Designing in Blue

How IBM Adopted Design at Scale

I’m sitting in a conference room in IBM’s office in Cambridge, MA, on a video call with my team. We’re doing a playback, that’s what we call a collaborative user experience review, with IBM’s Head of Strategy, our Chief Digital Officer, and two senior managers with hugely important missions for our company.

By Charlie Hill, IBM Fellow; Photos and renderings from IBM

I’m stepping through some low-fidelity wireframes, our first take on a new platform we’re developing. It’s early days and we’ve barely started the design work. I ask them to focus their feedback on the basic user flows, and not to pay too much attention to the UI details yet. The playback goes well, but that’s not to say they love everything we showed them. Our head of strategy has questions about a class of users we haven’t included in this work, and our Chief Digital Officer tells us we left out a critical idea about community engagement. So, we have lots more work to do – and that’s the point. When we hold playbacks like this, whether within our team, with stakeholders, or with our target users, it helps everyone focus on the quality of the user experience that we will bring to market. It helps us as a team learn faster and execute better.

Design Gap

IBM is one of the largest technology services companies in the world, and one of the largest software vendors. Even if you never see an IBM logo, you can be sure that many of the services you use every day run on IBM platforms and technologies. Back in the 1960s, IBM developed a pioneering corporate design program based on the principle that, as IBM CEO Thomas Watson Jr. said in 1973, “good design is good business.”

However, decades later, a substantial “design gap” had emerged at IBM. A few years ago, playbacks such as the one I described would not have happened. Back then, in many teams, user experience took a back seat to almost everything else. Aside from a few pockets of design, many teams lacked even a single dedicated designer. Rather than consider user outcomes, many business leaders tracked their teams’ progress using project management charts and feature lists. This design gap posed a serious problem as teams increasingly looked to cloud and mobile technologies to better solve our clients’ problems. By establishing a more direct and even intimate connection with users, these technologies make it possible to create more engaging and “frictionless” user experiences. As a result, design takes on an increasing role in delivering successful outcomes.

Today, as a result of a program we call IBM Design, things are very different. Playbacks are a routine part of how teams work and how managers interact with their teams. Most teams are appropriately staffed with highly skilled, formally trained designers who work alongside product leaders and engineers. As teams measure their progress, they pay close and continuous attention to user experience. We’re well on our way to closing the design gap that we saw when we started.

Big Blue, Big Change

How does one even begin to change a company with many different business units, hundreds of thousands of employees, and operations in more than 170 countries? I’m part of a team that first came together in the second half of 2012 and took on the mission to establish a sustainable culture of design at IBM. Some of the key ideas behind IBM’s design program were there from the beginning, but changing the culture and behaviors of such a large organization required more than a blueprint. When we launched our program in January 2013, we didn’t know what was possible or what tactics would work. In fact, although we believed strongly that design was essential to IBM’s future, we were unsure whether changing a company with the size, complexity, and global footprint of IBM was even possible.

The journey started for me in early 2012 when I met Phil Gilbert, two years after his company, Lombardi Software had been acquired by IBM. I am a designer by trade, and I previously designed a number of collaboration tools. Since joining IBM, Phil had great success simplifying another part of our software business, and the idea had emerged that he might be able to bring his approach to the larger organization. I met Phil when we were both asked to talk with the executives running IBM’s software business about how to improve the design of our products. At that meeting, I immediately recognized that Phil was a rare executive who not only understood design deeply, but, even more importantly, was also an exceptional leader. I told him as much as we left the meeting, and I added that if he could win backing for a new design initiative, he could count on me to help him make it happen. I told him that even if we didn’t agree on every detail, his leadership would make all the difference, and I would give him my full support.

At that same meeting, Phil had already identified a very basic problem, the lack of designers on many teams. He proposed that, as a rule of thumb, every product team should have, on average, one designer for every eight developers writing code. Having previously been the sole designer on a high-performing team of about eight developers, this made sense to me. In fact, it felt like a minimum benchmark. This target skills ratio proved to be a powerful organizing idea. It made the scale of the problem immediately clear: it was obvious that it would take several years to fill the gap. At the same time, it allowed an incremental approach where we could focus initially on getting a few teams enabled with the right skills. If that worked, we could scale up to more teams over time. The ability to articulate a view of the overall target state, combined with a focus on delivering meaningful outcomes right from the start, framed our initial approach.

