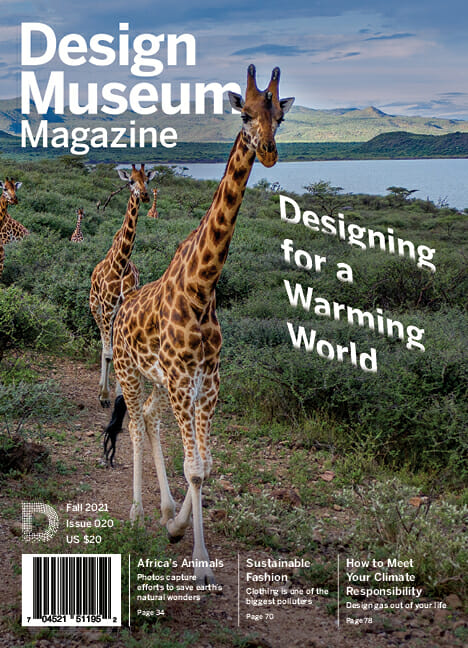

Modeling the Future

How SPACE10’s SolarVille project is lighting the path to democratized access to clean energy

Photo by Irina Boersma, Courtesy of Space10

By Susan Gladwin, Climate Tech Business Leader and Sustainability Strategist

The moment I laid eyes on SolarVille, (1) I fell in love. It brought back the enchantment cast by childhood train sets, a toy that lets us design a miniature world that sets things in motion.

SolarVille is a little wooden village, in perfect 1:50 scale, with the tiniest working, roof-mounted solar panels generating renewable electricity powered sunlight that lights up tiny light bulbs in each of its 20 different kinds of dwellings. In short, it’s really cute. Most amazingly, it automatically facilitates energy sharing between neighboring households. Through the connections of wires and blockchain technology, homes that don’t have panels and aren’t producing any energy automatically “purchase” from houses that have extra energy to share.

SolarVille makes the abstract idea of a “self-sufficient community-driven microgrid” (2) real. It shows us what the concept would look and act like by making it as powerfully evocative as a toy.

SolarVille was made in 2019, but the concept has so far been implemented for big people in only a few places on the planet. But it could be part of how we meet our energy needs–and needs to be. Emissions from our residential lifestyles are set to double, as more people use appliances and other machines for heating and cooling, let alone chargers for electric vehicles. And with energy used in buildings producing as much as 40% (3) of global greenhouse gas emissions, it needs to come from electricity that is powered by clean renewable sources like solar, wind, or geothermal.

When it comes to the climate crisis, energy is only one slice of the greenhouse gas emissions pie. And solarized electricity is only one of the many climate tech strategies being deployed to reduce emissions. Greentown Labs, a US-based climate tech startup incubator, defines climate tech as two types of technological solutions. Those focused on mitigation reduce greenhouse gas emissions and thereby prevent future increases in global temperature that cause the climate crisis, while adaptation solutions build up resiliency to the disruptive and destructive effects of changes to climate.

Climate tech is about people, communities, and infrastructure. It spans how we eat and grow food, shelter and cook, move ourselves and our things, and use and replenish resources of all kinds, in the context of equitable climate restoration. Done well, climate tech solutions consider our interactions within the spheres and cycles of land and sky, water and energy, and how these can invigorate local livelihoods and species survivability.

SolarVille is a project of SPACE10, an independent research and design lab that develops concepts to challenge and inspire its sole funder, IKEA. Together with outside collaborators, the team at SPACE10 ignited an exploration of the democratization of clean energy, asking how clean energy might be made more accessible, more affordable.

