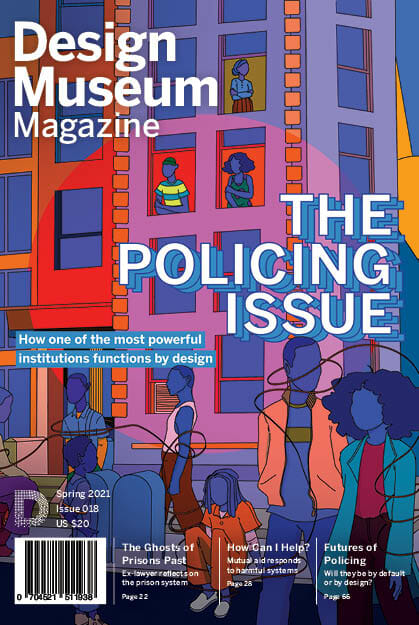

How Can I Help?

Mutual Aid as a Response to Harmful Systems

Shanti and Stephanie discuss mutual aid’s historical and current purpose: to support communities when other systems fail.

Illustration by Myahn Walker

By Shanti Mathew and Stephanie Yim

Anatomy of an Arrest

In New York City, when an individual is arrested, they are stripped of their belongings and thrown into a black box, disconnected and isolated from their families, friends, and communities. Sometimes they’re allowed to make a call on a dial-pad phone to a number that they must have memorized. They must hope that someone picks up a ringing phone—no matter the time of day—and comes to their aid.

Once arrested, the individual is shuffled between police precincts and then eventually transported to the arresting borough’s central- booking facility. They will wait between 24 and 48 hours in a squalid cell crowded with other arrestees and one metal toilet littered with feces and urine. Without information and sustenance except for a slice of cheese between two slices of bread, they wait for their arraignment hearing, at which time a judge will determine if they remain in jail, can be released on bail, or return home for a later court date.

In the last published report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, almost 90 percent of defendants are indigent and don’t have access to legal support before their arraignment. If they cannot afford their own private counsel, they will be assigned a public defender 15-30 minutes before arraignment. Once their arraignment hearing begins, they will be read their charge(s) and asked how they plead. Thirty minutes is not much time to do justice for each defendant, and to find the best argument for their freedom.

By law, a judge is meant to determine the outcome of the arraignment based on the individual’s risk to flee and not appear for their future court dates. However, data continues to show that only a small percentage (15 percent in 2017) of those released, regardless of charge severity, missed one court date.

Instead, frequently a judge determines the outcome of the arraignment based on the individual’s ties to their community. An existing job, a permanent home address, someone the client can call, or a loved one who can show up at the time of arraignment. These are all imperfect representations of community ties that can significantly impact the outcome of an arraignment, including influencing the bail amount that is set. In this system, those who are homeless, unemployed, or separated from their families are penalized. Further penalized are the poor, who will land in jail because they or their loved ones cannot afford their bail. In this system, freedom has a price tag.

At this very moment, there are over 7,500 people sitting in pretrial detention in New York City, waiting for their trial before being convicted of any crime. That number is about 77 percent of the average daily population in jail. Even though our Constitution ensures a speedy trial, prosecutors in New York City can stop the trial clock until they are “ready” for the trial, causing the average lengths of stay in jail to vary greatly. On average, people are detained for over 57 days for nonviolent felonies.

Detained in jails like Rikers Island and The Boat, people, including incarcerated youth, experience violence from corrections officers and inhumane conditions. Kalief Browder, a teenager who was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack in the Bronx, spent three years on Rikers awaiting his trial. Of the three years, two were spent in solitary confinement. Browder committed suicide two years after his release at the age of 22. Browder’s tragic and horrifying story has pushed criminal justice reform in New York City in the last few years—many years too late, some might say.

From the moment they are arrested, an individual’s path is laden with hurdles to returning home safely without the lifelong con-sequences of a criminal record. From the beginning, the police, court, and system are designed to break individuals physically and emotionally. Under the pressure of repeated violence and dehumanization, an individual is likely to accept a plea bargain to escape their horrifying situation. In a report published by the Vera Institute of Justice, pretrial detention increases the chances of a jail sentence by 40 percent for misdemeanors. An unwarranted arrest for a low-level crime, or worse, a wrongful arrest, can ripple through an individual’s family and extended community, tearing lives apart.

Policing in America

The history of policing in the Northeastern region of the U.S. begins with the founding of Boston’s night watch in 1636, a group of volunteers who would keep watch of the town at night to warn of impending danger. It wasn’t until the early 1800s that night watches would transform into police forces that employed full-time police officers. The formation of these first forces were largely supported by merchants, who wanted police officers to maintain the “orderliness” of their workforce and the urban environments in which they conducted their business.

