Rethinking Boston’s Storied Planning Agency

Human-Centered Design in City Hall

Images courtesy of Continuum

By Jon Campbell, SVP, Experience & Service Design, EPAM Continuum and Ken Gordon, Principal Communications Specialist, EPAM Continuum

If you wandered into a community meeting in Boston last summer, you’d be invited to a table to sign in on a sheet of paper. The paper was also where you were supposed to write down your question for the meeting. Glancing around, you might ask, “How do I know if I have a question when the meeting hasn’t even started yet?”

We dropped by a community meeting to observe how the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) — the City of Boston’s storied planning and development agency — got on with the public.

The meeting began. In walked the real estate developers, easily identified by their suits. Among them moved the suit-and-tied Project Manager from the BRA. The suits took the stage, the meeting began, and we understood that this was going to be a spirited gathering. When you have a small collection of attendees, all thinking that they represent other groups, jammed into a space with two Spanish-speaking translators and a dance class in progress in the next room with young kids leaping around while a piano bangs away, you don’t have a community meeting as much as community cacophony.

The BRA Project Manager did what he could to encourage dialogue between the developers and residents. The developers clicked through a PowerPoint deck, but it didn’t connect with the crowd. We walked out of the meeting thinking that the BRA had a problem. Civic engagement in Boston was clearly active, but it wasn’t very productive.

What Is the BRA?

The Boston Redevelopment Authority. Doesn’t quite trip off the tongue, does it? Perhaps more problematic is the more-often-used but less-formal acronym, BRA.

But naming issues were hardly the only, or most important, challenge for the planning agency. The BRA has been around since 1957. Originally, the Massachusetts General Laws — chapter 121B, section 4 to be specific — empowered the BRA to take over the work of the Boston Housing Authority, and it soon added non-public housing to its portfolio. In 1960, the BRA and the City Planning Board became one. The organization has ballooned over the years. It now oversees 500 properties, employs more than 200 people, and brings in a lot of cash ($59 million in revenue in 2014). The BRA’s money derives from real estate, grants, and government funding. An entity that has been historically opaque in its operations, the very idea of the BRA didn’t sit well with many citizens and community groups in Boston. The BRA’s brand was muddied early on by its urban renewal initiatives. The chronic unpopularity of the BRA was pe rhaps best summed up in a 2013 Boston Magazine article which suggested: “Nothing does more to kill a conversation with architects or developers around here than asking them about their dealings with the BRA.”

One such controversy swirled around the BRA’s infamous urban renewal project in Boston’s West End. Back in the 1950s, 41 acres in the West End were declared “blighted areas” and “slums” and bulldozed to the ground, kicking thousands of people out of their homes. This is precisely the kind of history that led many to believe that the BRA was siding more with developers and less — much less — with the citizens of Boston.

Many people, from many neighborhoods, looked on the BRA with suspicion. “I’m trying to believe them, but I think there’s just a deep well of cynicism about all this,” said Lydia Lowe, co-director of the Chinese Progressive Association in Chinatown, to the Boston Globe. “I need to see some real structural changes.”

When Marty Walsh became Mayor of Boston in 2014, he decided to make the previously obscure workings of the BRA public. He ordered two audits of the agency: one from KPMG (financial) and one from McKinsey & Co (operational). The KPMG audit discovered $4.3 million in unpaid lease payments, no eviction policy, and a compliance department that was ineffectual. The Globe reported that the audit by McKinsey revealed “a dysfunctional bureaucracy” without a comprehensive list of properties, enormous employee morale problems, wanting vision in the BRA’s leadership, and a culture McKinsey described as “hierarchical, siloed, and not transparent.” Following those audits, the Mayor called the BRA “a mess.”

Things had to change. The BRA created an action plan and focused on such items as prioritizing their proactive planning activities, elevating real estate management, and professionalizing their organizational management.

A Complex Design Challenge

Enter Continuum — we’re a global innovation design firm headquartered in Boston’s Innovation District. Our relationship with the BRA began with an especially honest request for proposals that read, in part:

By acknowledging past mistakes, opening the Agency’s doors and books to outside review through two independent operational reviews, introducing new ways for the community to meaningfully engage in planning and development review processes, and making a concerted attempt to better explain sensitive decisions to the public, the BRA is working to instill a reform-minded attitude in all that it does.

