Leveling Up STEM

By Jessica Sanon

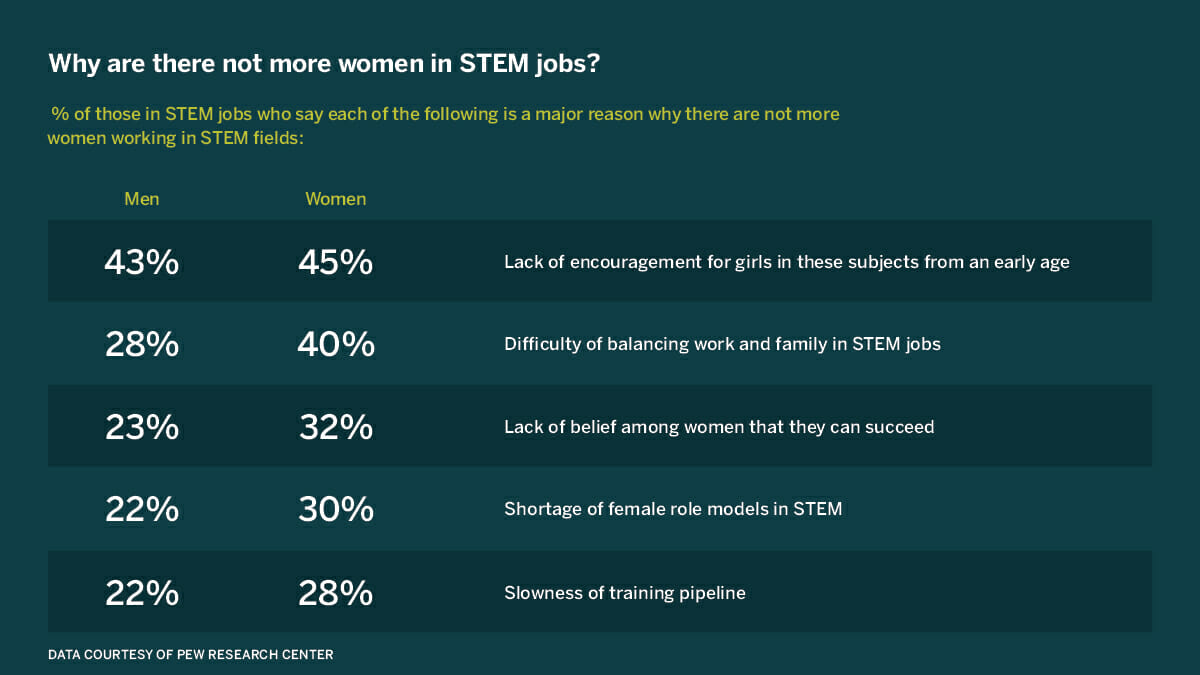

Let’s face it. Part of the reason why we do not see more women of color in STEM fields is the embedded stereotypes and assumptions of what it means to be a STEM woman.

We have seen women such as Katherine Johnson shift the narrative and show why BIPOC women are an invaluable resource in the STEM community; yet, these same women often do not receive recognition in our society. Instead, when we highlight people who have made significant achievements in the STEM or entrepreneurial worlds, white male figures are the examples we show our students the most often, leaving no room or lasting impressions of what others have done and hampering young girls’ ability to imagine what is possible for them in the professional world of STEM.

Social constructs have gotten in the way of the encouragement process of getting girls to remain interested in the STEM fields. Despite educational progress over the past several years, high school minority students still lack access to the educational resources that will prepare them for college success. Only about 40% of public high schools serving predominantly Black students offer physics and about 33% offer calculus. Additional data gathered from the Department of Education shows that Black students are much less likely to have access to Advanced Placement courses in STEM fields. The correlation between students’ preparation for STEM-related jobs and the lack of access to foundational STEM skills puts Black students at a more significant disadvantage in preparing for advanced STEM courses in college and future careers in STEM. The lack of opportunity and access to a rigorous curriculum in many public school systems located in inner cities has also caused an imbalance in students’ cognitive growth. From negative stereotypes to lack of encouragement from their surroundings, women, especially BIPOC women, do not see themselves in STEM.

