Debra Latour

Occupational Therapy Educator • Prosthetics Designer & Advocate

Dr. Debra Latour is an occupational therapist, inventor of prosthetic technology, and professor at Western New England University.

Photo by Nancy Carbonaro

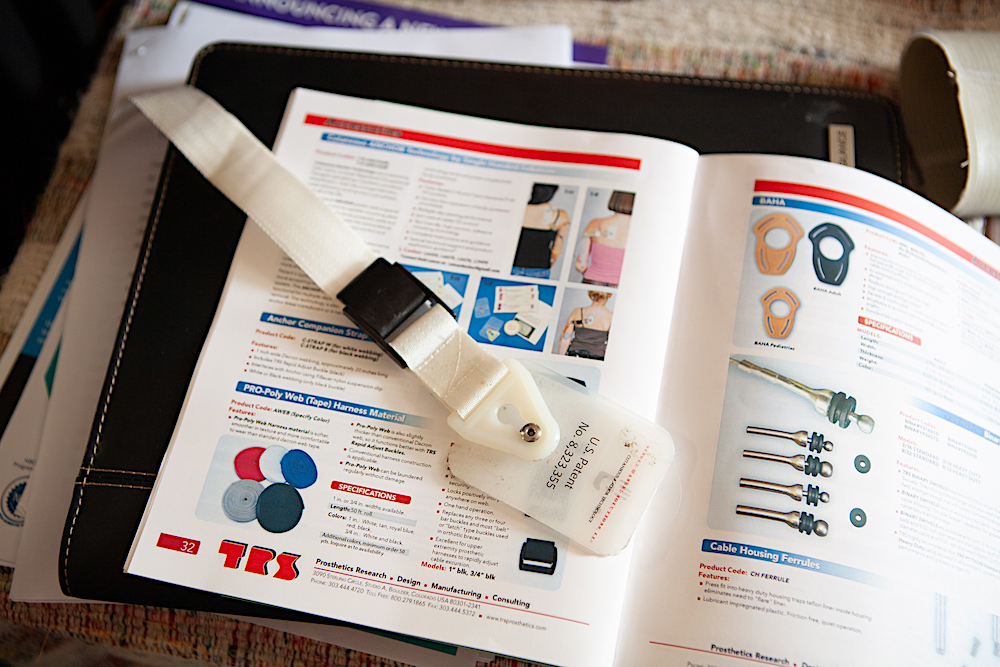

The first prototypes I made were with scraps of materials at Shriners Hospitals for Children. I started with splinting materials and bought overall buckles at the fabric store. I would mess around with ribbons and I would sew in webbing and shorter harnesses. Within a couple months I came up with something that I thought was a good prototype and I started wearing it.

Dr. Debra Latour’s prosthetic innovations have dramatically improved the lives of countless people around the world, including her own. Her multifaceted career and passion for accessibility design have encompassed many roles, including therapist, educator, product designer, and advocate. Debra’s experience within these fields is both professional and personal. Born with a congenital upper limb difference, she was the youngest person in the US to use a prosthetic arm. Frustration with rudimentary technology and discomfort of wearing her prosthesis throughout her life eventually led Debra to creative problem solving and the establishment of a new patent improving prosthetic design.

My personal mission has not been to make a million dollars, but to make a million differences.

Debra was a voracious reader with an early interest in science and teaching. After completing a BS in occupational therapy at Tufts University, Debra has since pursued a Masters of Education in advanced OT at Springfield College and a doctorate from A.T. Still University in Kirksville, Missouri. She began her career as a registered occupational therapist at Tufts-New England’s Biomedical Engineering Center in Boston, and she has joined academia as an assistant professor of occupational therapy at Western New England University.

Debra is the inventor of prosthetic technology including the patented Cutaneous Anchor Technology and the TAB (patent-pending). Developed during her time as a therapist at Shriners Hospital for Children, she gifted the patent to the hospital once gaining support for her creation. However, unable to gain necessary industry interest and facing exorbitant licensing fees through the process with Shriners, she proposed manufacturing and marketing the system herself. Debra took business classes and filed a company name under Single-Handed Solutions in 2011. The patent, finalized in 2012, is currently on its third iteration and being distributed in the US, Europe, and Canada.

As the owner and founder of Single-Handed Solutions, Debra strives to improve prosthetic technology with new patented prostheses and through consulting with medical professionals, manufacturers, and patients. Debra also works with the Amputee Coalition of America, where she calls for more research to improve health care and insurance coverage of prostheses with the goal of impacting public policy.