We saw that the BRA needed a partner who understood what real culture change required, and we gladly accepted the challenge. We have years of experience helping organizations transform themselves by placing their stakeholders at the center, and we were thrilled at the chance to apply this experience to our own city. When the RFP said, “In order to continue to effectively partner with the community to shape a more prosperous, resilient and vibrant city for all, the Agency must establish an identity that is reflective of the organizational reforms underway and that inspires greater trust and confidence from the people it serves, the residents and community members of Boston,” we replied: “Sign us up!”

We relished the fact that the BRA sought to remake itself — a difficult task that screamed out for better means of public engagement, internal operations, transparency, and for human-centered design. We needed to rebrand the BRA, that was obvious. But we also needed to help employees embrace this brand and drive change from the inside out. And ultimately we would need to sketch out the right strategy and create the proper instruments to allow internal teams to implement the strategy for long-term change.

Starting in late May 2016, we immersed ourselves in this complex, challenging project, and over the course of 14 weeks, we went to work on a new organizational strategy and brand identity.

Embedding Ourselves

How to begin? We needed to see the BRA and its stakeholders in context. Ethnography is a major element of our design process, and embedding ourselves in real-world situations is the best way to find the right design.

So we attended community meetings at the Boston Common Hotel in Back Bay. The development initiative under public review at that time was a mixed-use, transit-oriented development of approximately 1.26 million square feet.

BRA community meetings were usually during the day, sometimes in the morning, sometimes in the afternoon. It’s hard to make it to a meeting if you work 9-to-5. Most of the attendees at the meetings we attended were older, often people who bought brownstones in the Back Bay in the 60s. Some attendees could be characterized as idealistic Baby Boomers who started their families in Boston when things were affordable. A lot has changed since then. In general, the attendees didn’t represent the diverse population of Boston, and we couldn’t help but wonder whether involving a broader population in Boston’s planning and development process might yield different results.

We completely embedded ourselves within the BRA by immediately forming a cross-functional core team of BRA employees, to cut down on the strategic message loss as these new ideas were passed from person to person and department to department. The core team met twice a week to share insights with us — allowing us to learn directly from their expertise. We also created a larger, extended team, to which we provided updates and received feedback through participatory workshops. We conducted stakeholder interviews across BRA departments, and assembled a steering team, which was populated by six of the mayor’s direct reports. This gave us visibility across many relevant city departments.

The first four weeks were all about listening and learning. We spoke with every type of stakeholder we could imagine, including citizen advisory groups, advocacy groups, and individual residents — a mix of people with pro-, anti-, and neutral opinions on the BRA. We spoke with media to get their perspective — way off the record. We spoke with architects and developers. We spoke with a variety of people from other city departments: streets, parks, neighborhood development, and more. We talked with a lot of people — and recorded every insight.

Designing for and in Public

We decided to make our process publicly visible by documenting it all — learning themes, insights, implications, and more — on the web.

Why did we go public? We believe transparency builds trust, and our understanding was that the impenetrable screen surrounding BRA activities was one of the things that so angered and alienated the people of Boston. We realized that replacing the current curtain with a transparent one — or, better yet, to ditch the curtain entirely — was a way to allow trust into the equation. The website made every single step in the BRA project public as a means of saying: this is a new, different sort of organization, one with nothing to hide and everything to share.

The BRA had never done anything like this before — they’d never put out a real-time account of their work. We convinced them, and ourselves, that it would send a message that the BRA’s planning and development activities were in the best interests of Bostonians. Launching the website at the beginning of this project would serve as an important precedent for all forthcoming actions on the agency’s part.

On the site, readers were encouraged to comment on our work, which helped inform the direction of the project. We shared project information in a clear manner instead of the often-used city-speak jargon that many Boston residents find confusing. This kind of open-air design was thrilling and a little scary, but in the end it was the right thing to do for this public design project.

Name & Organization Change

To make a big change, you need to think big. So we created an overarching strategy for the BRA around driving inclusivity in a changing city while encouraging engagement among all citizens. We focused on planning and emphasized a big-picture view to promote the future success of Boston. This thinking led to the new BRA vision — with four key pillars to activate the strategy — as well as a new brand identity.

The Boston Redevelopment Authority needed a new name. Working with the organization, we identified three criteria for the moniker. The new name had to: be functional, as opposed to whimsical; highlight the city of Boston; and prominently feature the idea of “planning.”