Within a few months, I found myself reporting to Phil, leading part of a small team funded to hire more than a hundred designers in the first year. But, we knew that hiring designers would only get us so far. We wanted to integrate them with existing teams, rather than create some sort of “innovation lab” off on the side that might do fabulous things but would leave the existing culture largely untouched, if not downright alienated. As we thought about bringing the most creative and effective designers we could find onto these existing teams, we knew there was another big challenge ahead of us. Unless those teams embraced design, the designers would be left on the sidelines, and would probably quit. Our program would fizzle before it got off the ground. We needed not only to bring in designers, but also transform the values, mental models, and practices of our development teams so that they would fully embrace design and take on faster, more creative ways of framing and solving problems.

Design Thinking at Scale

To do this, we decided to bring design thinking into IBM – a set of practices that had emerged over a couple of decades and were already popular in design agencies and academia. However, those practices were very focused on small teams, and largely untested in large software development organizations. Based on Phil’s previous experiences leading large teams, we created a new framework that we now call Enterprise Design Thinking. Our framework promotes design thinking, but introduces three “Key Practices” that help teams apply design thinking in a more scalable way: Playbacks; Sponsor Users (users we recruit to participate in the design process); and Hills (a way of defining project milestones in terms of user outcomes).

Even before we had hired our first batch of new designers, we had already engaged with a few teams. And yet, despite some great collaboration with those teams, it was hard going. We realized that certain initial conditions needed to be met for teams to have a chance of successfully adopting a new level of design capability. With our first new hires coming on board, we started to work with business unit leaders to identify the teams that they most wanted to invest in to drive their business. We onboarded these teams into a program we developed called the Hallmark Program, with the condition that their executive leaders be willing to commit adequate resources and meet certain other entry requirements. The Hallmark Program then gave these teams exclusive access to a powerful set of resources including new design hires, an immersive bootcamp for adopting Enterprise Design Thinking, and new studio space in which to work in a more open collaborative way. The Hallmark Program became the engine of our entire initiative over the next three years, and enabled us to scale up from a few teams to around a hundred large projects in that time, on the order of 10,000 people.

Meanwhile, we were hiring designers – lots of them. We paid attention not only to a candidate’s design skills, but to their leadership qualities too. From the start, we knew that hiring wasn’t enough. We wanted to establish a new class of leader at IBM. We believed that designers, with their human-centric values, their different way of thinking, and their mastery of design craft, could transform not only our teams, but also our company’s leadership culture.

Having hired so many designers, we worked hard (as we continue to do today) to give them opportunities to prove themselves as leaders, advance into more influential positions, and take a seat at the table alongside the most respected engineers and product leaders. We created a dedicated career path for designers at IBM, all the way up to VP on the management track, and all the way up to IBM Fellow on the technical track. We set up a coaching program for diverse design leaders to ensure that our senior design leadership reflects the impressive diversity of our overall population of designers. It’s gratifying to be at a point where we can now see designers who joined IBM over the past few years taking on some very big missions and the kinds of leadership roles we originally envisioned for them.

IBM Design

Things are very different now from when we started. I have the privilege to work with exceptional designers every day, ranging from talented and ambitious early-career professionals to seasoned senior designers and executives. They are at work all over our large company, and they represent many disciplines such as design research and service design, visual design and typography, user experience design, content design, accessibility, and front- end development. We work together to define the leadership qualities and skills we most value, and make joint decisions about senior appointments. When we combine our diverse disciplines and experiences, it makes us all smarter and enriches our culture.

At the project level, we’ve moved on from the Hallmark Program. Every business unit now has a design management structure, typically headed by a VP or director of design who is allied with a senior business unit executive. Our designers sit within the business units under these leaders. As a result, design is now largely embedded and empowered within the business units, our corporate brand and marketing organization, and our client services teams.

The studios that we built around the world provide great collaborative spaces for our designers and multidisciplinary teams, but, more importantly, they also enable our teams to engage customers and stakeholders in active work sessions, helping to develop ideas and make shared decisions faster than ever.

