The difference that government design makes in the lives of people

By Dana Chisnell, Civic and Policy Designer

In June of 2020, Julie told a researcher—who was studying the experience

of applying for unemployment in a pandemic—that she and her partner had between 3 and 6 months worth of savings. They were worried about how long they would be able to pay their rent without income from work.

Julie had a pet-sitting business, and her partner had worked as a mechanic at an amusement park for years. But now there were no pets to take care of and no one was going to amusement parks. They had no idea how long this situation would last. The pandemic unemployment story threads together some of the dominant challenges to design in government, as well as what makes doing design in government so great. I see the difference that design makes in the lives of the people I serve every single day, in both large and small ways. Doing design in government actually makes me optimistic. Government services simply have to work. When they do work well, it’s because design made a difference.

We all need government services. Government is irreplaceable.

Julie and her partner were both out of work. There was no work to be had. They needed help. Julie had struggled with health related unemployment and disability for years before the pandemic. She’d been diagnosed with Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID). With this immune disorder, she was more vulnerable than ever during a pandemic. Her partner had never applied for unemployment before, but Julie had. So she applied for disability for herself, and took on applying for unemployment for her partner.

As a small business owner, Julie was eligible for the Paycheck Protection Plan (PPP) offered through the U.S. federal Small Business Administration (SBA). The program was complicated to apply for, and she wasn’t sure that she could meet the conditions of the potential loan. In addition, using PPP to cover wages for her pet-sitting staff would pay them less than what they could get by claiming Pandemic Unemployment benefits. She wondered if she should bother with the loan if her workers could do better by other means.

People come to government to get help when they have needs that they can’t meet otherwise. They’re sometimes in distress, and often stressed when they do come to government for help or other services. Taking the context into account is a key reason to have designers in government: we can help close the gap between the front office and what is happening for real people in the real world through design research. If the unemployment system was designed to meet Julie’s needs, it would remove the load of learning government programs. She shouldn’t have to learn how government is organized – especially while under emotional, psychological, and financial stress. Design could have helped make the program easier to find, understand, and navigate.

Government service ecosystems are large, complex, and difficult for the public to navigate

As designed in the laws that created pandemic response programs, the idea was that the needs of workers like Julie would be met in a new federal program for people who worked as contractors or gig workers. These are jobs that typically don’t pay into the existing unemployment insurance system. In this new pandemic program, the federal government would fund the payments for people like Julie.

But it wasn’t as simple as updating existing forms for the new programs. Yes, the forms needed to make it possible for people to apply who might be newly eligible because of new programs. People also had to learn that they were eligible (many for the first time in their working lives), usually from state government websites. They had to learn where to go to apply, then set up an account, and file the form. They had to support their application with evidence of their previous income, and verify their identity.

Of the 33 people like Julie who told the researchers about their experiences, not one said that the unemployment website where they filed their claims was easy to use. And filing the claim was just the beginning. Several participants reported that tracking their claim, verifying their identity, and correcting mistakes became their new full time job as they waited weeks or months for the first payment to arrive in their bank account.

In government, solutions – services – are sliced up in ways that make it difficult to identify who owns the problem. How these programs get delivered comes back to dozens of design decisions. Decisions made by government officials who are all trying to meet the challenges of the moment. But the services and the ecosystems they exist in are huge. They’re complex. And if not designed to meet the public where it is, the services can be difficult to navigate. The design decisions made by lawmakers, regulators, and program implementers made a difference in Julie’s access to unemployment payments. One of the most challenging aspects of meeting Julie’s needs was time. Could the government implement new programs and process her application before Julie’s savings ran out and as the pandemic wore on?

The time scale and pace of designing and delivering government services is different from private sector products, often for good reasons

Julie said that she and her partner had about 3 months’ worth of savings. In June of 2020, no one knew that the pandemic would last for a couple of years. Spinning up new services usually takes years in government, no matter what level you’re working in. To spin up new services within a few weeks—or even a few months—is a challenge that few government agencies could pull off. There are updates to systems, yes. But the challenges start far upstream from there.