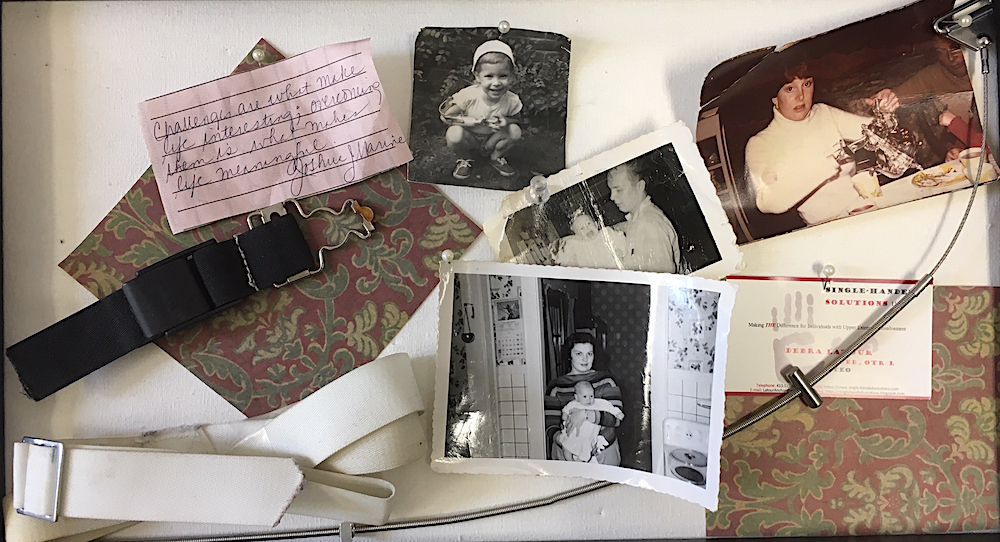

PErsonal History

Photo courtesy of Debra Latour

Youngest Recipient

Debra was born in the 1950s in West Springfield, MA with a congenital upper limb difference. Her family was determined that she not be held back, and began seeking care at Shriners Hospital for Children when she was just a few months old. Initially turning her away for being too young, they eventually agreed to make Debra a test case. At 14 months old, she became the youngest person in the US to be fitted with a prosthetic arm (the standard at the time was age five). As Debra recalls, “this was at a time when a lot of people believed children who were different should be hidden away.”

Embracing the Inevitable

As a child, Debra found the harness for her prosthesis to be uncomfortable. It would pull on her clothing and make her feel encumbered, which often led her to hide her device. She didn’t realize its full importance until witnessing her father pull the arm out of their burning furnace after it was accidentally tossed in with the garbage. She soon learned to incorporate a split-hook prosthesis into her life, realizing how it allowed her to engage with the world and learn tasks with her peers.

“My parents believed so strongly in the importance of my success,” Debra said. “My prosthesis was a sign of hope and something they fought for. They thought that if I did well with it, that it would also change prosthetic intervention for children in the future. And that is exactly what happened. As an occupational therapist years later, I have fit and trained children as young as 4 months old with prosthetic technology. I’m proud of the impact of my parents and my heritage with that.”

Artifacts from Debra Latour’s childhood

Photo courtesy of Debra Latour

Photo courtesy of Debra Latour

Looking to Prominent Women in Science

“I remember reading about Marie Curie and being so in awe that a woman could be a scientist,” Debra said. “I had never heard of occupational therapy, but I thought about science and teaching. I was on an accelerated track and I made it into a program with the top students in 6th grade. Females in the 60’s were not encouraged to be much beyond teachers, nurses, or maybe to go into service professions, and I remember it was so novel to me then to realize that these other girls are interested in science too!”

A Teaching Moment

Debra was sometimes bullied and penalized for not having two hands. In 1971, her 9th grade teacher would humiliate Debra in front of the class by forcing her to alphabetize papers while counting down from 10 and pounding on her desk. He said her “physical handicaps” affected her mental ability, which was agreed upon by her guidance counselor at the time. Aside from arranging new teachers and counselors for Debra, her mother told her to make the experience into a teaching moment for everyone. On the last day of school, Debra shook the teacher’s hand with her prosthesis in front of the whole class, thanking him for the learning experience.

“One of my champions was my new guidance counselor, Mr. Laufer,” Debra said. I am to this day indebted to him. He listened to me, and asked me what I wanted to be in the future, which at the time was a journalist. He said, ‘I just can’t help to think you have something to offer in the helping professions.’ I spent the summer going on college visits and talking to people, I investigated social work and vocational counseling, and the more I read into it, I kept coming across occupational therapy, which I realized was mixing art and science, and helping people. I said, ‘are you kidding me?! I want to do that!’”

Forging her Own Path

“Part of my required experience at Tufts University/Boston School of Occupational Therapy was in field work, both in mental health and in physical medicine and rehabilitation,” Debra said. “I opted for a third, because of course I wanted to do something nontraditional. I was interested in assistive technology and biomedical engineering. My work at the Tufts Biomedical Engineering Center was my first experience in research, design, and engineering, combining all of that to devise things and environments so people could perform. They ended up creating a position for me, and I worked there a few years.”

Photo by Nancy Carbonaro

Photo courtesy of Debra Latour

Finding the Right Fit

Over the years, Debra has worn many different professional hats. She spent years in a discouraging role advising on accessibility for a state institution, where she felt her ideas were not being valued or implemented. She then gained experience in creative, adaptive worksites at South Shore Industries, before getting married and moving to Seattle. Working as a school-based therapist after her second daughter was born on the west coast, Debra chose a similar career path once moving back to western MA after her divorce, where it was also her focus to raise two happy and well-rounded children. When she saw an opening at Shriners Hospital for a therapist position, Debra jumped at the opportunity, calling it a “cathartic experience” that also allowed her to pursue an advanced practice master’s degree in occupational therapy, because of their continuing education benefits.

While working as a therapist at Shriners, Debra developed the Cutaneous Anchor Technology, a new system for upper-limb prosthetic anchoring that attaches to and relies on the wearer’s shoulder blade to control the prosthesis. This design eliminates traditional, uncomfortable harness systems that often deter people from using body-powered prosthetic devices.

Debra left Shriners in 2012 to start her own business and consult with major prosthetics companies like Handspring, TRS Prosthetics, and Liberating Technologies—organizations she met when speaking at conferences about the Cutaneous Anchor Technology system. Aside from teaching in the doctorate program at WNEU, she has since completed a Doctorate in post-professional occupational therapy with a focus on program development, evaluation, and policy. Her thesis resulted in a recent article, called Unlimbited Wellness, published in the Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics.

“When I started doing research, it blew my mind that the harness has been attributed to 90% of people’s abandonment, and nothing had been done,” Debra said. “I have a voice, and as an aging adult I know that one of the greatest legacies and impacts I can make is to make a difference for others. My personal mission has not been to make a million dollars, but to make a million differences. In this next chapter, I would like to show people that we as occupational therapists can impact public policy as well as populations.”