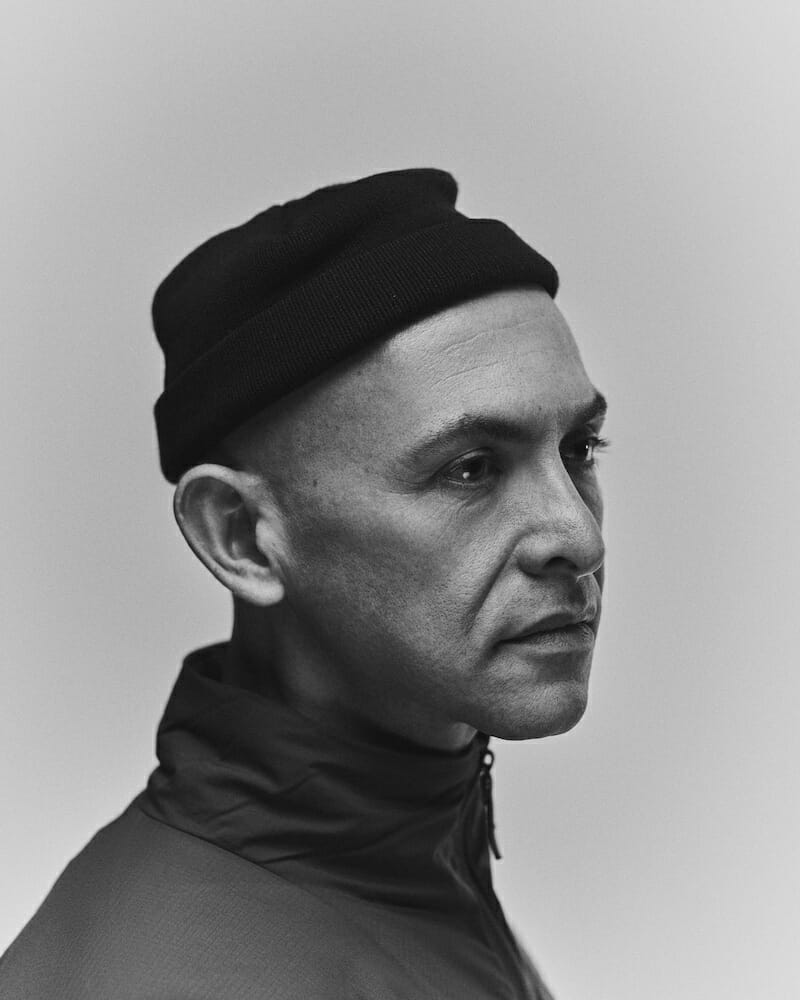

Lifelong Learner and Teacher

An Interview with Josh Owen

Josh Owen discusses childhood inspiration, balance, and what it means to be a designer.

Photo: James Bogue

Interviewed by Kristin Grant; Photos Courtesy of Josh Owen

When I first met designer and educator Josh Owen, I was an anxious, pimply 18-year-old beginning my first semester of industrial design at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). To us freshmen, the Chair of the Industrial Design Department loomed like a designer god among men. Owen lectures all around the world, has work in numerous museums, and wins countless design awards. Better yet, he always takes students along for the ride with exciting class projects. That being said, Owen’s path to design success was not as linear as we might expect. With a background ranging from anthropology and sculpture to music and design, Owen has since channeled his multitude of life experiences into a distinctive point of view. He is an excellent mentor and friend, dispensing wit and wisdom daily in the classrooms at RIT, all while maintaining a robust professional practice. How does he do it all? CoDesign Collaborative wanted to find out.

Kristin Grant: What elements of your upbringing contributed to your interest in design?

Josh Owen: It’s hard to tease out all the twists and turns of a complex career roadmap, but I am certain that growing up in an academic household contributed greatly to my being curious about the world around me [Owen’s father was an archaeologist at Cornell University]. That’s probably the foundation of a lot of designers being inquisitive about history, cultural context, and the way the built environment is reflective of human choices. Being a critical observer is what allows designers to scrutinize where challenges and opportunities are. Growing up as the child of a professor, I was incredibly lucky to spend a lot of time with my father and his students in critical contexts. Because his field was archaeology, I was exploring history and materiality by participating on archaeological excavations, drawing connections between what we unearthed and that which we could connect to existing knowledge. These experiences looking at the world through historical artifacts helped nurture the seeds of my creativity.

KG: You majored in anthropology and sculpture. How have these fields influenced you as a designer?

