A Unifying Vision

By Candace Brooks, Senior Design Researcher, Agncy

Four years ago, I started working with Agncy, a Boston-based firm that uses design as a tool to reduce structural and systemic inequities in communities across the country. The concept of co-design is the centerpiece of our design and research work, and it allows us to create a process that is community-centered, rather than designer-centered.

As a designer, finding Agncy was a godsend! I’d been searching for an organization where design was used as a tool to address our country’s social problems. At Agncy, I get to couple my interest in understanding why people do the things they do, with the design processes I learned as a student at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) and the human-centered lens I learned at the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). Agncy is a place where all of my skills combine into a toolbox to deconstruct the foundational problems I see in our country. The co-design process pushes me to think harder about what service design means when working with communities, particularly when our clients are government agencies. Too often in government, the people in power are separated from the people who will experience their decisions. They are often not from the communities they serve, and have either never worked directly with those communities or haven’t in some time, as they moved their way up in rank.

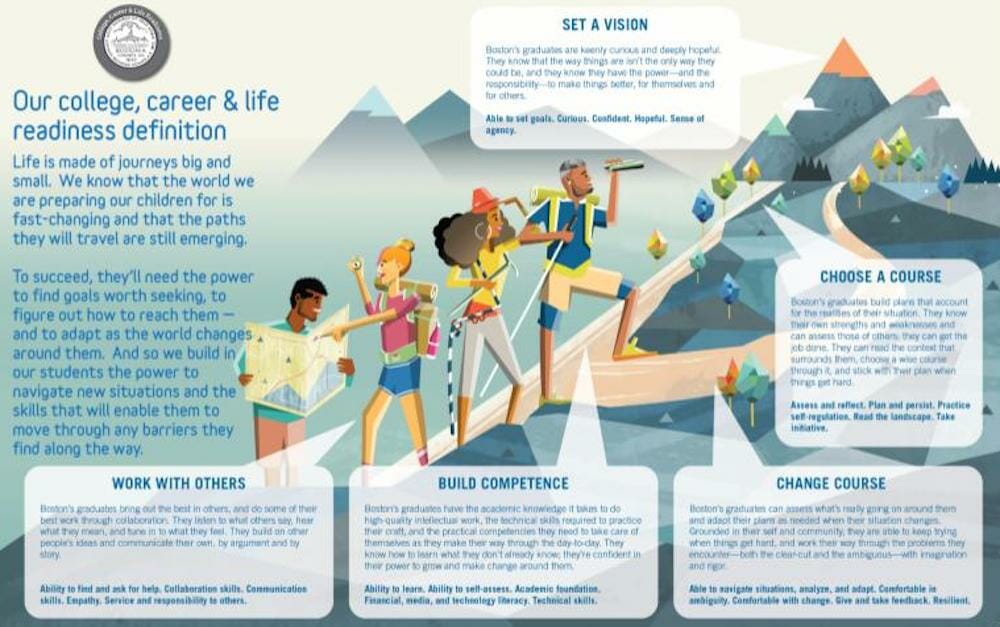

In 2017, Agncy partnered with Boston Public Schools (BPS) to design Boston’s “College, Career & Life Readiness Definition (CCLR).” At the time, graduation requirements and grading standards for students from BPS, charter schools, parochial schools, and other non-profit organizations differed throughout the city’s ecosystem. The goal of the CCLR was to create a common understanding for the district and the broader Boston community, which would describe the life skills and knowledge every BPS graduate should have. This tool would then be used throughout the education ecosystem to gauge how well students were being prepared for their futures. The original CCLR design was co-created over five work sessions by BPS school leaders, teachers, community members, and district partners. In 2021, BPS school leaders and their partners wanted to re-examine the CCLR to reflect current contexts that graduates encounter, since so much had changed during the intervening five years. Once again, they invited Agncy to facilitate the co-design process. Our expectation, alongside that of the BPS high school superintendents, was to approach the changes by simply updating the existing CCLR. On a rainy day in late June 2021, approximately 30-40 school leaders convened in Essex, MA for a retreat. It was one of Agncy’s first in-person meetings since the pandemic started, and the Agncy team was excited to work together with our partners in real life again. Many of the school leaders in the room that day were different from the ones on the original co-design team. School leadership had shifted with promotions and turnover, and these new leaders wanted to see their voices reflected in the updated version. In fact, they told us they wanted to “blow it up and start from scratch.” The updated College, Career, and Life Readiness Definition, renamed the “Vision of the Graduate,” would be co-designed by a multitude of stakeholders—including school leaders, teachers, district partners, and community and business leaders—plus: it would feature more voices from students, parents, and caregivers.