Some reasons why there are not enough BIPOC women going into STEM include:

- Lack of mentorship or representation in the field

- Negative stereotypes surrounding girls who pursue STEM

- Lack of encouragement from educators, family, and peers

- Self-discouragement in pursuing STEM

In creating sySTEMic flow, my mission is to bridge the gap between STEM education and math literacy for BIPOC girls and women interested in STEM through a holistic approach that ultimately combats this retention issue. My personal journey to finding the STEM field began in my early child-hood, when I found my passion for math. My personal experiences with grappling with my identity and finding the confidence to pursue my dreams led me to found sySTEMic flow, so that other young women could feel supported in their decisions to move against the status quo and embrace their passion and potential in STEM.

The Beginning: Finding the Flow

Ever since I was a young child, I always had a strong interest in all things math. I grew up in a Haitian household, and learning English was one of the biggest obstacles that I had to overcome as a young person. As a result, I was so shy, and I had a myriad of speech issues that I also grappled with, but unlike conversation, math felt incredibly natural to me. It was something that I invested my time in, that I was passionate about, and that gave me confidence throughout my childhood.

I wanted to prove my family wrong. I wanted to prove society wrong. If I didn’t have that kind of mindset, I don’t think I would be where I am today.

I decided to major in Mathematics and Statistics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and my original goal was to be a math teacher. But as I progressed through college, I became exposed to so many other potential career pathways in science and mathematics. The fact that I did not have this realization until I arrived at a university made me realize that my lack of exposure to the various potential careers in STEM was a hindrance to my academic and ultimately professional aspirations. I also began to feel myself become intimidated by the rigor of collegiate STEM courses and lose my confidence in the very subjects that used to uplift me in my adolescence. It truly was my persistence and passion for pursuing a career in STEM and my determination to transcend the traditional role of women as caretakers that I had been brought up with that fueled my ability to succeed in college and beyond. I wanted to prove my family wrong. I wanted to prove society wrong. If I didn’t have that kind of mindset, I don’t think I would be where I am today.

Through my journey in my four years at UMass, I realized that a lack of academic preparation, not finding people in the math field who looked like me, and a dearth of read-ily accessible internship opportunities contributed to my initial difficulties in college. I determined that my calling was to do every-thing in my power to make sure that young BIPOC girls did not experience the same hindrances that I did, and in my personal statement when applying for The Heller School for Social Policy and Management’s Master of Business Administration program in Social Entrepreneurship and Impact Management at Brandeis University, I pitched the first iteration of the organization that would one day become sySTEMic flow.

While learning the fundamentals of starting a business at Brandeis, in 2017 I had the opportunity to pitch my idea for sySTEMic flow at a startup competition event, where it won second place. It was then that I realized that people actually see the value of sySTEMic flow, that there are actually women out there who ended up switching their major or not pursuing a career in STEM because of avoidable circumstances, and that we at sySTEMic flow could combat this apprehension of women of color toward pursuing a career in STEM and elevate these women to reach their fullest potential and achieve their biggest ambitions.

The Solution: sySTEMic flow

After working through various iterations of our business model over the past few years, which involved networking at local schools, cycling through different mentorship models, and recruiting interested students to work with us, we eventually arrived at our current organizational structure. In 2020, when the pandemic hit, we really assessed how we could create virtual academic programming that could supplement the unpredictable academic environment that COVID-19 certainly exacerbated, but that has also consistently been a problem for students in underserved communities. We formulated a 13-week, after-school math program for high school students, in which students meet twice a week for 90 minutes to augment their regular math education with compelling activities such as bingo, jeopardy games, and a math escape room. We also offer office hours for two hours a week, so that students can get even more specialized attention for their math-related questions.