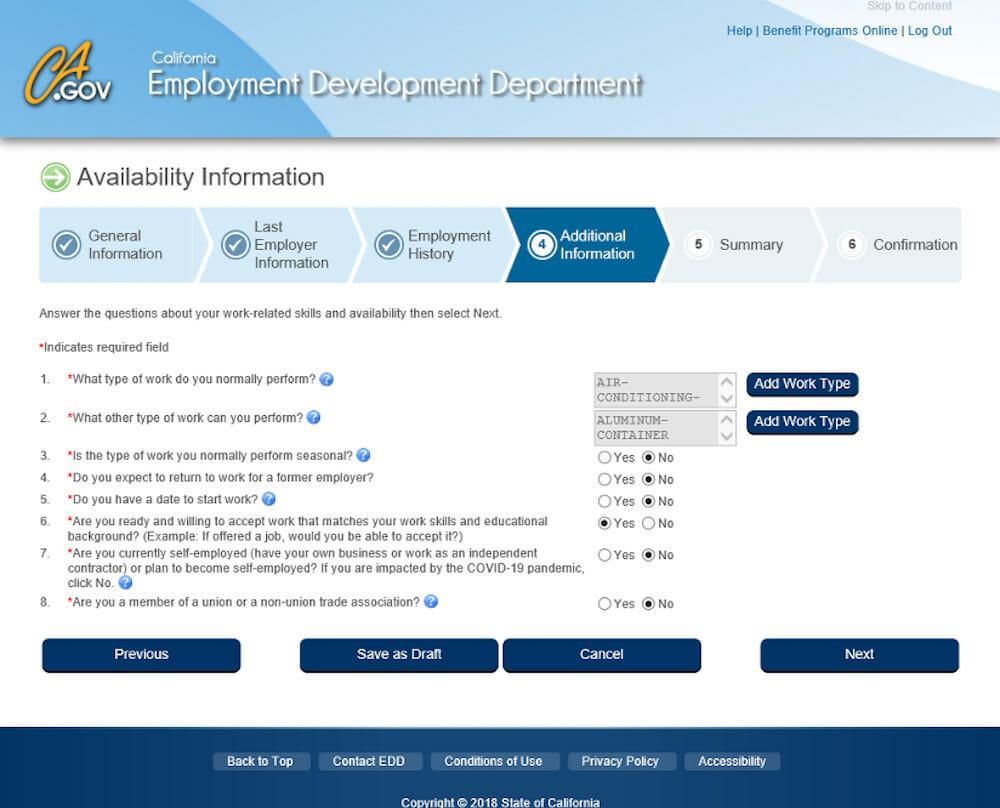

UI Online, the California Employment Development Department webapp incorporated fields for pandemic unemployment in April 2020

There’s a stereotype that government can’t do certain things well or that it lags behind the private sector in its design and delivery of services. There’s an implied dynamic of the private sector being better at these things, somehow. But there’s an argument to be made that the cautious consideration of the needs of the public and the responsibilities to taxpayers are exactly the type of design constraints you want on public services. To deliver services in ways that protect taxpayer interests and beneficiaries, government errs on the side of resilience and long term sustainability of programs, rather than efficiency and speed. Throwing an experiment into “the market” to see if it works when “the market” is underserved and vulnerable is unethical and irresponsible. “Fail fast” doesn’t work when failing means that someone doesn’t get a service or a benefit that helps them stay housed, fed, and healthy.

Data from design practices like user research and usability testing help mitigate risks of service failures. It’s worth the time to get data from these practices, because they can inform design decisions and problem definitions. When problems are well defined, it’s easier to design solutions that positively affect the efficiency and speed of delivery of services. When services work well, people like Julie perceive that, and are more likely to trust government services, even if they aren’t delivered on a tech sector timeline.

“The boulders we choose to push are huge and half buried in the dirt. It takes a lot of leverage to move them.” — Harlan Weber

Government services must serve everyone at every intersection of their lives, especially when the stakes are high

Government services must be designed for literally everyone. In the worst of times, government services must work well for everyone while they are distressed, desperate, and exhausted. The stories from the study that Julie was in revealed complexities and intersections of real, human lives. Design offers methods and techniques for addressing realistic life challenges that the public naturally brings with them when they interact with government services.