JO: When I applied to university I had never heard of industrial design, and there was no one in family that knew much about architecture or design. So I think I was following my natural instincts, which fell into a couple of camps: studying culture and making things. Anthropology and archaeology surrounded me as a kid, and drawing and interpreting the world by making things was a kind of natural curiosity that I always explored.

When I was an undergraduate, Cornell had an infrastructure that allowed an individual to pursue two degrees within a five-year period, which appealed to me. The fine arts major allowed me to focus on sculpture and the liberal arts major gave me the opportunity to study anthropology. The materiality and form-giving that I learned from sculpture, combined with the human and behavioral aspects from studying anthropology, formed the basis for my interest in becoming an industrial designer.

KG: How did you discover industrial design?

JO: I like to think that I “came of age” during my junior year study abroad experience in Rome, Italy, where I witnessed the historical evidence left by individuals like Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Bernini, and others who history tends to recall primarily as artists. But I began to understand that these creators were acting much as designers do. They were interpreting clients’ requests across many mediums: architecture, engineering, painting, and sculpture. They were solving problems by delivering messages in the form of environments, experiences, and things. This understanding helped me realize I wanted to combine my interests and focus them into a career as a designer.

KG: What were your aspirations as a young designer and how have they evolved?

JO: When I began my career as a young designer, I wanted to work on projects that would allow me to exercise my point of view. I think this aspiration has remained with me, seasoned over time by my increasing desire to make meaningful choices that move humanity forward, taking my students, clients, and colleagues along for the ride.

Photo: Elizabeth Lamark

KG: Now, as an established designer, what is your favorite product you’ve created?

JO: Picking a favorite project is a bit like asking somebody who their favorite child is. I feel that in some ways all my projects have had their merits – even those that have failed in some way. I have to say that I’m proud of all of them. I’ve been able to pick and choose my clients and projects pretty carefully over the years. I have limited time and bandwidth, which forces me to work on what’s most meaningful. I suppose overall I’m most proud of the totality of my work, much of which I have shared in my book, Lenses for Design.

Photo: Will Kelly

KG: How did your design career eventually lead you to teaching?

JO: To be honest, I never really intended to have a career in teaching. When I finished my graduate work at Rhode Island School of Design, I moved to Philadelphia to be with my girlfriend, who eventually became my wife. I started working by seeking freelance projects to get into the industrial design community. These were mostly in New York City, which was pretty easy to get to from Philly.

I was eventually somewhat coerced into teaching part-time in Philadelphia University’s Industrial Design program. I was happy to do it, and I was curious about teaching. It snuck up on me, as I was surprised by how much I liked it! So I took on a few more courses as a lecturer. After a while, a full-time opportunity opened up there. I applied and received it. Thus began my career in design education in Philadelphia, maintaining my professional studio all the while, trying to keep a balance of an academic and professional career.

KG: What do you enjoy the most about being an educator?

JO: Definitely when my students succeed. My definition of success involves being socially conscious. I derive a great deal of joy from helping others succeed by sharing my own experiences, networks, and knowledge.

KG: What is the most challenging?

JO: Designers tend to thrive off constraints. I try to see the challenges with teaching, or anything, for that matter, as the constraints that come with the context I’m working in. Reframing the challenges yields the results which are the most satisfying when they are distilled into successful outcomes.

KG: What is your teaching pedagogy?

JO: My pedagogy focuses on the integration of professional sector experiences and evidence into industrial design education. Over the last decade I have developed coursework that adjusts to graduate and undergraduate levels while embracing the use of historical artifacts and industry partnerships in the process.

I teach an undergraduate fourth-year design studio called the Metaproject and a graduate-level design laboratory referred to as Activating the [Vignelli] Archives. Both of these initiatives seek to pull best practices from history and industry and merge those with the experimental and contextual characteristics to create value for all involved.

Photo: Elizabeth Lamark

KG: How do you balance your professional practice and teaching?

JO: I manage to take care of my professional practice by focusing heavily on it for a few days each week during the academic year and squeezing it in between things. During the summers, I spend four days per week working with a team of mentees in my studio. I do a lot of heavy lifting at this time, when I can focus for three months on client-based work.

KG: What is one piece of advice you wish you could give all design students?

JO: Be passionate, open minded, and flexible, but operate with purpose.

KG: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

JO: I hope to be doing more of the same, but better. I want to continue to learn more and evolve more, always with the goal to contribute to society in meaningful ways. I do my best to be open to new opportunities. I doubt you will see me dramatically changing careers at this point, but I do pull in new directions as I go. I think if you look carefully at my trajectory, it’s been a steady progressive climb, enhancing all the areas where I’ve been able to help others with my imprint. More but better!

You can find Josh’s book, Lenses for Design, on Amazon and at the RIT Press.