Futures of Policing

By Default or By Design

In the future, police could use remote technology to peacefully disarm suspects without ever firing a shot. Or perhaps police will use lasers to slice off the legs of even nonviolent offenders. In the future, police forces may expand, but their demographics could reflect the multiculturality of a minority-white America. Or maybe drones will replace police altogether. If they don’t, community gardens potentially will.

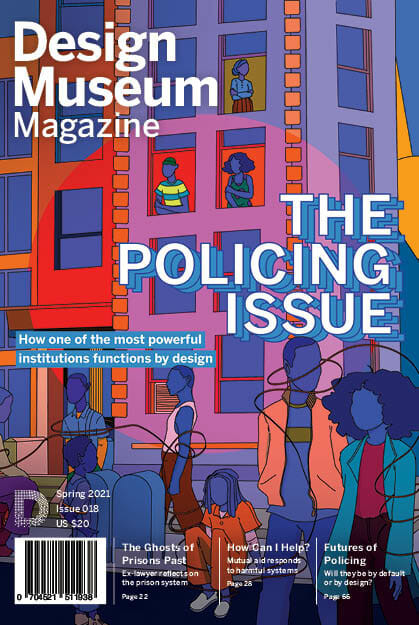

Illustration by Ariel Sinha

By Jamie McGhee

There are as many ways to imagine the future of American policing as there are people living in the country. Some see the United States hurtling toward an unavoidable dystopian crimescape, while others see police systems ripe for abolition. The 2020 protests sparked by George Floyd’s death have proven the criticality of this discussion, as organizers all over the country demand a nationwide interrogation of the police system. Clearly, policing needs to be redesigned. But what will that look like?

To find out, I sat down with organizer DeRay Mckesson of Campaign Zero and storyteller- poet Niki Franco of the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy. I also analyzed the ideas of novelist Sophia Stewart, law professor Bennett Capers, and cartoonist Ezra Clayton Daniels.

Will police exist in the future?

DeRay Mckesson, Organizer

DeRay Mckesson is a co-founder of the police reform movement Campaign Zero, whose 2020 #8CantWait campaign called for policy reforms and drew vocal support from celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey and Lupita Nyong’o.

DeRay cut right to the heart of the matter with the practiced precision that comes from years as an organizer. In the future, will there even be police at all? Or will abolition succeed? According to him, that is the wrong question to ask.

“The question is really not police or no police,” he said. “That is a losing frame. There will always be conflict. The presence of conflict between people is exacerbated by inequity, but it is not always a result of inequity. We can have all the resources we need, and there will still be conflict. So the question becomes, who intervenes in the worst of the conflict? Who intervenes in the worst of the harm? The police are the easiest, simplest, and laziest answer to those questions—not the best.”

While some organizers believe that the police force as we know it needs to be entirely abolished, others suggest that it can be reformed in the short-term. These beliefs are often viewed as mutually exclusive.

“I think it’s actually one of the tricks of white supremacy to make it this battle between reform and abolition,” he said. “One approach says to take it [the police system] down in pieces, and one says to take it down all at one time. I don’t think that’s actually a battle.”

DeRay emphasized that short-term change does not preclude long-term abolition. “As somebody for whom this is not theoretical, I know that there are people who are harmed today, and if I have the power for them to be less harmed, I should use that power,” he said.

Similarly, DeRay noted that the end of solitary confinement is not the end of incarceration, but with the end of solitary confinement, inmates would be moved to another, potentially better part of the jail. “There’s a frame-work that says that’s not abolition, that’s not the end of prisons and jails,” he continued. “Well, it’s like do we end solitary confinement or not? We absolutely do. This is a no-brainer.”

DeRay explained the importance of being deeply engaged in harm reduction, to make sure that all of our strategies are heading in one direction. “People talk about it as if we are walking in two different directions.” DeRay shook his head. “In fighting for the imprisoned to have three solid meals that are nutritious, is that the end of incarceration? It’s not. Is having free phone calls the end of incarceration? It’s not. But is it the right thing to do? Absolutely. And does it get us on the path of undoing the carceral state? It does.”

When it comes to policing, it’s more com-mon to find analyses and criticisms than concrete steps forward. DeRay pointed out that in the social justice space in general, there is infinitely more work around the problem than the solution. DeRay’s own entrance into this particular organizing space informed his adamance about pushing for-ward actionable policies through Campaign Zero. “I didn’t grow up in policing,” he said. “Education was where I started. So I too… [realized], ‘This is bad, let me go see what people are going to do about it.’”

