From Product to Process

Changing How We Use Design in Education

Design education has manifested in many ways, and perhaps it’s time for another turning point. CoDesign Collaborative’s Education Team explores this idea.

Badges like these are a common reward for learners on ed tech platforms. Khan Academy, for example, awards them to students as they complete course content. The online learning platform emerged at the same time that gamification was becoming more popular in education research.

By Mimi Shalf and Josh Kery

Focusing on the end product in education may disconnect your practice from pedagogy. Consider Gamification, which has promised a fun way for educators and designers to engage and motivate learners. The trend popularized design elements like points, badges, and leaderboards before there was research evidence to say how they improved learning outcomes.

As common as gamified elements are in classrooms and in ed tech today, education research is still unclear about which elements are impactful to student learning¹. As a result, educators and designers may want to more closely consider how they choose and use learning theories and design patterns like those used to gamify classrooms.

For practitioners, recognizing that they are producing learning theories and design guidelines in addition to products will help them to evaluate their design choices and better appreciate their design processes.

Background

Design-Based Research (DBR) could be a valuable touchpoint for those looking to rethink their designs’ connections to pedagogy and to popular design patterns. It’s a methodology for conducting research in education, used by labs like the Embodied Design Research Laboratory at UC Berkeley. In DBR, designers iteratively create a design and test its impact on learners. These tests serve to evaluate the designers’ assumptions about how the design affects learners.

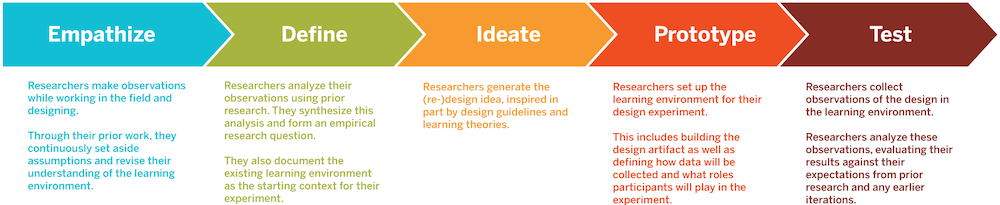

A Comparison of Design-Based Research to the Stanford d.school’s Design Thinking process, which is popular among those designing for education.

Dor Abrahamson, Director of the Embodied Design Research Laboratory, and noted rhyming master², writes that the DBR process produces:

- A design artifact, with documentation of its starting context;

- New or changed learning theories that researchers use to explain their observations;

- Guidelines for other designers to create similar artifacts (also called a design framework or design heuristics) which “cohere” (Abrahamson) with the above learning theories and design artifact.

Bridging Research and Design Practice

We have come up with a set of questions to prompt people to refocus their own practice on their design process, whether they are creating a lesson plan or designing a digital product.

- How is knowledge shared in your professional community?

- Are you talking about your ideas in terms of artifacts, theories, or guidelines?

- How does the change in a learning environment over time and distance alter the way a design can be used?

- When you take inspiration from a theory or guideline, are you considering that difference in context?

We will look at these questions through the lens of the community design center Cambridge D-Lab as a practical example of an approach to design in education.

Case Study

Cambridge Design Lab is a participatory design lab where educators, administrators, and school leaders can learn about design and work on self-identified challenges. It was founded in 2016 by Angie UyHam, a design coach and educator, and is supported both by Angie and her colleague, Khari Milner, Co-Director at the Cambridge Agenda for Children.

At the D-Lab, the most important outcome is that participants add design as another tool to their toolbox. At the start of every project, group members work together to define a “design framework” for the project, in the shape of three images that represent the goals and qualities that will guide them during the process. We will be using the D-Lab as a model to help us think through our guiding questions.

At the D-Lab, images were used to represent the guiding principles of a group’s design work. Pictured: An example of Angie’s design framework: eyes (awareness + learning), head (interpret + brainstorm), and hands (prototype + improve).

1. How is knowledge shared in your professional community?

At the D-Lab, projects are presented in the form of storytelling and videos. Groups craft the story of their process to share with the community and save for later reference. Some projects have even gone on to be published or picked up by local university labs. Furthermore, some members who have finished their project will rejoin new cohorts and bring their knowledge of past projects with them.

The D-Lab isn’t the only lab that has created an ecosystem of knowledge in this way. The research community similarly shares their results and builds off of each other’s findings. Most interestingly, DBR shares their design frameworks as a sort of research pedagogy, consisting of the guidelines used to lead the process and the main takeaways from the project.

In both cases, the emphasis is on the project as a whole, not a single part. Knowledge is not talked about in terms of theory or artifact or heuristic but in terms of theory and artifact and heuristic. The major encompasser of all three is the process—each segment is embedded into some stage (or multiple stages) within the process that has been produced by the project.

2. How does the change in a learning environment over time and distance alter the way a design can be used?

Like with the example of gamification, sometimes the usage gets ahead of the research, but falls behind the times.

The most remarkable thing about the Cambridge D-Lab is their use of participatory design. Participants are taught that their main audience will always be the lead designers of a project. If the project’s focus is kindergarteners, then the kindergarteners are the lead designers and their input is the most highly valued. This requires the project to be deeply embedded in the environment it is working in, and for the designers to be wary of theories and guidelines that push potentially archaic assumptions onto the design.

Participatory design is not unique to D-Lab. It is used in many areas, including equity-based design and DBR. Its biggest benefit is that it makes understanding the environment and the people in it an essential part of the design. This makes designers more closely consider how to involve the environment in their design process, and thus work in the current context, rather than with assumptions from past contexts.

Final Thoughts

Our main takeaway from D-Lab is that it’s all about the process. By focusing on the process, you are encouraged to widen your perspective past your end artifact to include details like your guidelines, considerations, and precedent research. Sharing and documenting processes can help people both to learn how to come up with more great ideas and to better understand the impact of project results. Change may not always be immediate, but it is always possible with the support of a community that creates and shares all of its iterations, artifacts, frameworks, and processes with the world.

Footnotes

1. From Sailer, M. and L. Homner’s meta-analysis of gamification papers: “The large numbers of inconclusive studies in these reviews [26 out of 51] point toward a general problem: Gamification research lacks methodological rigor.” This problem has made it difficult to conclusively moderate for different factors, like collaboration or competition elements in gamified learning, and evaluate their impact.

2. On whether Design-Based Researchers are doing research for today’s students or tomorrow’s, Dor said to us, “Are you [a researcher] thinking about, as Seymour Papert said, what will be someday? Or what will be Monday?”