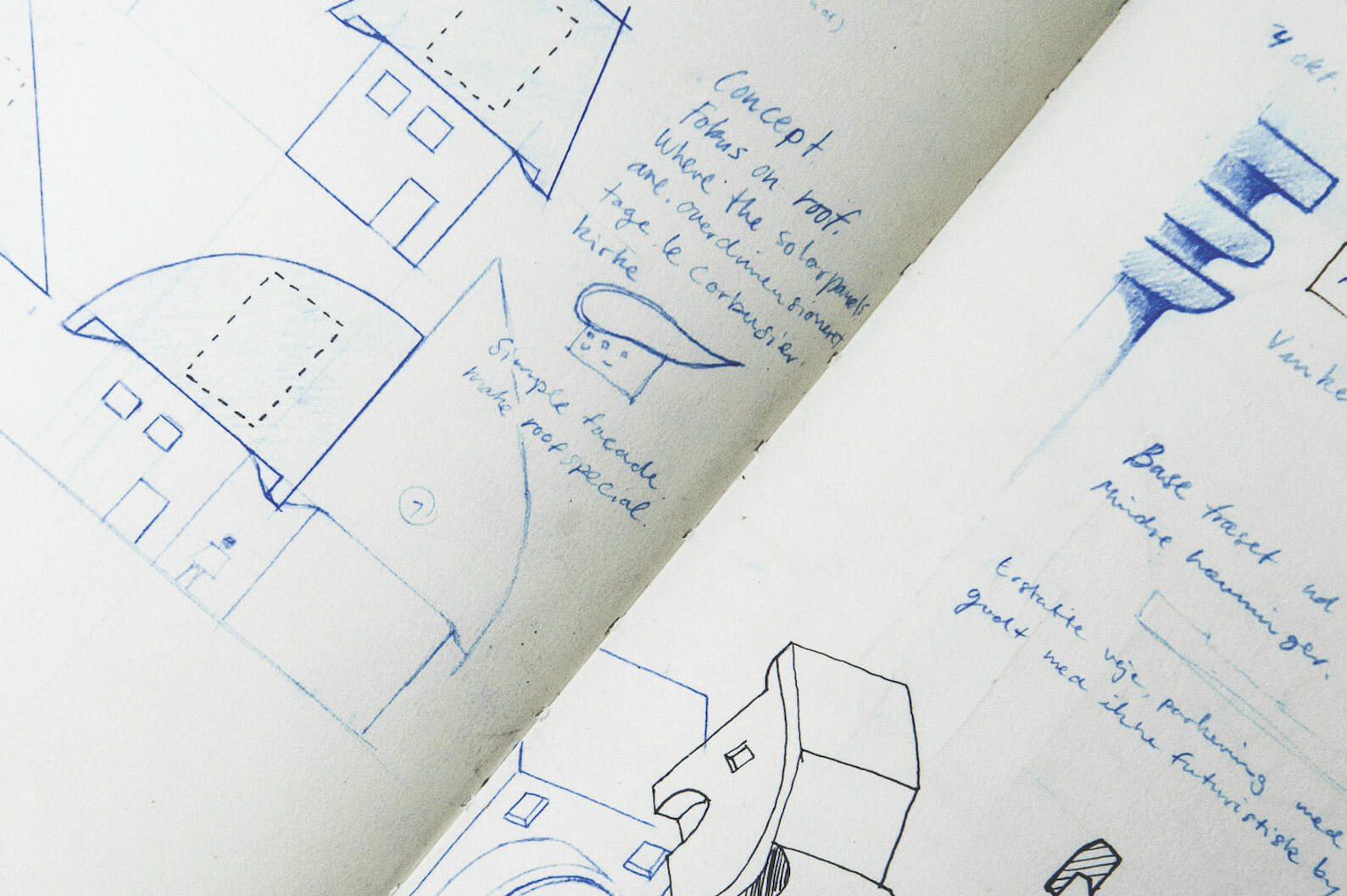

Photo by Irina Boersma, Courtesy of Space10

They focused on demonstrating a decentralized and democratized future of energy systems based on peer-to-peer energy trading networks, which, while a powerful solution domain, is not immediately obvious to diverse audiences such as policy makers, decision makers, and citizens of all kinds. There is power in seeing a complex system in action, but what if it doesn’t exist yet?

Done well, climate tech solutions consider our interactions within the spheres and cycles of land and sky, water and energy, and how these can invigorate local livelihoods and species survivability.