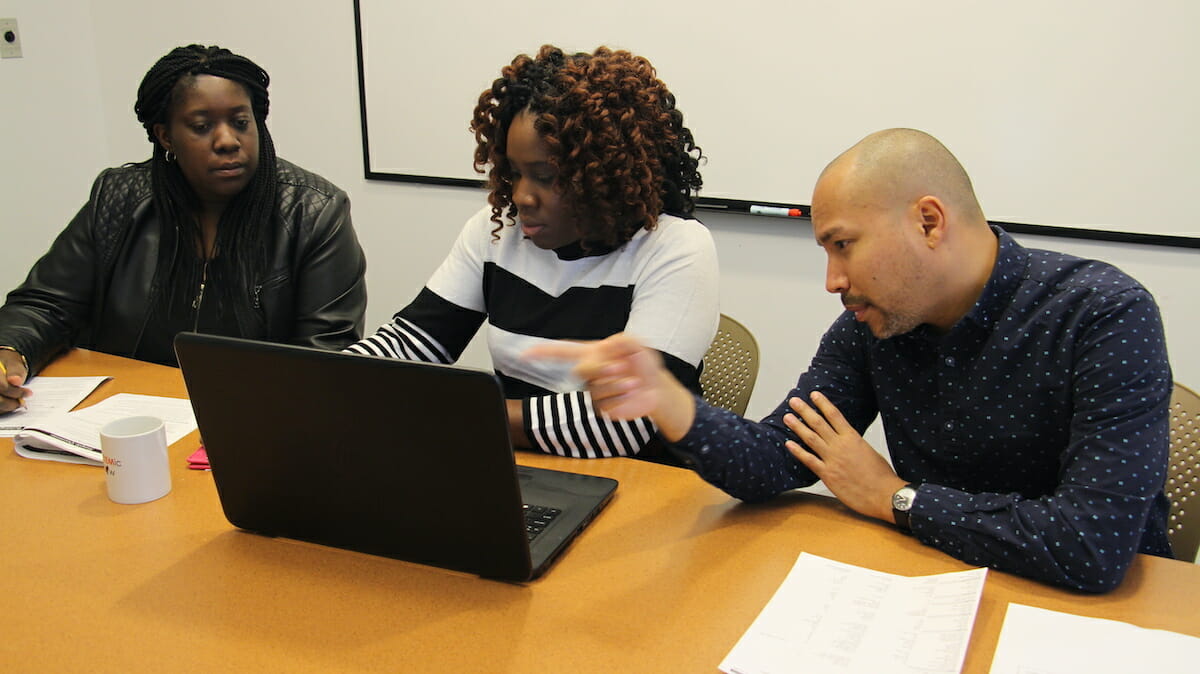

We also work with students who are interested in finding an internship or mentor in STEM to optimize their resumes and cover letters and help them network in the field. Every month we have a MySTEMStory event, where we engage with BIPOC women who are professionals in STEM and allow our students to more clearly visualize the potential for a career in STEM through connecting with these role models. These are just a few elements of our holistic approach, which tackles this multifaceted problem through a three-tier process: academic preparation, mentorship, and workforce development.