For example, people like Julie were unemployed (with no prospects because everything was shut down) and afraid of losing their homes. Others in the study were taking care of others who might or might not be sick, homeschooling their kids, and/or dealing with shortages of food and staples. Several of the participants in the study that Julie was in had experienced the death of a friend or a family member from COVID-19 or other causes in the weeks before their interview. People were suffering, and they took that struggle with them as cognitive load when they applied for unemployment.

This is a level of severity that many of the designers I talked with for this article hadn’t considered much before they went to work in public service. In their private sector jobs, they could assume that the user of their catering app or the e-commerce site or the music delivery app, or meditation app or the investment site they worked on were reasonably affluent, educated, and unflustered. (Healthcare is one notable exception.) The products and services they’d worked on before generally were not high stakes. They didn’t have to consider people with low vision or blindness, who were hard of hearing or deaf, had mobility or dexterity issues. They didn’t have to think much about whether their own privilege and biases and assumptions about the world were going to harm someone. Not considering these factors is also a set of design decisions. (And wouldn’t it be great if every designer did come to work with all of this as part of their practice?)

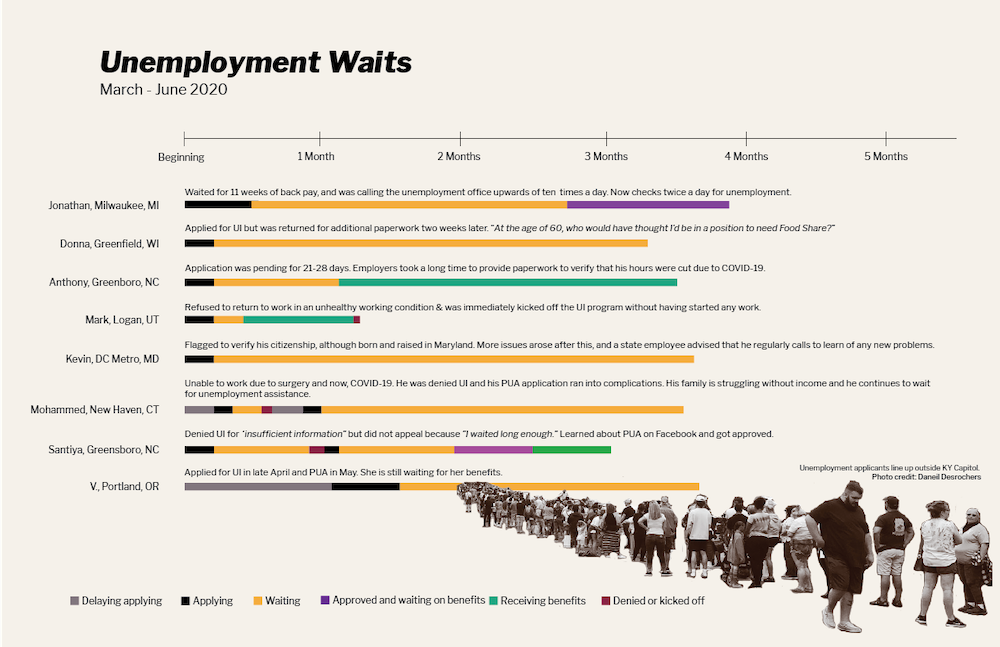

llustration showing wait times for participants in a research study, March – June 2020.

Government serves individuals but people operate in relationships

Julie’s story – and the stories of others – showed the researchers that the way people experienced interacting with government was not as a lone person. Julie applied for her partner. Others in the study helped parents, children, or siblings. The benefits available in the service ecosystem beyond unemployment payments could depend on how many people were in the household, how much income or savings they have, ages, abilities, and needs. As Julie and her partner navigated unemployment claims, they were also trying to use other government programs at the same time. But there isn’t a one-stop shop where someone could say, “Hey, I’m struggling, what help can I get.” While government services exist in vast ecosystems, every applicant is also a member of familial, social, and geographic webs of relationships. Designing benefit programs that see people like Julie as whole persons who exist in relationships with histories and futures would help her survive in the short term and thrive post-crisis.

