Letter from the Editor

The Policing Issue’s Guest Editor shares the story behind the publication of this special issue.

Neighbors, 1972

By Jennifer Rittner, Guest Editor

I was 16 when a friend of friends was arrested. When it happened, it was obvious to all of us that this was the normal state of things. The arrests got closer. A boy I hung out with. A classmate from junior high. My next-door neighbor. Mostly the guys. Almost all in their late teens and early 20s. Among the writers in this issue, several report similar stories. A general awareness of police and the looming threat of impending arrest that menaced friends and loved ones. It colored our teen years, when we did what teenagers everywhere do: hang out, hook up, get lit, look cute, just chill. That awareness shaped our bodies, as some among us would posture in defiance, while others stilled their bodies into submission, willing the police to keep driving, don’t stop, go away.

Among the writers who contributed work to this issue, many have related similar experiences. Living in the shadow of prisons, witnessing loved ones in cuffs and squad cars, learning to look as innocent as possible as if to will the police away. The state of policing is one in which the oppression felt by marginalized communities is the normal state of things, and the means of change are so anemic that they feel more like wishful thinking than any realizable possibility.

The numbers are damning. According to The Sentencing Project, the United States is currently the overseer of 2.2 million mind-bodies being kept in legal bondage, away from their communities and loved ones, from their personal potential, from the possibility of a life beyond oppression.

The oppression we’re talking about is not just the condition of being arrested or incarcerated. As anyone following the news surely knows, it is often a matter of life and death. The Prison Policy Initiative reported, based on data collected in 2019 by Mapping Police Violence, that U.S. police officers killed 1,099 civilians that year alone. The second highest rate of police killings of civilians was in Canada, with 36.

While our attention gets pulled by the most recent cases, the problem of police violence against civilians did not begin with the murders of George Floyd (1973-2020), Eric Garner (1970-2014), Amadou Diallo (1975-1999), Eleanor Bumpers (1918-1984), or the dozens of others whose fatal interactions with the police make headlines each year. The problems of policing are also not segregated to Black, indigenous, and immigrant communities, though our communities continue to be disproportionately impacted. We also see how a culture of policing targets all bodies that are deemed abnormal or out of place, including those of us who live at the intersections of race, neurodivergence, gender diversity, and/or disability.

Problems of policing are rooted in the entrenchment of systems designed to enforce rigid rules of normativity, deciding who can thrive and under what conditions. In other words, we continue to keep people in their place by design. The design of systems determines where and how the presentation and aestheticization of our bodies, hair, clothing choices, walking styles, mannerisms, speech patterns, and cultural representations are acceptable, and therefore safe— and when not acceptable—then dangerous. Designers scoff at Adolf Loos’ strident treatise Ornament as Crime, but perpetuate his essential thesis, weaponizing Modernism to determine who or what has value, and deputizing gatekeepers from among the most historically privileged to maintain order that reinforces cultural supremacy. In the design of physical environments, constructed spaces determine where we are allowed to be and for what purposes. Those spaces are policed both by those deputized by the state to maintain social order, and by those who feel emboldened to deputize themselves as keepers of the unnatural order labeled by Isabel Wilkerson as the “American caste system.”

You will see in these pages that our writers and artists are not interested in advocating on behalf of “better” policing. We are not convinced that such a thing is possible. Rather than improvements to the practices of policing, you’ll read about the types of investments in civil society that negate the need for policing as we now know it. Our writers affirm a collective demand to feel secure: in our mind-bodies, genders, homes, streets, modes of transit, and wherever we find ourselves in private and public spaces. Security and safety, for many of us, come in spite of or in the absence of policing.