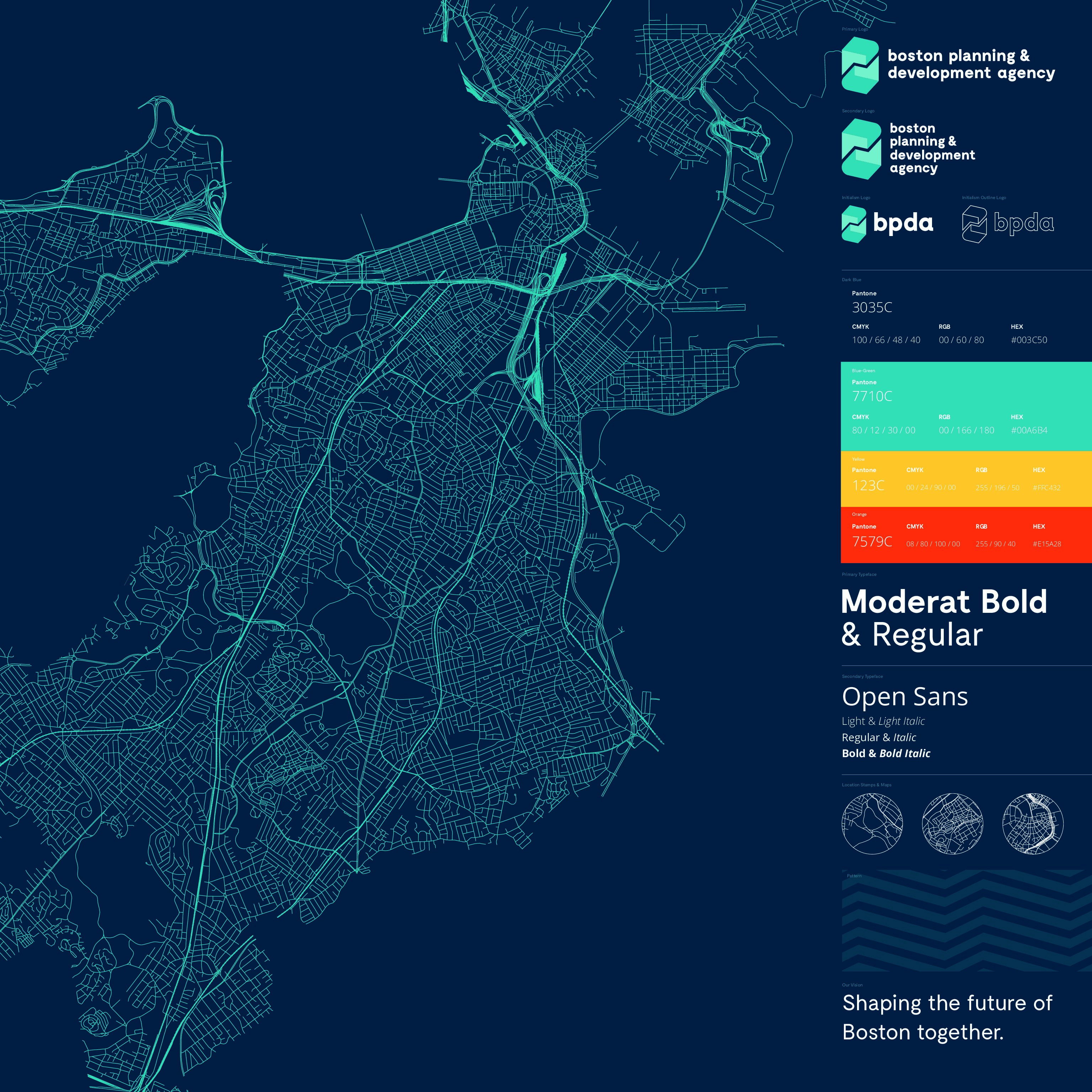

To decide on a name, we explored more than a dozen ideas and winnowed those down to a handful. Planning was a very important element of the BRA and it had to be part of the name. We also wanted to drop the word “authority” which has a number of negative connotations. After much strenuous debate, we suggested that the organization call itself the Boston Planning & Development Agency, or BPDA, to better identify what the agency is and what it does.

That was just one element of the brand work. We believed the brand should be people-centric, optimistic, rigorous, insightful, and adaptable.