That’s where Campaign Zero organizes from. “We make solutions public. We try to help people understand what you can do. You don’t need to be in some 300-person organizer collective to get access to the information. We’ll never win that way,” he said.

For DeRay, the future hinges on one thing: “The future of policing is a question of, could we organize?”

Will technology make policing more or less violent?

Sophia Stewart, Novelist of Matrix IV (published in 1981 as All Eyes On Me Incorporated)

That “we” DeRay references is a critical facet of change. Who does it include? We non-law enforcement civilians? We designers, educators, and writers? We, a nation of people who believe in the fair exercise of justice?

What is the future, however, if “we” can’t organize, while the American police force is allowed to grow unchecked in power, and technology advances exponentially right alongside it? For science fiction novelist Sophia Stewart, that would be calamitous. Over the past four decades, she has witnessed the police force increasingly evolve to resemble the hyperpoliced dystopias in her fiction.

In her novel Matrix IV, she speculates that advances in technology will soon build devices of surveillance, policing, and penal jus-tice directly into the human body itself. In this future, the prevalence of surveillance technology means that every felony is recorded and punished as soon as it happens. And what is that punishment? In Stewart’s future, prisons have no walls. Instead, they

have rings. Anyone convicted of a crime is microchipped and fitted with rings that intake a steady stream of biometric data while floating around the user’s body. Rigorously tracked, the convicted per-son is allowed back into society to resume their nor-mal lives. The rings serve as an omnipresent police force that metes out violent punishments for perceived re-offenses. If someone is thought to be fleeing the scene of a crime, the rings activate lasers to slice off one or both feet. The crime of murder results in instant decapitation. In a 2017 interview with BMEntertainment, Stewart acknowledged that this technobrutal police state is a dark one, but it is not without precedent. Contemporary stop-and-frisk policies, the use of tasers to subdue suspects, and the rampant tear-gassing of protesters demonstrate the degree to which the state is comfortable giving law enforcement officers the means and mandate to punish civilians extrajudicially and at their own discretion. In Stewart’s speculative narrative, the rings are designed to be race blind—a clear critique of real-life policing—but in her dystopian future, racism continues to inform definitions of criminality. And designers remain complicit with the worst offenders of state-sponsored violence, as they employ the tools of innovation to build newer, better technologies that serve as extensions of state power. None of this happens without design, either in fiction or in real life.

On the other hand, when the demographics of the state change, then the intentions and philosophies guiding policing technology could change too. In sharp contrast to Stewart, one lawyer believes that America’s changing demographics will soon lead to a future scrubbed clean of police violence.

Does policing play a role in Afrofuturism?

Bennett Capers, Law Professor

Fordham Criminal Law Professor Bennett Capers believes that the days of white majority rule are numbered. In 2044, the year when the Census Bureau projects that the white population will become the minority in the U.S., law enforcement technologies created by people of color and funded by a

majority-POC government will bring a decisive end to police brutality. In “Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044,” published in the April 2019 issue of the NYU Law Review, Capers meditates on possible police futures through the lens of Afrofuturism, a philosophy of liberation whose aesthetics are rooted in the African continent. “A core tenet of Afrofuturism,” Capers says, “is that we embrace technology, especially technology that can disrupt hierarchies and contribute a public good.”

Power.

For Capers, Afrofuturism demands the dissolution of hierarchies and the establishment of systems of equity and economic parity. Wealth redistribution is key, as frustration over economic inequality often fuels violent crime. In this future, redistribution accompanies a nationwide effort to de-fetishize capitalism. People begin to view overt wealth as déclassé as social programs make certain markers of luxury redundant—in a world with universal childcare, there is no need for private nannies.

Increasingly diverse courtrooms overturn centuries of American law rooted in white male patriarchal ideals. Virtual reality plays a crucial role in building empathy, allowing everyone from judge to jury to digitally step into the lives of people from all backgrounds.

Narratives.