While this issue of the magazine is principally focused on policing, we occasionally point to the twin evil of mass incarceration. The prison Ponzi scheme has been designed not only to pipeline mostly poor, Black, brown, indigenous, and immigrant bodies into a system that brands them as damaged goods; but it also extracts from those incarcerated bodies and their families any and every resource that might enable them to thrive beyond the carceral state. The prison industry creates wealth for the system, while nickel-and-diming prisoners and their families for everything from adequate food and clothing to communications with loved ones, and legal counsel that can be a lifeline to liberation. A major labor force in the United States, federal prisoners (those deemed able-bodied) are required to work on behalf of the prison economy, earning $.12 – $.40 per hour while producing goods and services that earn the prison system over $2 billion in revenue. Prisoners, meanwhile, earn barely enough to buy subsistence goods for themselves (food, toothpaste, books) let alone to help them pay off debts or help family members on the outside.

Designers who have worked for McDonalds, Walmart, Starbucks, Victoria’s Secret, Fidelity Investments, or American Airlines, have contributed to the prison-labor machine, as goods by these brands are often produced by substandard-wage workers in prison. In a Machiavellian twist, prison labor also produces the tools of policing, including body armor and holsters for weapons. Injury, meet insult.

So no, this issue is not calling on designers to fix the problem of policing by collaborating with existing bureaucracies. Our writers do not believe that the industry can “design-think” its way to a solution. Rather, we are hoping to reveal some of the ways in which models of dominance and dominant-cultural supremacy frame design practices, and have entrenched some of the same oppressive inequities produced by policing.

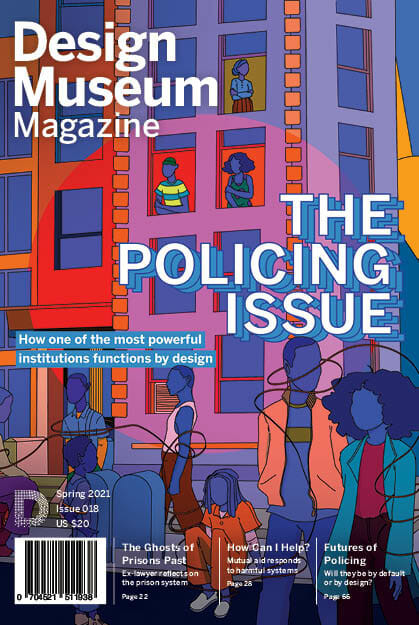

To the extent that this issue is a critique of policing, it also affirms a vision for something better. North Carolina-based illustrator, Blacksneakers, designed the cover art, which offers her view of a multi-generational, civil society absent of policing. Our cover artist further contributed to an essay in which Ajay Revels and I reflect on ontologies of policing. In an article illustrated by Jon Key, author and former lawyer David Lamb shares his revelation that his work as a public finance lawyer in the early 90s supported youth prisons in rural America. Lamees Rahman illustrates the invisible threads of policing in a piece co-authored by Sarah Fathallah and A.D. Lewis’s critique of design thinking methods that uphold the dominant, hegemonic cultural supremacy. Jamie McGhee, in an essay beautifully illustrated by Ariel Sinha, gathers the voices of artists, writers, and designers on the future of (and without) policing. Social activist and poet Niki Franco led a provocative roundtable discussion with Ivy Climacosa, Dustin Gibson, Annika Hansteen-Izora, and Liz Ogbu, in which they reflected on abolitionist activism and the intersections of design and social justice. Social justice takes the form of mutual aid systems in an article co-authored by Stephanie Yim and Shanti Mathew, with art by Myanh Walker. CoDesign Collaborative resident designer Sophia Richardson, who worked with all of the artists on this issue, illustrated the essay in which Timothy Bardlavens and I unpack specific objects of policing. Ajay Revels also served as lead researcher on the project, supporting the writers with data points and resources throughout the process.

Organizing the entire process of preparing this issue was Jennifer Jackson, who is perhaps the most competent and patient colleague I’ve ever had the pleasure of collaborating with.

It has been an immense honor working with all of the writers and artists on this project, as well as the incredible team at CoDesign Collaborative. On behalf of the writers and artists involved with this magazine issue, thank you for supporting this project. We look forward to continuing this conversation.

Sincerely,

Jennifer Rittner

Guest Editor