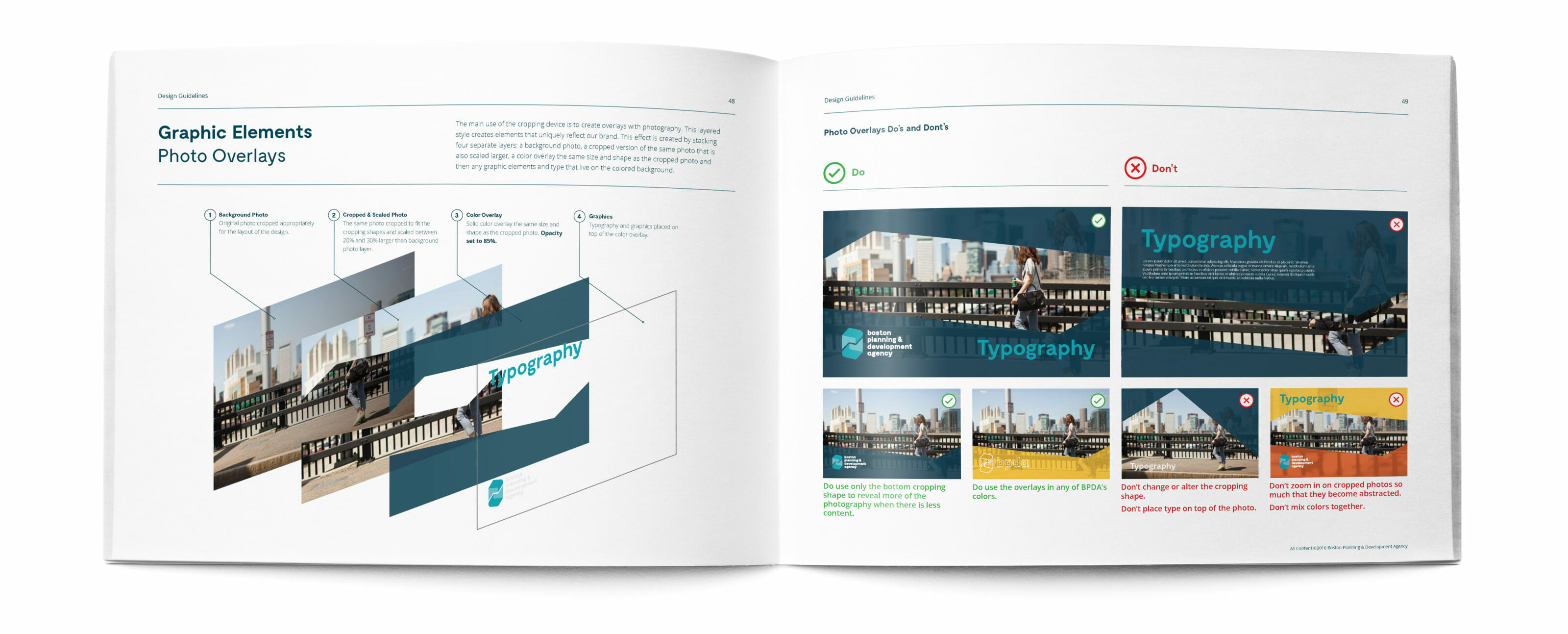

“The goal of the design was to strike a balance between a visual system that felt like it had the gravitas and seriousness of a governmental institution while also creating something that felt approachable and human,” says Continuum senior designer Tim Radville. “The system needs to be able to flex between an official document or research study and a poster promoting a community event.”

We took great care in crafting the logomark. From the BPDA website: “In its most basic form, it is an interlocking ‘p’ and ‘d’ that describes the interconnected nature of our primary functions. It can also be interpreted as an isometric view of a building. Finally, one can view it as two speech balloons, showing the dialog that we hope to create between us and the communities of Boston.”

The new focus of the BPDA would be to help Bostonians Live, Work, and Connect, and we developed icons for each. We picked a color palette of dark-blue and blue-green to reflect the BPDA’s values. “The color palette’s brightness helps convey both optimism for the future and the ability to find compelling insights,” says Radville. “Blue ties back to Boston’s location on the water along with its deep roots in the medical and education industries.”