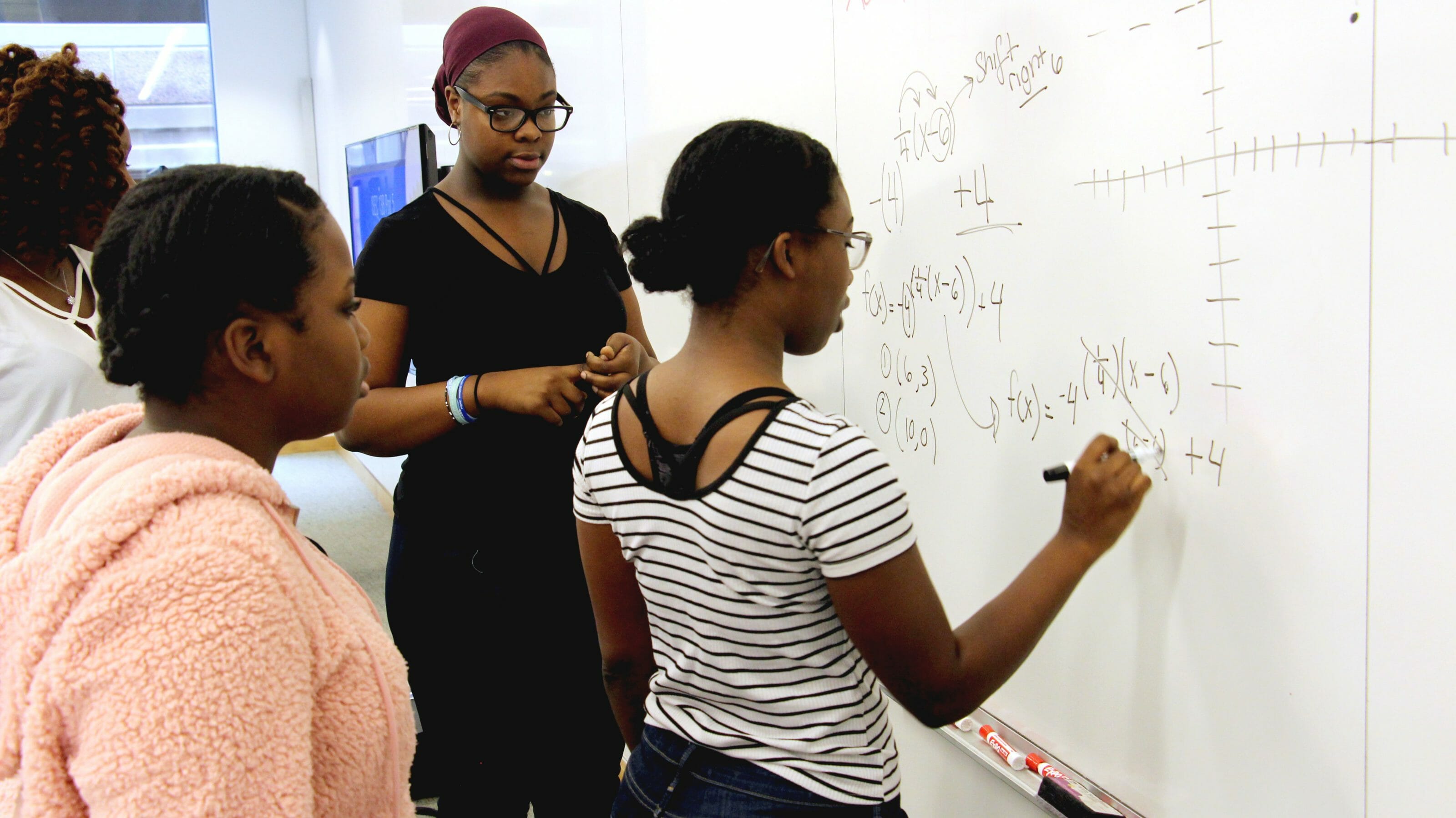

Academic Preparation: Redesigning the Classroom Environment

We have redesigned the classroom experience so that it is conducive to how girls see themselves in STEM. We think beyond the numbers and lectures and focus on students’ individual growth through a flipped classroom and scaffolding approach. In a traditional classroom setting, students begin by learning concepts first—through instructors providing an overview—and then students’ knowledge is tested through homework assignments. The difficulty with this approach is that the problems assigned to students for homework are oftentimes a lot more complex than what they see in class. Additionally, this teaching style caters to a subset of students who can grasp concepts fairly quickly, making it more difficult for learners who need additional support in class. Our “flipped classroom” model, however, gives students control over what they learn and how they learn. This approach is more student-centered and invites collaboration among peers. Lessons and content are provided in multiple ways, allowing students to deepen their understanding in a way that works for them. This framework forces educators to trust students more and gives them the space to think independently and broadly, to shift their mindsets to “I know I can.” Flipped classrooms provide all students an equal opportunity to learn, self-learn, encourage peer learning, and gain confidence in various mathematical concepts.

Scaffolding Approach for Designing a Math Curriculum

We design our curriculum using a scaffolding approach that can modify the learning experiences of our students to optimize progress. We have created a curriculum that is easy to read, digestible to the eye, and provides youth with relevant information (5). Each lesson is divided into specific categories: key terms, how the math topic is seen in everyday life, and a step-by-step guide on solving easy to complex problems. We use mixed written interactions within our curriculum, such as fill in the blanks, definition scavenger hunts, and underlining key phrases to engage the youth to think beyond problem-solving and really find ownership of the concepts. In addition to the curriculum, students are encouraged to research BIPOC women currently paving the way for access and employment opportunities in STEM and to share their findings regularly with their peers in the program. This shows students that beyond learning math, there are also social and communal aspects of STEM that can be tapped into through research, discovery, and collaboration.

We have redesigned the experiences and interactions girls have with math to empower them to make decisions on their own and self-guide their journey in STEM. By helping these young women to find their confidence in math concepts and discover potential careers that these skills could funnel into, we are striving to reduce the barriers or obstacles that they may face in pursuing a STEM career.

Mentorship: Amplifying Stories Designed with Lived Experiences

In our programming, we intentionally bring in guest speakers who can discuss STEM concepts that students may not be exposed to in a traditional educational setting and encourage girls to explore the multitudinous opportunities that a STEM career can offer.