Boston Public School’s College, Career and Life Readiness definition (2017)

When I reflect on the experience of redesigning the CCLR, I’m reminded of Van Phillips, the talent behind the Flex-Foot. As a student at MassArt, I attended the 1998 International Design Conference in Aspen, CO with a group of students from industrial design, architecture, fashion, and graphic design. The conference theme that year was sports, and we met academics and design practitioners from around the world who designed everything from sporting equipment and gear, to accessible national parks, to the logo and branding for the 2000 Sydney Olympics. One of the stand-out presentations that year was on the design and development of the Flex-Foot.

As a college student in 1976, Van Phillips had a water skiing accident that severed his left leg and completely upended his otherwise active lifestyle. For the first 10 years after his accident, Phillips lived with prosthetic devices prescribed by his doctors. Most were crude and somewhat clunky, fashioned out of wood made slightly more comfortable with layers of foam rubber but still contributed to Phillips being in near constant pain. Rather than succumbing to his circumstances, Phillips put on his designer and inventor hat and sought out to develop a new prosthetic device. After a summer internship in San Francisco followed by enrollment in a master’s program at Northwestern University, he was determined to create a prosthesis that would allow active people like himself to enjoy sports and the outdoors as much as anyone else. Phillips believed that “invention is almost always just arranging things in a new way.”(1) His early prosthetic designs were made to replicate a human leg and foot wearing a shoe. He self-tested every prototype—using them for running, hiking, playing tennis, you name it—but eventually, each one failed. He kept trying to recreate the leg he had lost, until he realized he had the opportunity to design something better.

This was a paradigm shift. Phillips began to work towards creating a device that would make the conditions and context of his new reality work for him, not against him. He didn’t need a prosthesis that would look like or even function the same as a human leg. He could instead create something that was built for speed, agility, and comfort. Finally, Phillips turned to nature for inspiration. Using biomimicry of the fastest land mammal on the planet, he studied how the leg of a cheetah works as a spring: compressing and flexing to propel the animal forward while running. This model from nature was the perfect mechanism, and—combined with materials that were stronger and lighter—Phillips created a device that could store and transfer energy in a way similar to a cheetah’s leg. This paradigm shift is reflected in our work at Agncy. We don’t want to recreate what already exists, and we don’t want to change people from being who they are when they’re at their best. Rather, we seek to change the system and break free of conditional restraints that require individuals to accept re-designs which do little but uphold the status quo.

The current draft of the Boston Public School’s Voice of the Graduate (2022)

I imagine Phillips was grateful for the wood prosthetic his doctors gave him, but it didn’t allow him to live his best life in his revised, current reality. Similarly, while the 2021 school leaders saw the value of the original CCLR, they knew it didn’t speak to the best their students could be, nor did it acknowledge the current realities facing their graduates outside of school. In those original designs, both Phillips and the school leaders were finding a way to color within the predetermined lines. But just as Phillips wasn’t content to live with limited mobility, the 2021 school leaders made it clear that they wouldn’t settle for a tszuj-ed up version of the old College, Career & Life Readiness Definition. Seeing new possibilities allowed Phillips to let go of a design that merely mimicked or replaced his lost leg, and it got him to consider a form that delivered the results he was actually looking for. The school leaders followed a similar path.