That’s where playful research comes in. “Playful research is an approach, where we translate valuable insights into visions of better tomorrows. Taking research and making it visual to render it more engaging, exciting, and accessible,” explained Mitsuko Sato, Head of Creative for SPACE10.

The making of SolarVille was underway when solar engineer Neel Tamhane joined SPACE10 as Solar Strategy Lead. Neel was already trying to realize the concept of SolarVille in Bangladeshi households through a social enterprise called SOLshare. Neel started at the New Delhi SPACE10 satellite office in his home country of India; the Copenhagen headquarters needed him to bring hands-on working innovation grounded in local context into the clean energy conversation they were catalyzing.

In India alone, over 300 million people are without electricity. Prior to SOLshare, Neel worked on a project in partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation to set up 300 mini-grids in four states in India, converting diesel-powered telecom towers to solar to circulate electricity to villages and marketplaces and bridge between them to the national grid.

“You can build and implement new ideas more easily in places like Bangladesh and India that you can’t in the US. The difference in context and the pressing need enabled us to build new systems, experiment, and bring energy access to many households,” says Neel.

It’s proving to be easier to build SolarVilles in the global South than the North. “While the global North has to transition existing energy systems, the global South is looking at parity for energy access,” notes Neel.

Photo by Nikolaj Rohde, Courtesy of Space10

The brief of our climate design challenge is daunting. But seeing an intuitive solution like SolarVille come to life brings joy and inspiration to engage.

Similar to the mobile phone leapfrog in telecommunications made by developing countries, the global South can jump straight to providing clean electricity for the 3.5 billion people (4) who lack access to it, without the restrictions created by existing infrastructure and all that goes with it. And as Neel points out, “Being able to turn on a couple lightbulbs is an outdated story.” Energy needs and expectations have evolved over the decades, as is spelled out by SPACE10 in this compelling study (5) of 40 families in Peru, Kenya, India, and Indonesia. Neel says, “Governments aren’t looking at only extending utility lines but also setting up integrated electrification pathways (6) within communities.”

This has huge implications for our collective energy and climate future. The global South needs to leapfrog to electricity that is clean so that its citizens can enjoy its health, economic, educational and safety benefits; but as the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, the global North must shift to renewable energy as fast as possible. Neel emphasizes the magnitude of the problem. “Forty percent of the world’s emissions still come from the US. Each American consumes 34 times more energy than a resident of India or China. (7) We need to go all out everywhere.”

Photo by Nikolaj Rohde, Courtesy of Space10

The brief of our climate design challenge is daunting. But seeing an intuitive solution like SolarVille come to life brings joy and inspiration to engage. Neel comments on watching people interacting with SolarVille play. “Ten-year-olds run around trying to figure it out. You can lift a house, cover a panel to stop it from generating electricity, then see other houses start selling faster to it. You see the beauty of watching these little houses trade energy between themselves.”

SolarVille has been on the road, taken to the UN Habitat Center in Nairobi, Kenya8 and to the SPACE10 office in New Delhi. Neel says, “Engaging people with SolarVille is how we can move from design innovation of a novel concept that stops there to something real, activating the policy changes and the capital flow necessary to drive implementation of it.” Seeing SolarVille in action, utilities around the world have started piloting systems like it. As playful as it is, SolarVille shows us the power of climate tech design to animate and realize complex nested systems, from one home, to a neighborhood, to an empowered climate-positive world.

- https://SPACE10.com/solarville-democratising-access-to-clean-energy

- https://SPACE10.com/project/solarville

- https://www.theclimategroup.org/built-environment

- https://www.energyforgrowth.org/memo/3-5-billion-people-lack-reliable-power

- https://space10.com/project/life-without-energy

- https://www.seforall.org/interventions/electricity-for-all-in-africa/integrated-electrification-pathways

- https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2015/12/08/458917881/india-to-u-s-cut-back-on-your-consumption

- https://unhabitat.org/story-solarville