few stories that differ from newspaper clippings or census data. These stories are relatable between generations. It’s like when you are on a bus or walking on the street and overhear someone talking. The story didn’t have a beginning or end, but you capture a little bit of what’s been heard, and it gives you a moment to ponder—what is that? That pondering moment is what I would like people to experience. Time to ponder and be self-reflective. That’s how the quotes came to be on the story screen, which begins the experience when you pass through the gate and enter the Garden.

J.R.: Did all of the quotes come from Astorians? Are they mixed in with Confucius quotes and other references?

Suenn: The story screen features quotes from the elders and some of their children. One of them stated, “without this project, I would have never heard these stories from my dad.” She’s in her late fifties, and this was the first time she heard her dad’s story about his parents. And I thought, “well, that’s great because everybody can relate to the project.” So these are the quotes of so-called modern-day Chinese community members. I don’t want us frozen in time, only talking about the ugliest moments. Chinese history has thousands and thousands of years of civilization, literature, science, arts, and craft medicine.

Hardship comes into every community and every race. The Chinese experienced hardships, but you must understand the difficulties in the context of where this culture came from. What are values in their society that we all share and pass on from generation to generation?

So three bronze scrolls horizontally intersect the vertical story screen, including quotes from Confucius, Lao Tzu, and a 13th-century nursery rhyme. They’re all in Chinese and English. Hoping that allows one’s awareness of the fact that we, as a community, tie to something beyond us that brought us here today with that sense of pride, value, and sensibility.

People argued that the vertical screen would drip rusty steel water onto the bronze below and have this chemical interaction, causing it to rust. Isn’t that the life of an immigrant? Isn’t that why they came to a different place, a new home that picks up a few different things? That sums up the awareness that we live in a society that focuses on perfection. It has to be flawless. It has to be stainless. And yet, I think we forgot to look at grandma’s wrinkles and the gray hair we eventually all have. Don’t be shy about showing them off because, like one old friend told me, “yeah, I can always gain more experience. But I have also brought in a lot of experience. I shouldn’t be judged based on what I don’t know, but my work should be valued and honored based on what I already have and can share.” This is what I would like the Garden to achieve.

Here is a sampling of many invaluable collaborators who were critical in making the GSW a reality:

The Duncan Law Family, The David Lum Family, The Calvin Brown Family, The Allen Wong Family, The Bertha Saiget Family, The Willis Van Dusen Family, The Norman Locke Family, The Anne Barbey Family, The Arlene Schnitzer Family, The Art DeMuro Family, The Jerry Lee Family, The John Flynn Family, The Chinese Park Committee, Senator Betsey Johnson, Mayor Van Dusen and City of Astoria staff and City Council. Artisans: Juno Lachman, Doug Metz, Lynn Adamo, and the inspiring Huo Bao Zhu!

J.R. Uretsky

Exhibitions Manager, CoDesign Collaborative

About the Interviewer

J.R. Uretsky (she|they) is an artist, performer, musician, and art curator living in Providence, Rhode Island. Uretsky has over fifteen years of experience organizing, designing, and installing exhibitions. Uretsky worked as the curator at the New Bedford Art Museum, where she exhibited Pete Souza (Chief Official White House Photographer for President Barack Obama) and Academy Award-winning (Black Panther, 2019) costume designer Ruth E. Carter.