Women in STEM continue to call for active community participation within spaces today. For example, Lorena Soriano, Founder of every POINT ONE, who was recently featured in Forbes “30 Under 30,” cites the powerful presence that can be achieved when women of color come together and form a community to surpass their shared sense of “imposter syndrome.” This perpetual feeling of not being up to par is reinforced by existing in a space that inherently shuts Black and brown folks out, making those who gain access to it question their worthiness. At a 2017 conference tackling diversity in STEM, Olivia Graeve, a UC San Diego professor, concurred by encouraging peers to devote resources toward community-building because of the extreme impact it has on students’ success (per her own first-hand experience). Women in STEM—and mainly Black and brown women in STEM—rely on creating relative space out of necessity, as it directly correlates with their ability to survive and thrive in institutions designed to keep them out (6).

Workforce Development: Changing the Way We Think about STEM-related Careers

We often see with our students that there is a lack of understanding of the variety of careers that are available involving math. We tell them that math is not just about solving problems; rather, you become a problem solver. The skills and knowledge gained from studying disciplines in STEM can provide students with limitless employment opportunities. Further, BIPOC women enter a world that is not designed for them, and they are forced to reckon with adjusting to the collaborative, communicative, and personal requirements once granted access to this space. Their learning does not solely come from textbooks and pens, but by working with people on a human level within a space that routinely isolates, stigmatizes, and oppresses them.

Procuring a mutually supportive environment with growth opportunities is essential for BIPOC women in STEM. Inclusivity functions as a multifaceted tool for both leveling the playing field and enabling pathways for success. The system fails Black women in its inability to create an environment they can thrive in; thus, the industry loses all too many bright and capable minds. BIPOC women in STEM must be prepared with the necessary tools and training to assume leadership positions.

To combat these inequities, employers will need to start interacting with high school youth more, showing them what kinds of opportunities are available in the industry.

This approach will help employers understand the support required to cultivate the next generation of STEM professionals, and how organizational culture needs to be restructured to optimally support them. The more Black and brown women we see as leaders in STEM, the more role models that upcoming talent has to inspire feelings of courage and possibility for them. From there, we can begin to shape a cycle of systemic change in which BIPOC women are properly provided the opportunity to hone their abilities and achieve professional success.

It is here that we see the intersection of diversity and inclusion. Commitment to diversity broadens the scope of talent pools and is proven to fuel innovation in STEM. Simultaneously, fostering greater inclusivity provides the framework by which women of color can assume positions of power, activating a new cyclical, systemic order in which their voices and contributions can be better heard. Leaders in the STEM industry must do their part to hold diversity as a hiring priority, not just among their teams but also in leadership positions.

We tell them that math is not just about solving problems; rather, you become a probIem solver.

The STEM field is in desperate need of institutional, structural change to properly nurture these young minds—both in the breadth of the positions available and in the depth of career advancement when on the STEM track. Our holistic approach to retaining women’s interests in STEM and nurturing their development will serve to augment this evolution within the industry. In the future, we hope to evolve our organization to reach even more students and schools by diversifying our programming and bolstering our in-person and online presences, and to directly connect with universities, helping students to gain collegiate experience and credits in high school, and giving them even more of an edge as they pursue their goals in STEM.

Our work at sySTEMic flow seeks to prepare and empower young Black girls to take STEM by storm, not just as bright minds but as capable leaders. We are committed to filling in the gaps and instilling the lessons needed to succeed in today’s world, laying the foundation for a career that will change the course of the industry.

To learn more about sySTEMic flow and how you can help them in their mission to further the education of BIPOC women in STEM, please visit their website at:

www.systemicflow.com

Sponsor a student by following this link: ifundwomen.com/projects/what-can-you-do-about-women-stem-right-now

Thank you to former sySTEMic flow Marketing & Social Media Specialist John Snow for your work on our sySTEMic leaders articles, which are cited here.

(2) https://www.usnews.com/news/stem-solutions/articles/2015/02/24/stem-workforce-no-more-diverse-than-14-years-ago

(3) https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/fact-sheet-spurring-african-american-stem-degree-completion

(4) https://edventures.com/blogs/stempower/the-past-present-and-future-of-women-in-stem