With a shift in political and judicial power comes a shift in what is criminalized and how crime is punished. Sex work is legalized, meaning that sex workers are no longer forced into dangerous underground situations in order to avoid arrest. The avail-ability of social programs means citizens must no longer make ends meet with malum prohibitum crimes, or actions that are illegal despite lacking intrinsic amorality, such as selling loose cigarettes; furthermore, such actions become legal as well. The War on Drugs meets a swift end. What becomes illegal? Explicit discrimination. Removing a passenger from a plane because of their nationality or even tailing someone through a store because of their race is made actionable on a civil level.

Outcomes.

“Afrofuturists, as utilitarians, will ensure that the punishment, when imposed, serves a public good that exceeds its cost,” Capers says. For example, anyone who commits a violent crime receives psychological treatment and ther-apy, and restorative justice allows the perpe-trator and the survivors of the victim to work together toward resolution.

How does policing look in such a society? Like Stewart, Capers sees hyper-surveil-lance as inevitable, but for him, it’s a benefit. Speaking of the contemporary role of cam-eras in countering police brutality, he says, “Surveillance cameras have functioned as a tool of survival, as a way of making racism and inequality real, as a godsend, and as proof.” He longs therefore for widespread surveillance technology—including not only facial recognition, but also gait and voice recognition—in addition to the collection of DNA from newborns. The constant but equal surveillance of every citizen eliminates the racial disparities inherent to contemporary American policing.

In this world, highly sensitive surveillance equipment can also remotely deactivate suspects’ weapons, thereby eliminating police shootings in “self-defense.” According to Capers, this will result in the elimination of police brutality and racial profiling. This contrasts sharply with the technological land-scape that Stewart lays out, where even non-violent crimes are met with brutal violence. What separates these visions of the future is design: Capers’ technology is optimized to pacify and disarm, while Stewart’s is intended to punish and incapacitate. It is clear that one of the capacities of designers is to consider how to mitigate harm through innovation.

Working within the context of legal reform, Capers offers a window into a near future that asks all of us to do the hard work of changing not just policing, but the social systems and narratives that activate the system. Abolitionists, however, believe that Capers’ ideas for reform do not go far enough and that policing needs to be dismantled entirely.

What will police abolition look like on the ground?

Niki Franco, Poet-Storyteller

Niki Franco is a storyteller, abolitionist, and poet whose work focuses on decolonization, reproductive justice, and systems of power. As an Artist in Residence at the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy, she believes that storytelling is key to envisioning a world without policing.

“Black folks, oppressed people, and pre-colonial societies are societies of storytellers,” Niki said. “Through apocalyptic, horrific moments, we’ve constantly had to practice interrogation, asking ourselves, ‘Okay, hold up. Where do we come from? What are the legacies of care and community support that we come from, and what is not normal?’ Our stories are really good at lifting the veil on things that actually don’t support us, on things that are actually harmful and abusive, and are actually not indigenous to us.”

Storytelling encourages people of color to visualize the future by looking backward and drawing from centuries-old traditions indigenous to West Africa. “We’re in a moment where restorative justice is popping up. These are practices that come from indigenous tribes out of West Africa. We’ve been practicing mediation with our people for a very long time, because it’s nowhere in our historic legacy to have a default mode of disposing of our people, right? We’ve always had a strong value of human life and of community,” she said.

Niki acknowledges that indigenous ideas of restorative justice clash with how popular American media portrays justice. Television shows, movies, and music push revenge fantasies that subconsciously justify a carceral state and a police state.

What is the role of artists in pushing against these narratives? “Storytellers are tasked with not just challenging and cutting through the hegemony of thought, but also offering alternatives,” Niki said. “What we’re dealing with right now is a crisis of imagination. Right now, and not just right now, but at any revolutionary moment in history, cultural workers—be it by way of pamphlets, stories, oral histories, songs, chants, and illustrations—have always had a role in advancing the new ideology.”

“Abolition” and “defunding” may sound like distant goals, but Niki doesn’t agree. “Oh, sometimes we think it’s this big lofty thing. But the core values of abolition are care, are solidarity, are valuing relationships, are relating to the lands in a non-extractive way. And all of us were tasked with negotiating what that meant in our communities this year. Many young, Black, brown, and indigenous folks were just like, ‘Okay, how do we create sup-port systems? How do we create networks of care for one another?’ Sometimes we think it has to be a full revolution. But that won’t hap-pen overnight,” she said.