Designing for massive numbers of people in need

Julie was among 33 participants in the study. But the scale of need across the U.S. was enormous—far greater than at any time since the Great Depression in the 1930s, when 12.8 million people were out of work.

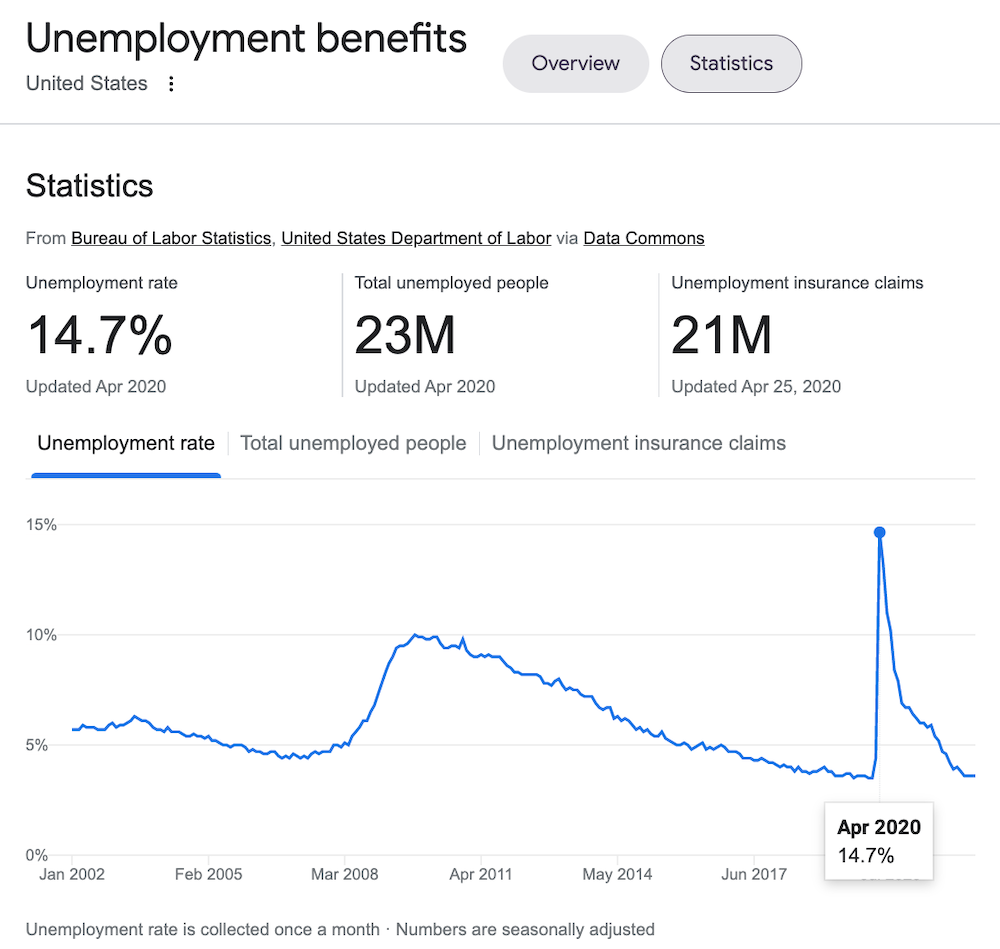

In the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit hard in the United States and around the world. In the U.S., in April of 2020, the unemployment rate was 14.7%. About 21 million people applied for unemployment that month. At least another 2 million were without work but had not filed an unemployment claim.1 21 million users doesn’t seem like a lot compared to the scale of some private sector digital services. For example, as of March 2022, Facebook claimed nearly 180 million users in the U.S., and 2.9 billion worldwide. TikTok has 1 billion users. Amazon claims that more than 197 million people shop on their site every month.