During the 2021 redesign, we found that the students were really excited to add their point of view to the Vision. They were particularly adamant about including elements to address diversity. They genuinely valued collaborating with and learning from people of diverse perspectives, races, ethnicities, and sexual identities. They wanted to highlight how their generation was ahead of those prior in this regard, which wasn’t something their teachers and school leaders had previously recognized. The students also felt that developing relationships, adapting to change, and the ways their classroom lessons connected to their lives outside of school needed to be included in the revised Vision. At the same time, the teachers felt their unique expertise in student skill development in the face of current social pressures should also be recognized. One teacher at the Jeremiah E. Burke High School noted how the new Vision helped her see the ways her teaching needed to change. For this teacher, the responsibility of educating young people was one that would impact the next seven generations of her students’ futures. (2) She was excited by the possibilities the revised Vision opened up for her.

Ultimately, the 2021 Vision of a Graduate was designed by the very stakeholders who would themselves use it as a tool. Dr. Lindsa McIntyre, a Secondary School Superintendent at Boston Public Schools and a dedicated partner in this work describes the impact of the Vision and how it works in concert with other initiatives this way, The Vision of The Graduate will speak to the access and opportunity provided to each and every Boston Public School student while simultaneously outlining the multiple pathways the journey to MassCore success and completion allows. The iterative process of crafting the Vision of the Graduate included multiple stakeholders; students, teachers, school leaders, administrators and community members all contributing to an understanding of the qualities of a Boston Public School graduate. The vision has been pressure tested on Innovation Pathways, Advanced Placement Course, International Baccalaureate Pathways, Early College and Dual Enrollment, as well as Career and Technical Education. All roads along this journey will lead to a progressive academic experience that enables:

