Inclusion Applied Creatively

Kat Holmes

Kat Holmes began her career in mechanical engineering, but found her design calling while working on many different technologies at Microsoft. Her path of curiosity revealed a common theme in her work: inclusive design improves our interactions, both with humans and machines.

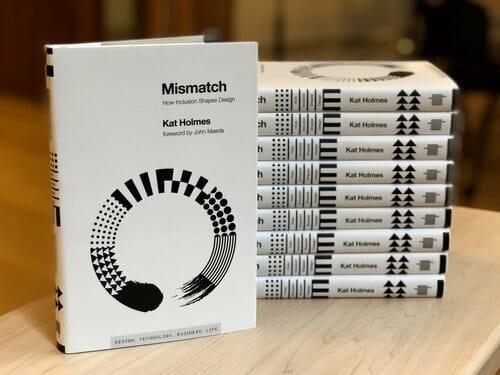

Kat Holmes is the author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design and Director of User Experience at Google

CoDesign Collaborative recently caught up with Kat to learn more about her new role at Google, staying curious, and finding the beauty in complex challenges.

Mary Lewey: How did you find design?

Kat Holmes: Growing up, I didn’t know anybody who was a designer for a living. I knew engineers, I knew artists, and both had a big influence on my life. I wanted to find a way to merge the arts and sciences through something that was both technology and human focused. My role in design became clear while I was at Microsoft. It was the first time I worked for a software company and I was able to work on so many projects from mobile phones, to wearables, to holograms, and more. Every team I worked with struggled to some degree in thinking about who exactly we were designing for. That became the heart of design for me, which is: how do we think about diversity of people? How do we develop new methods, new ways of working, that help us do better?

ML: When did inclusion become part of your career path?

KH: Inclusion became a deep interest in college, especially because of the potential of what technology could do, if applied creatively. How it could connect to people, be a part of their lives? Why are we here making all these complex technologies if not for some human purpose?

At Microsoft, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to make it my job. My first introduction to accessibility coincided with working on new digital assistant and voice-based interactions. Our team was designing a voice-based interaction with an assistant and met a community of people who have been talking to their computers for 20 years because they use speech commanding when authoring emails or writing code. Keyboarding wasn’t the primary way they used the computer. I started to see similarities in these separate conversations and they led to the first real clear steps toward considering what inclusive design is. How does inclusion show up in what we create? How does the make-up of our teams lead to designed outcomes?

KH: I started my own company to advise and consult on inclusive design. After writing a book, Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design, the company is evolving into a platform called Mismatch.design, featuring educational resources, stories, and free content where people can read about inclusive design. I am also a UX Design Director for Google’s advertising platform. I’ve always had mixed feelings about advertising and wasn’t sure why. But it is the economic engine for such a huge portion of companies that are working to develop all these types of technologies that we’ve been talking about. My big question from an inclusive design perspective is: what does economic inclusion look like? How can businesses and the tools we use to build them be more open, more accessible to more people? When this opportunity came up, I was excited about: a. learning more about how that part of our industry works and, b. how that can lead to large scale types of economic inclusion.

ML: What is fulfilling about your new role?

KH: I work with designers, engineers, and project managers who love complex problems. When I was consulting, every company I met was thinking about how to design for complexity. For example, how do we design products that are going to be used around the world by people who speak dozens of different languages? For a long time, a lot of design and engineering methods focused on how to create simplicity. And that isn’t always the solution to complexity. It’s fulfilling to work with people who both appreciate and find beauty in complexity.

ML: What is challenging about it?

KH: Being new is always hard. And not knowing things. I love being in that space, but it can be challenging to be the person in the room who knows the least about something. New job, new topic, all at once, some days can be harder than others.

ML: How did mentorship play a role in your design journey?

KH: Mentorship isn’t just someone more senior in their career or who’s more experienced. For me, it’s about finding people who lead with curiosity. I’ve never taken the career mindset of trying to get to the next level. I’m led by what I want to learn. When I start to pursue a new interest, I go out and find who else is curious about that topic or is asking similar questions. A lot of the time, what I pursue overlaps with other interests that I didn’t know intersected. Once I see how they may intersect, I find someone who is also thinking about that combination. It’s definitely shaped how I learn and taught me to seek out people who have curiosity about the intersection of unlikely combinations and then have good conversations with them on what’s possible at those intersections.

ML: Who or what inspires you?

KH: Unlikely combinations. Because they challenge the way I think about categories in the world and test my existing notions and assumptions.

ML: Of all your skills and talents, which do you appreciate most, and why?

KH: My ability to listen for the connections and underlying motivations.

ML: What advice would you give to your younger self?

KH: Courage is a team sport. Put yourself out there and know that you’re not alone.