Rather than mercantile interests, policing in the American South has its roots in the institution of slavery. The first slave patrol was founded in the Carolina colonies in 1704. These patrols monitored the behavior of Black slaves, returning runaway slaves to their owners and terrorizing slaves into obeying plantation rules. Once slavery was abolished in the United States, the South sought to maintain social order by evolving slave patrols into police units that enforced the Jim Crow segregation laws that restricted Black rights.

Whether to maintain orderly labor for factory production in the North or restricting the rights of Blacks in the South, those in power used local police forces to control the disadvantaged populations, eventually opening the door to crime prevention and community surveillance. Instead of only reacting to crimes, police were given a mandate to stop crime before it happened, leading to the insertion of police presence into everyday life.

While policing has evolved over the years since—police eventually gained uniforms and firearms and shed formal ties with local political wards—the roots of behavior control and community surveillance can still be seen today, especially in historically oppressed communities.

Today, white individuals engage in criminal activity at the same rate as Black individuals: driving over the speed limit, drinking an alcoholic beverage in the park, using an illegal drug, or letting your dog off the leash in a public area. The difference is not in the number of crimes committed, but in the number of crimes observed.

Over their lifetimes, over one in three Black men in America can expect to be incarcerated, versus one in 17 white men. White communities are less frequently surveilled, detained, and violated by police. The over-surveillance and hyper-intervention of police in marginalized communities lead to increased interactions with the criminal justice system.

The effects of these interactions are not restricted to the moment they occur. For every year they are incarcerated, individuals lose on average two years of their life expectancy. Black and brown folks are often arrested for “fitting the description,” low-level quality of life crimes, or for simply being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Laws that prevent previously incarcerated people from accessing housing and jobs increase their likelihood of homelessness and diminish their ability to create wealth. These effects are not restricted to the individual’s life, but have long-lasting consequences for their families and communities.

Meeting Needs Through Mutual Aid

Throughout history, marginalized communities have turned to each other for support when social systems have failed them, or worse, oppressed them. As defined by Dean Spade, a trans activist and lawyer, mutual aid is “about people coming together to meet each other’s basic needs with a shared understanding that the systems we live under are not going meet our needs… It’s a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions.” Furthermore, mutual aid enables those directly impacted by harmful systems to meet their needs and invites them to join the resistance. These groups build solidarity by helping disadvantaged communities design a new relationship to those in power. Or as Dean Spade puts it, mutual aid is more successful and differs from other reform movements because it, “mobilize[s] people, especially those most directly impacted, for ongoing struggle.”

One of the first Black mutual aid groups dates back to 1787, when the Free African Society (FAS) was created to provide support for free Blacks.12 FAS provided housing, food, childcare, and care for the sick in the absence of support from colonial governments that, at best, neglected their needs, and at worst, applied oppressive legal and economic measures against them. The New York Committee of Vigilance would continue the tradition in 1835 by protecting fugitive slaves fleeing state-sanctioned violence in the South, many of whom were not eagerly welcomed or sup-ported by Northern governments.

Mutual aid groups flourished in the 1960s, amidst the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement. The Black Panthers ran 60 social-survival programs, including free ambulance services, medical clinics, and rides for the elderly. One of their most successful programs provided free breakfast to poor children to support them through the school day. These mutual aid groups provided access to basic needs, but also educated and mobilized communities to fight for justice.

And the tradition continues to this day. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the gaping holes in our American social safety net and given rise to numerous community-designed and -led initiatives. Neighbors quickly created mutual-aid groups, restaurants donated meals, people raised money to provide housing to trans folks, and non-Black allies pro-tested alongside Black organizers. In every instance, communities followed a tried and true blueprint of care and creativity.

The Day I Went to Court

On March 26, 2018—though truly it could have been any other day in Brooklyn—a court officer shuffled my partner and me (Stephanie) into the last row of benches, as an arrested person was escorted in by a police officer. The officer freed the man from handcuffs and ordered him to stand next to his public defender at a podium. The prosecutor across the aisle read out the charges: grand larceny, trespassing, and other inaudible alleged crimes that amounted to a bail request of $10,000.

We found ourselves in this courtroom due to a project called Court Watch NYC, which organizes ordinary citizens to observe court proceedings and report what they see. The goal is to hold the legal actors of our criminal justice system accountable to the recent bail reforms. The reforms sought to reduce the high number of people in jail for low-level misdemeanors. Ultimately, the project is designed to protect the communities, namely Black and brown, that have always been disproportionately and unfairly affected by predatory police practices and arrests.