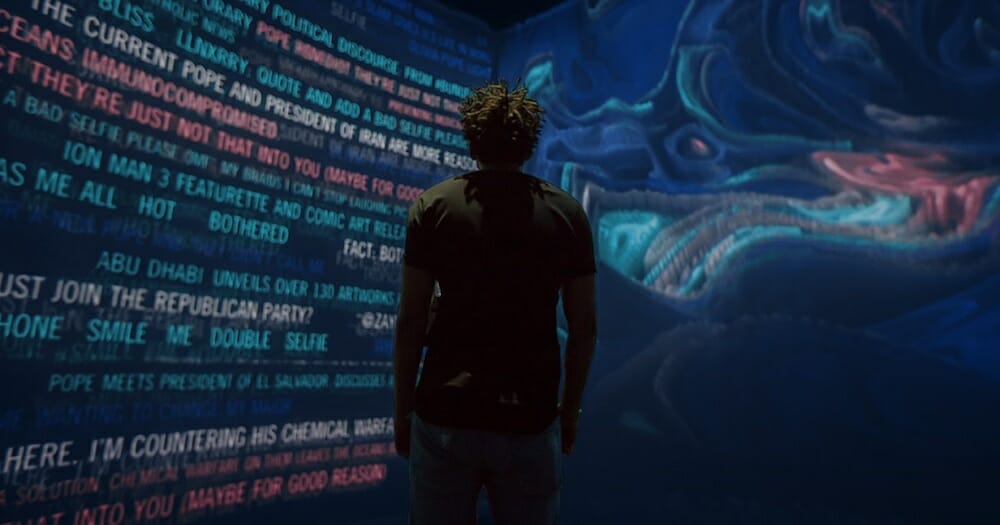

The language of playbacks, hills and sponsor users has spread across the company, too. Our immersive bootcamps successfully brought Enterprise Design Thinking to hundreds of teams. Many of the people who came through our bootcamps have moved on to new projects, spreading their practices as they go, far beyond our program’s direct reach. The bootcamps have now largely been replaced by a digital platform that has the capacity to bring Enterprise Design Thinking to an even larger audience. It has already reached hundreds of thousands of IBMers as well as thousands of college students and IBM clients.

As another sign of the evolution of our program, we recently released one of the most comprehensive design systems in the world. The IBM Design Language articulates a philosophy and a set of elements that designers can use in any number of disciplines such as brand, software product design, and digital content. The goal is to make it easy for designers working within and across these disciplines to achieve “unity, not uniformity”, in the words of Eliot Noyes who did extraordinary design work for IBM in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Progress & Impact

We have been very fortunate that our CEO Ginni Rometty gave her full support to our team, seeing our work as contributing to her ongoing transformation of the company. It was also a good move to focus on a well-defined capability gap – design skills – giving us both a long-term objective and a model for incremental progress.

Even as we engaged initially on a small scale, Phil always challenged us to think in terms of how we would scale up. Initially I found that hard. I was often tempted to tailor solutions to the specific situations we encountered. To be able to scale, you have to do the opposite. You have standardize how you execute so that what you do is repeatable and can be delivered on a large scale by a few dedicated people. This is a key element of a program focused on the whole company, rather than, say, a shared service for design or an innovation lab.

Agility was another essential ingredient. For the first few years we saw ourselves as a startup inside IBM, and we strove for the same agility that a startup thrives on. Beyond the real-time hands-on engagement and trouble-shooting that implies, we were willing to reorganize ourselves at least once a year, sometimes quite radically.

When we started, we said we’d know we were done if we could walk away and it would run itself. We used to call ourselves IBM Design, but we decided recently that name should be the moniker for all aspects of design across the whole company. We now call our team the Design Program Office, and it’s smaller than it was at the peak of our efforts to change the company. Wherever possible, the program office takes a back seat to the business units. Of course, nothing is perfect and it still feels too early to declare victory. We’re on a journey of continuous learning and improvement, and we will continue to make adjustments and look for further innovations in the future. What’s exciting is that we no longer have to do that ourselves. The seeds of further innovation are now firmly planted in our business, at the team level, and increasingly in our leadership culture.

This distributed design capability is reflected in the business outcomes we are seeing. Teams across the company are now able to bring new and improved products to market much faster than they could previously, a critical success factor in a rapidly changing market. IBM is also now widely recognized as a leader in design and design thinking at scale, and IBM Services teams are using this expertise to help clients address challenges and opportunities in their own businesses. Perhaps most importantly, our leadership culture has shifted enough that design is now considered an essential ingredient of any new initiative, and senior leaders now pay as close attention to measures of user success as they do to financial and market metrics.

My own job has changed numerous times over the past few years, from helping to develop our design thinking framework, to coaching teams, to helping define our technical career path for designers, to bringing new tools to our teams. Along the way I kept my hand in a couple of strategic design projects. Today, I still report to Phil but I’m on loan to the business nearly full-time these days. This is, to be honest, a relief. When I first went to work with Phil, my previous manager sent me an email reading “Congratulations – you’re now overhead!” I’m a product designer at heart, and I’m back working to translate our strategy into compelling products and experiences. But as I work with my new team on these projects, I know that a new platform is up and running and at our disposal. It’s a platform of design, designers, and of design thinking culture; a platform that helps us all focus on solving our users’ problems better than ever before.