But unemployment claims give us a lagging indicator for the health of the economy. We want that number to be low. While U.S. unemployment was 14.7% in April of 2020, it had been only 3.6% in December of 2019. It stayed pretty close to that through March 2020, and then spiked in April. Imagine scaling your business from 5.8 million users in January to 23 million in April. It might be the kind of growth that tech companies dream of, but even the best run state government programs in the best of times could not come close to scaling that much that fast.

To manage that kind of growth and implement new programs, quickly, was a challenge unlike any other that anyone working in government had ever encountered. As Cyd Harrell pointed out to me, “The service complexity and the stakes are also much higher [than for private sector tech companies]. Facebook isn’t adjudicating whether people have properly verified income.”

Julie’s experience of encountering confusing programs that were difficult to navigate was shared by tens of millions of other people in the summer of 2020. Many of those people were in deep need. Design could have helped program implementers understand and anticipate what that level of need —combined with a complexity of programs—would mean for customer service, case management, and making decisions on who to pay and how much to pay them.

“Having a pulse on what the lived experience is like and having access to the levels making decisions is important to closing the gap” — Sha Hwang

The power imbalance is bonkers

A key role in government services is that of the person who makes the decision about whether and how much of a benefit a member of the public gets. Let’s call that person an adjudicator. They might be a TSA officer, or an account manager at the Social Security Administration, or a claims approver at the Department of Veterans Affairs. They could be an immigration officer, or the person who determines your eligibility for Medicaid, a SNAP application, or unemployment payments.

Generally, these public servants are highly trained, care about the mission, care about the people they serve, and are deeply professional. But they also hold power. And, yes, some hoard it. But even if the adjudicator is one of the best humans on Earth, the applicant may feel they are at the mercy of someone who could just be having a bad day (or a good one). That feeling is valid, even if the systems are set up to prevent individual adjudicators from making judgements that are inappropriate. Policies, which are design decisions, can also create incentives for adjudicators to behave the way they do. Everything does come back to incentives, and people do what they get rewarded for.

But power is also a factor that designers in government must deal with. They have it, simply by virtue of their position in government. If you don’t think this creates an effect in research interviews and usability tests, I challenge you to think again.

Designers must also design for adjudicators—to make it possible for them to enforce the laws and policies while still bringing their humanity and expertise into the interaction. Say Julie got through to an unemployment adjudicator on the phone to correct a mistake or check the status of her application. That touchpoint between applicant and adjudicator is designed. Can it be designed to be satisfying for Julie without compromising the adjudicator’s efficiency and priorities to prevent fraud? These are huge customer service challenges.

Listening to speeches during a naturalization ceremony at the Boston Federal Courthouse on July 4, 2015.

The hardest job I have ever loved

I’ve worked in several policy areas in government, from election administration to safety net programs, to immigration. For a couple of years, I worked on helping a federal agency called U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to transform its services from all paper to all digital (this is still a work in progress). I’d seen all the steps of several immigration processes from the inside. It was time to see the fruits of my labor.

One day, my spouse and I trotted down to the federal courthouse in Boston. We were there to see a naturalization ceremony. There were about 100 people there, holding little American flags, dressed up, many of them accompanied by family members or friends. There was a speech by the USCIS district director, and then a judge came out. The judge asked everyone to stand up and raise their right hand and repeat the words of an oath that would complete their journey to become a citizen of the U.S. It was one of the most profound experiences I’ve ever had. People were wiping away tears. I was one of them.

I hope these new citizens have experienced only the best that government has to offer: safety, health, and support of various kinds when it is needed. I hope that some will work in public service to make life better and more hopeful for others. Because that’s the gift I receive every day as a designer in government – hope.

Working in government makes me optimistic. Even when the work feels deeply frustrating, agonizingly slow, and mired in bureaucracy. And especially when I have the privilege of working on something that is emergent, urgent, or a crisis. Change happens in increments over time. As I said, I see the difference that design makes in the lives of the people I serve every single day, in both large and small ways. Everyone should do public service, at least for a while. It may be the hardest job you will ever love.