The reality is that abolition is grounded in the immediate and the attainable—human relationships. “If we want to reorganize our society outside of the punitive state,” Niki said, “then we must develop capacities to actually be in right relationship with each other, even when bad things happen.” Like DeRay, Niki believes that praxis needs to accompany theory, that uniting people and making change in the field is key. “If we are honest about the origins and functionality of policing, life-affirming institutions and policing cannot co-exist in my opinion. Abolition is very clearly demanding almost an entire overhaul of our society as we under-stand it. Workers should absolutely be centered in this transformation. There are really imaginative and creative, beautiful ways in which we want to rebuild. And there are also fundamental structural things that we need to address: Black labor, immigrant labor, and what’s considered unskilled wage labor are the anchors of our economy, which have contributed to the wealthiest nation of human history,” Niki noted.

Television shows, movies and music push revenge fantasies that subconsciously justify a carceral state and a police state.

Despite the U.S.’ wealth, Niki has encountered critics of abolition who believe it isn’t economically attainable. “The constant push-back so many of us receive is, ‘Well, who’s going to pay for that?’ But there’s no historical reason why we should cut ourselves short. Abundance exists but is coalesced for a small percentage, for the elite,” she remarked.

An abolitionist society would provide abundantly for all its people. “We all deserve access to our basic needs,” she said, “and not just shelter, water, food, but as spiritual beings on this earth. We should have access to care, mental health support, the great out-doors. We deserve to exist in the interconnectedness and the expansiveness of the natural world. And we deserve leisure. We deserve rest.”

Everyone does deserve rest. But for organizers like Niki that can be in short supply. “I get really excited and then sometimes I get really overwhelmed,” she said. “Because when I think of this abolitionist future, it’s not just about the cages, the prisons or jails, it’s also about, ‘What does a just economy look like? How do we stop extracting from the earth? How do we stop policing each other?’” One cartoonist in Los Angeles has a few ideas.

How will cities institute abolition?

Ezra Clayton Daniels, Cartoonist

In the June 9, 2020 edition of the online journal The Nib, science fiction cartoonist Ezra Clayton Daniels sketched out the speculative realities that can replace the Los Angeles Police Department by 2023.

The starting point for Daniels is housing every homeless Los Angeles resident. What follows are four proposed agencies that pro-vide essential support services:

• LA Department of Food Security ensures that all residents have free, vitamin-rich food, courtesy of a 100-acre farm that offers volunteers agricultural training in exchange for labor.

• Climate Mitigation Department regulates individual, industrial, and commercial pollution and resource use. In the case of climate catastrophes, such as wildfires, they are the first responders. Jobs created by this department boost the local economy.

• Mental Health Department handles all incidents involving people who require psychiatric specialists. Police precincts are repurposed into short- and long-term mental healthcare facilities.

• Department of Crime Deduction hires detectives of all ages from a variety of backgrounds, selecting people based on creative problem-solving abilities, not seniority within a police force. The increase in diverse perspectives corresponds directly to an uptick in the speed with which cases are solved.

The result? A community that is fed, cared for, and protected. That is the abolitionist dream that organizers like Niki and DeRay advocate for, one in which adequate social and human services mitigate the need for punitive action by the state.

What is the global importance of the American police system?

The future of policing could be a grim one that feeds on violence, or a constructive one that leverages abolition to support local communities. What is clear about American policing is that it’s not just about America.

Niki gravely outlines this at the end of her interview—how the United States chooses to proceed will have global ramifications.

“This is not just an American site. This is not just about dealing with the white supremacist nation space that is the United States,” she said. “It’s actually recognizing that the United States has a very particular positionality in maintaining its military, financial, cultural, and economic influence over the rest of the globe.”

According to Niki, there is hope. “If we’re able to slowly chip away at the beast of these policing mechanisms, we can actually hope-fully see a more peaceful global community over time, a community that doesn’t have the boot of the U.S. on its neck. This isn’t just about Americans and what Black Americans are going through. This is a global struggle. And it’s up to us in the empire to take responsibility,” she said.

As the protests that began in June 2020 continue into the new year, every American—the organizers and the artists, the lawyers, and the novelists—stands at a precipitous moment in history. Designers have many opportunities in this moment to leverage their own skills and the power of a vast community to inform what comes next. The design of narratives that build conversations about what can be. The design of tools that mitigate harm. The defetishization of luxury and a deep commitment to the social sector. And the support of activists on the ground by hearing their calls for change. The future of policing will either happen by default or by design. Which way will the design community choose to go? Which way will the country choose to go?