(5) https://www.systemicflow.com/online-math-institute

(6) https://www.systemicflow.com/post/the-bunching-effect-dr-shirley-jackson

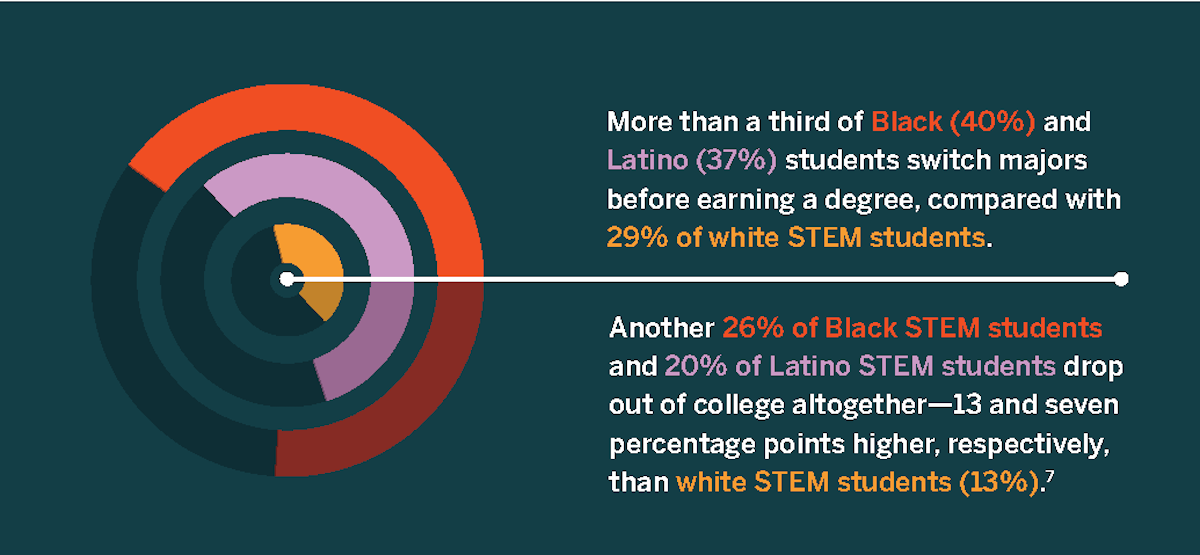

(7) https://eab.com/insights/daily-briefing/student-success/a-third-of-minority-students-leave-stem-majors-heres-why

(8) https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/01/09/women-in-stem-see-more-gender-disparities-at-work-especially-those-in-computer-jobs-majority-male-workplaces

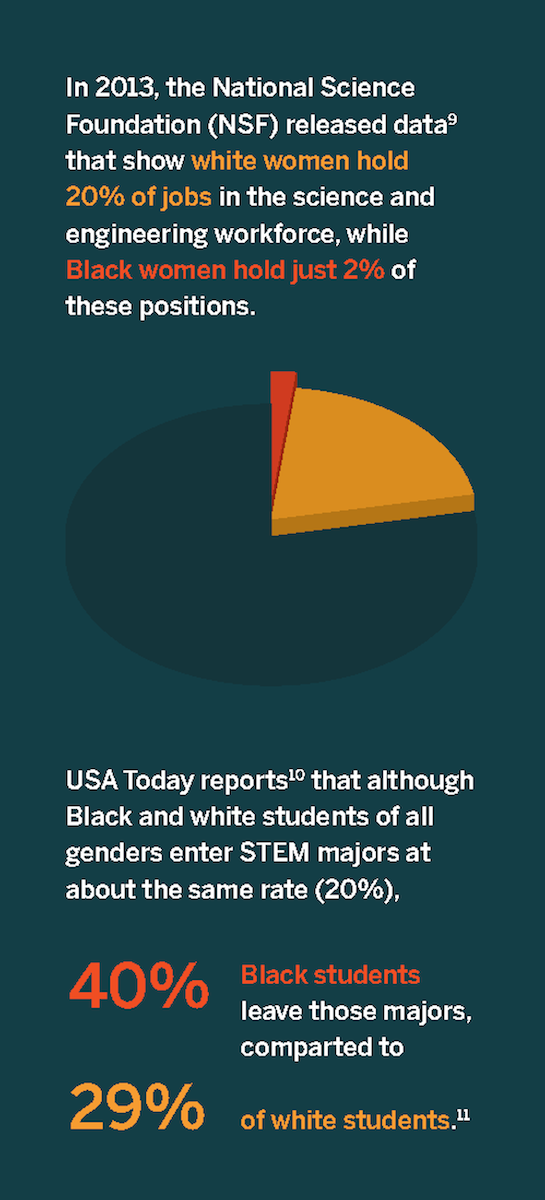

(9) https://wayback.archiveit.org/5902/20160211074856/ ; http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2015/nsf15311/digest/theme5.cfm

(10) https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2020/12/03/why-universities-need-reform-stem-education-protect-economy-column/6462405002

(11) https://barnard.edu/news/supporting-black-women-stem-careers