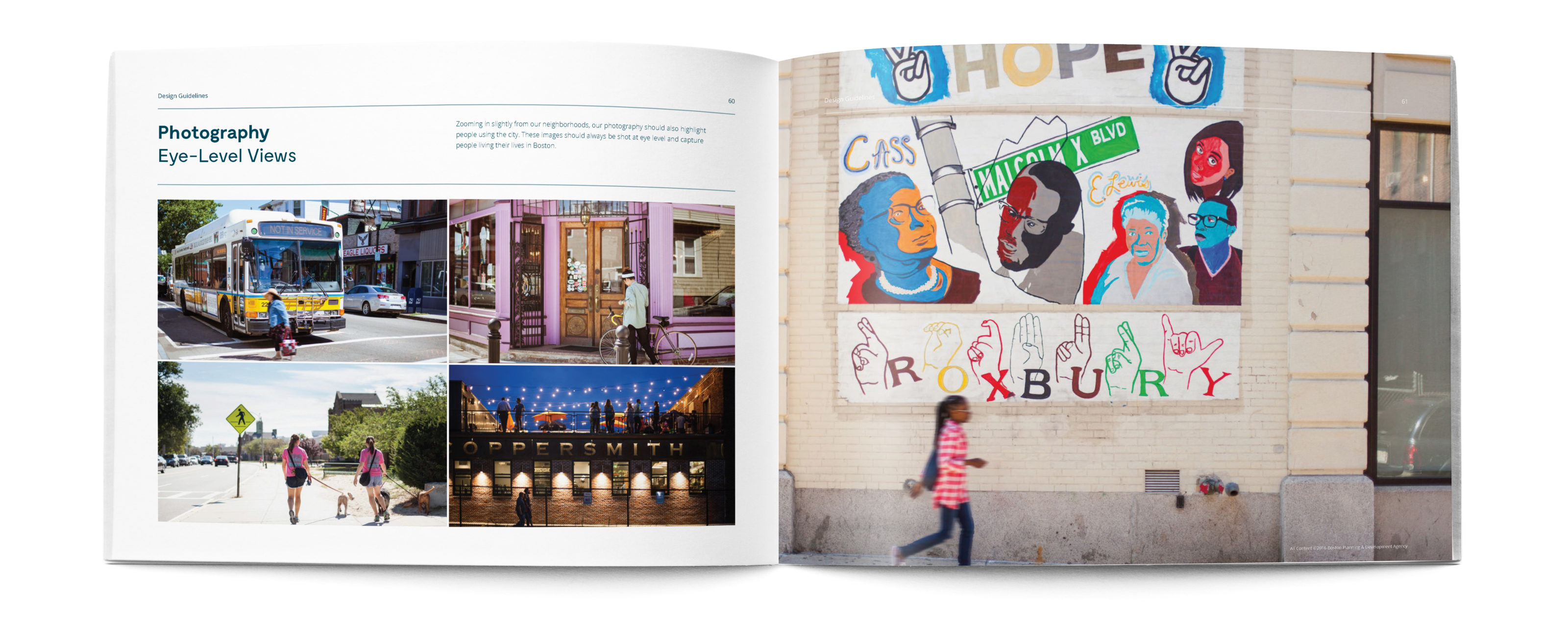

We drew up some nifty illustrated maps of Boston neighborhoods, and we used documentary-style photography, to best illustrate the people-centric nature of the BPDA, capturing what Radville calls “the real Boston, not the glossy version you might find in a tourism brochure.” We also insisted the BPDA speak in more human terms. Instead of saying, “Based on the city’s Inclusionary Development Policy, the rents on the affordable units will be set at 50%-60% of the AMI for the area,” they now communicate in terms everyone can understand: “Rents on these affordable apartments will be between $800 and $1,000 per month for one- and two-bedroom units.”

Four Key Pillars

In terms of the organizational redesign, we recommended four key areas of change: Engage Communities, Implement New Solutions, Partner for Greater Impact, and Track Progress. Each of these had an internal and external focus to ensure that the public-facing brand is mirrored internally with new ways of working within the BPDA.

Each of these pillars featured a framework intended to prompt internal BPDA teams to action. Rather than create a laundry list of tactics, or be prescriptive, we wanted to help foster culture change from within. Why? Employees needed to drive the change and own the content to create true, lasting, organizational impact. So we aimed to help employees themselves take responsibility for the organizational change. Personal ownership, we believed, would be most effective in impacting all the corners of the organization.