- A common set of objectives across the system

- Opportunities to align work across a system that can be disparate and siloed

- Ways to connect to post-secondary stakeholders and opportunities

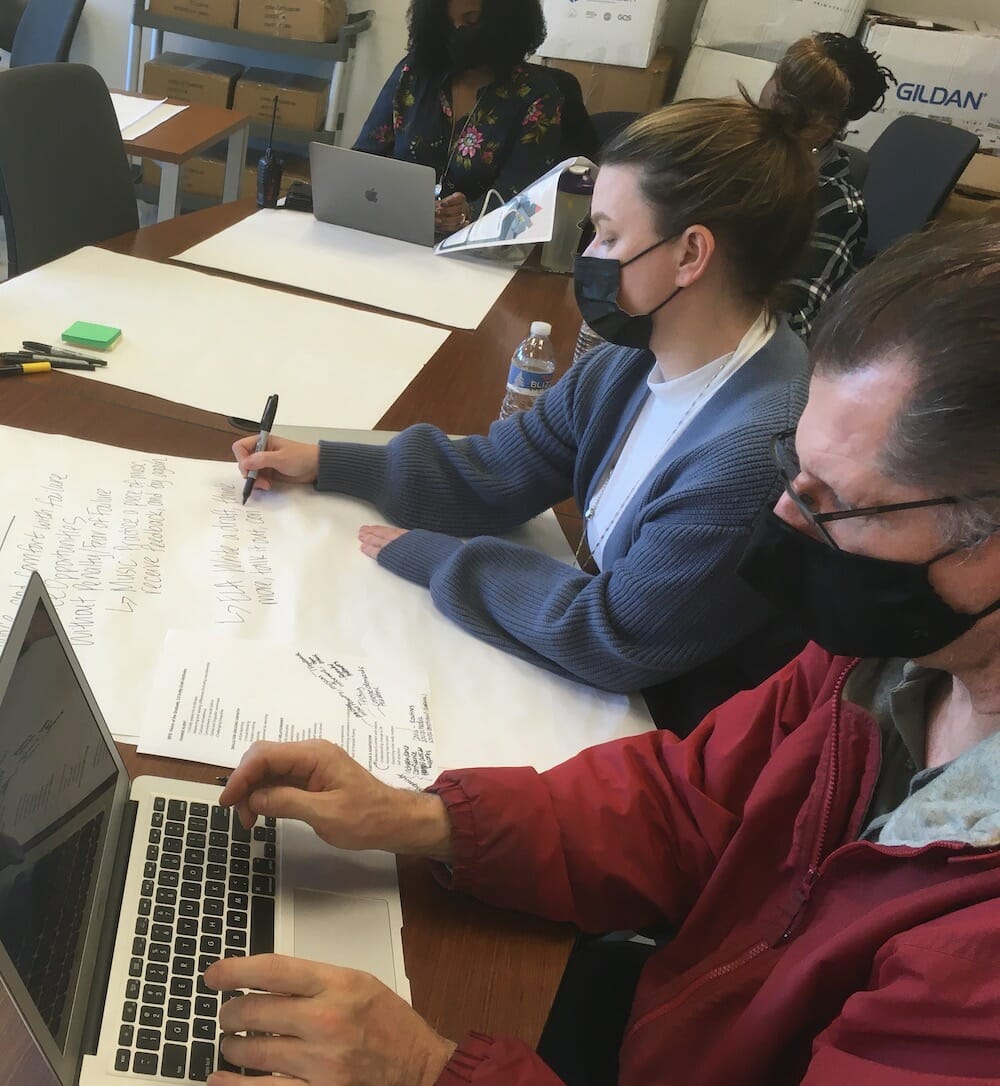

Teachers at the John D. O’Bryant High School hard at work sharing their feedback on the Voice of the Graduate draft.

While it was challenging to co-create something that articulated the voices of so many distinct individuals, our hard work was worth it and will serve as a unifying tool for the city. Antoniya Marinova, Director of Education to Career at The Boston Foundation and Interim Executive Director at the Boston Opportunity Agenda puts it this way:

In Boston, constructing a vision of a graduate has gathered a lot of important momentum over the past year. We are fortunate that in our city, there are a ton of initiatives and programs that seek to prepare our high school graduates for a successful future. A collective vision of what our students should know and be able to do to be prepared or that future—in other words, a vision of a graduate—can provide a unifying roadmap that anchors these multiple district-, school-, and partner-led efforts and align them in the service of the same North Star goal.

I don’t think I’ll ever forget that rainy day when the agenda for our retreat with the BPS superintendents and school leaders seemingly fell apart right before our eyes. I remember exchanging glances with my colleague thinking, “What the hell do we do now?” I knew we could throw together a draft based on what we already understood about the school district, and then share it back to them for feedback— but that would not uphold the values we have at Agncy. If we as a company aspire to honor community members through co-design, then having our planned agenda go off course was the perfect opportunity to roll up our sleeves, join forces with our client, and do the work.

Ultimately, people will have the power to opt in or out of the solutions we help design, and no one wants to join in on a system that only recreates something which is broken. I’m more convinced than ever that when design focuses on what a community is truly capable of, better outcomes are possible. This approach is not only more equitable, it also recognizes and centers expertise, and it redistributes power. Design shouldn’t be about creating a better mousetrap, and it’s not about being the only person in the room with a good idea. For me, design is about creating opportunities for everyone to find solutions to the systemic inequities we all face. Even when implemented with folks in large governmental bureaucracies, individuals can envision their own futures, rather than having power-holders attempt to define it for them. And if there are lines, the final image will be that much more beautiful when we color outside of them.

1. Davidson, Martha. “Innovative Lives: Artificial Parts: Van Phillips.” Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. Smithsonian Institution, 20 Apr. 2020. https://invention.si.edu/innovative-lives-artificial-parts-van-phillips

2. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/seventh-generation-principle