I learned of Court Watch NYC after pivoting my design career into the social jus-tice space. In 2016, I co-founded a nonprofit called Good Call, which ran a free 24/7 arrest-support hotline in New York City. During my time as Good Call’s Director of Design, I increasingly realized that my role as a designer was best served by being an ally, rather than being solution oriented. It was often better to show up and follow the lead of the community members we worked with, or to listen to what the recently arrested needed in the moment.

Neighbors Designing Justice

I volunteered at organizations like Court Watch NYC to learn how to shift my design principles beyond human-centered to com-munity-centered design. Court Watch NYC is just one example of a familiar story: com-munities organizing and embodying the characteristics of mutual aid to protect them-selves from aggressive systems. Just like in the case of mutual aid groups, communities must design their own practices and habits to ensure justice when the legal system incarcerates the innocent.

The CopWatch project run by the Justice Committee in New York City continues a practice started by the Black Panthers in the 1960s, to monitor and document police interactions with the community. The organization also teaches community members about their rights and how to keep their neighborhoods safe.

In New York City, defendants can be assigned a $1 bail for a minor crime, if they have an open case for another more-serious charge. Due to poor communication, families often pay the larger bail, but are unaware of the smaller bail, leaving the defendant needlessly incarcerated without conviction. Created by the Bronx Freedom Fund, the Dollar Bail Brigade is a New York City coalition of more than 1,000 New Yorkers who volunteer to report to city jails and post $1 bails for their neighbors.

Communities United for Police Reform (CPR) is a coalition of community organizations advocating for criminal justice and legislative reform at the municipal and state levels in New York. Designing campaigns, raising awareness, and pushing for policy change, CPR builds solidarity and mobilizes those most directly affected by the criminal justice system to fight for alternatives to policing. Groups such as these strive to dismantle the system from the outside.

Like mutual aids, the people who make up these organizations believe that communities cannot wait for change to come to them, but that they must design the structures they need not only to survive, but to thrive.

On the other hand, organizations like NYC Together work to redesign policing from within the system. In addition to providing support for youth who are arrested, NYC Together aims to build stronger partnerships between youth and local police officers through community dinners, leadership training, and community service projects. By fostering mentoring relationships, NYC Together reduces tension and distrust for police officers while supporting communities’ youth development.

From organizing for policy change to real-locating resources, each one of these groups brings together those who need help and those who can help. Like mutual aids, the people who make up these organizations believe that communities cannot wait for change to come to them, but that they must design the structures they need not only to survive, but to thrive.

Showing Up to Help

Back in the Brooklyn courtroom, after the district attorney requested a $10,000 bail, the public defender laid out the arrested man’s community ties. He had a job at a construction site, a church he attended, and a daughter that he lived with. The public defender requested that the judge carefully consider if the man was truly a flight risk and to release him so he could return to his family and job the next day. Ultimately, the judge refused the district attorney’s bail request and released the man without bail.

As reported by previous court watchers, the presiding judge has ruled without bail often. Many accused are not so lucky. Arraignments before more punitive judges and in courts with a history of unjust rulings end in detention more often than not, resulting in punishment for the accused well before trial or conviction. For many accused, this has meant job loss, disconnection from family and friends at a moment of personal crisis, lack of access to basic health needs or nutrition, and lifelong trauma.

Sitting in the courtroom, jotting down notes about the arraignment proceedings, I under-stood that although my data points are singular, they contributed to a larger shift in thinking about how ordinary citizens can play a role in an otherwise foreign, bureaucratic, and complex system.

As a designer I act as a researcher, facilitator, and a maker. However, in the redesign of policing, designers may need to play a different role. This role is about learning and supporting the communities who have been organizing, leading, and most importantly, persevering through the brutal, oppressive history of policing in America. Designers have the skills and bias toward invention, but the very same skills put us at risk of feeling like the only “solution-makers” in the room. That somehow, our social ills still exist because the right people with the right skills have not yet designed the right solutions.

But if we look to historically oppressed com-munities, we see how wrong that assumption is. We see people who have been fighting and inventing and acting on each other’s behalf for centuries. Community members are constantly designing interventions, working with alternate frameworks, and facilitating conversations that are beyond those taught and used in traditional design toolboxes. Perhaps the designer’s most important role is to show up and contribute to the team. To position our skills of research, facilitation, and making in service of the true experts—the impacted com-munities themselves.

Indeed, designers have skills to contribute to the cause of justice. Inside and outside of institutions, the path to reform is long, and one that is best tackled from all sides. Perhaps it is best not to say, “Here’s what I know,” but to ask the question that neighbors ask each other: “How can I help?”