Roll Out

Together, we decided that the BPDA should create cross-functional, inter-organizational teams, with dedicated co-chairs, specific responsibilities, and a regular meeting schedule. Committing their people and time to the change was necessary, and we helped set the BPDA up for success. Teams would empower employees and raise the level of engagement, ensuring that this culture change was not merely a “top down” fix. We created an extensive website for BPDA employees and the public at large to spell out precisely what was at stake and how the organization should move forward. We determined with the BPDA team that a public website with the relevant insights and ideas would ensure continuous transparency and accountability.

And then we were very busy helping with the public launch in September 2016. We created invites, printed collateral, posters, new business cards, we even re-designed all the lobbies, painting them with new BPDA colors. The night before the launch, our staff was mounting the new BPDA logos on the walls of City Hall at 10 p.m.

On September 27, during his speech to the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, the Mayor publicly announced the new BPDA and its key initiatives. “The Boston Planning & Development Agency will be modern and state of the art, it will understand what cities of today and tomorrow need, and it will be innovative about shaping development toward those ends,” said Mayor Walsh. “With the combination of global leadership and community passion we have in our city, we deserve nothing less and we are fully capable of achieving it. I’m excited about the new possibilities we can unlock together.”

The day prior we held a huge private announcement for agency employees at Continuum’s studio. We had everyone there — the core team, extended team, the mayor’s larger team, and the entire BPDA staff — to celebrate this significant, important change to how the City of Boston plans and develops the urban environment.

Early Impact

One key indicator of how the organization is changing is how the BPDA now thinks about and rewards innovative thinking internally. On December 6, Mayor Walsh presented the newly created Innovation Excellence Awards to three BPDA employees — LeeAnn Coleman, John Swenson, and Anthony Verani — for their work on their new web-based Property Management Solution, which allows the BPDA to better manage its leases.

Now the tweets from Brian Golden, the BPDA’s Executive Director, share the positive impact of development when he’s posting about projects. Further, when the BPDA talks about new development projects, they feature elements of Live, Work, and Connect, like the number of new affordable units, the amount of new construction jobs, and the total number of new bike storage areas.

And the BPDA is opening things up. They now offer public tours, in their own space, of a scale model of Boston. The model is 1:40 inch scale and the half-hour tours are held every Tuesday between 10 a.m. and noon. It’s a wonderful way to interact with student groups and international visitors, and it shows the BPDA is excited to deeply connect with the people of Boston. New community engagement models are being explored as well, like the recent public walking tours of the L Street Edison Power Plant, slated for redevelopment in South Boston.

We admit it: our work with the BPDA is just the beginning. It’s going to take more than a new logo, a new name, and a new organizational strategy for the organization to gain the trust of the public and the media. But there are good, promising signs that the transformation process is well underway — after working so closely with them, we are optimistic. The organization is staffed with smart, energetic people who are willing and able to try new things, to step away from a broken past in the hopes of creating a better future. And creating a better future is precisely what you should expect from an organization called the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

From Design Museum Magazine Issue 003

Roadmap for the BPDA’s Future

Engage Communities: We suggested that the BPDA follow a five-step plan for improving the way they engaged with their communities: (1) Meet the people where they are; (2) Set the context for each project; (3) Define expectations and input needed; (4) Listen and analyze; and (5) Take action and communicate intent. We also envisioned what engagement might look in the future. For example, the BPDA should not just rely on community meetings but should also try text updates delivered to citizens’ electronic devices.

Implement New Solutions: To ensure that the BPDA’s solutions would not get stuck on someone’s desk or suffocate in a filing cabinet, we devised a set of guidelines that match their essential activities of Planning, Policy, Partnering, and Piloting (the 4 P’s) with suggestions that would help Bostonians better Live, Work, and Connect. We set each “P” theme against Live, Work, and Connect questions, and then provided some sample answers.

Partner for Greater Impact: Here we mapped out a matrix of partnership modes for the BPDA, listing possible partner types on one axis; and who would Advocate, Support, and Lead in these configurations on the other axis. We envisioned a future of partnerships, suggesting organizations to partner with, and described what might be accomplished — complete with examples.

Track Progress: Creating metrics is essential to the agency’s future success, and to help the organization do so, we created a four-step tracking process: (1) Decide what to track; (2) Gather data or feedback; (3) Analyze and translate; and (4) Show-and-tell stories. The most exciting elements are the forms of presenting progress. We envisioned using construction fences as an opportunity to update the public on how the project is helping the community.