Designed for Harm

How Products of Policing Enforce Extra-judicial Practices of Control and Submission

The conversation about policing is a Molotov cocktail of trauma, bias, propaganda, and cognitive dissonance. Many Americans are raised to think of the police, and by extension policing, as a mechanism to protect and serve. Yet, this stands in stark contrast to the experiences of those who interact with one of the nation’s largest and most dominant civil services as a purveyor of fear and dominance.

Illustration by Sophia Richardson

By Timothy Bardlavens and Jennifer Rittner

While the binary of “good cop vs. bad cop” lays blame at the feet of the individual, that framing is ultimately inadequate to interrogate the fundamental challenges of policing practices, in particular the physical and psychological damage wrought by products of policing.

Safety & Mediation or Control & Submission?

If we remove the rose-colored definitions and media-fueled propaganda around policing, ultimately there are only two definitions that matter: control and submission. Policing is, at its core, control; and that control is often applied through acts of forced submission. The brand language of policing—protect, serve, safety— justifies all manner of abuses under the guise of law and order, which viewed historically, reveals a system built by people in power to control a broader group, with the explicit goal of having them operate in ways that they—the powerful—deem acceptable and moral. We certainly agree that the prevention of loss, death, and destruction is paramount to a healthy, thriving society. In this instance control = good. But control is not evenly distributed. In fact, it is disproportionately levied against historically underrepresented communities, among them Black, immigrant, poor, neurodivergent, disabled, gender non-conforming, sexual minorities, and religious minorities.

The uneven application of law and order never rang more true than on January 6, 2021 when insurrectionists stormed our nation’s Capitol, an event that was planned on social media under the watchful eye of law enforcement, who responded with what can best be described as an inept show of force that ultimately led to death and destruction of individuals, physical property, and the national psyche. The discreet absence of law enforcement on that day stands in stark contrast to the Black Lives Matter protests on June 2, 2020. Protest participants reported what was captured in photos from that day: a dramatic show of force from the National Guard who lined the stairs of the Capitol building in pristine formation, armored and ready for war. If policing is control and submission, these events are their products.

Products of policing reflect the history of torture that backed the currency of our nation’s founding, hailing back to 400 years of con-trolling Black bodies. This unholy history forms a thick layer of socio-psychological dust covering every surface of that one room in a home that no one wants to enter, for fear of having to identify, mourn, and accept the past that is so deeply connected to and influential in our lives.

This is the level of control the mere presence of a patrol car has on Black bodies, this visceral feeling of fear.

An Unholy History: Patrolling as Situational Profiling

Some of the first policing systems in the American South began as a means for controlling its Black population in the form of slave patrols. Created in 1704 within the Carolina colony, slave patrols’ sole duty, unlike constables and sheriffs, was to enforce colonial and state law. White citizens took an oath to “faithfully discharge the trust reposed in them as the law directs,” and traveled from farm to farm in order to observe slave activity, provide security, and punish slaves who violated plantation rules.

Slave patrols weren’t merely reactive, activating only when an enslaved captive ran away. They were a proactive means of control. Their mere presence, in uniform, with badges prominently placed, was meant to be a deterrent—a warning to the captives not to even fathom claiming the right to bodily autonomy or justice. This consistent patrolling of plantations and the Black bodies that resided on them, or stopping and questioning Black people who seemed “out of place,” was a system of mass control that mirrors the over-policing of poor, majority-Black communities, and serves as the inception of predictive policing in America.

In fact, majority Black communities experience this practice of patrolling every day, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. High-touch police presence in marginalized communities contributes to the feeling of being criminalized and ensures that minor crimes, crimes of poverty, and pre-crimes (See: broken windows policing) are caught and over-punished, validating higher police presence, which ensures a greater amount of arrests, thus driving up the crime rate, justifying a heavier police presence. Of course, the practice isn’t special to com-munities with heavy Black populations. The surveillance of Black bodies, under the sup-position of illicit activity, extends to any space where the individual is “out of place”— whether jogging in a middle-class neighbor-hood, driving a luxury car, napping in a college lounge, walking home from the store with chips and soda, or simply existing with the condition of having black and brown skin. Police call this situational profiling, or the act of assessing perceived illicit activity based on context surrounding a potential suspect. Meaning, police are able to more effectively impose control over an area, feeling justified in randomly stopping individuals for ambiguous laws or simply because they “look suspicious.”

Scenario A: Driving While Black

Two residents are driving through a middle-class neighborhood, one a white woman, the other a Black woman. Both are driving the exact same car, going the exact same speed. They pass a police officer stopped at a stop sign, the officer turns onto the street behind each individual. What is each person doing?

• White driver: Hasn’t noticed the officer, continues, largely unbothered, OR, Notices the officer, checks speed, continues, largely unbothered.

• Black driver: Notices the officer, checks her speed multiple times, slows down, touches her seat belt, thinks back to ensure she didn’t run a sign or light, repetitively checks her rearview mirror. She thinks about where her driver’s license and registration card might be, and worries that her movements will be misinterpreted if she reaches for them. If she has preplanned, her documents are strategically placed in her car so that she can optimize her movements to access them without incidentally provoking the fear response of an approaching officer. She lowers the music to make sure the interior space of the car is calm and still. She neutralizes her affect, practicing her verbal response in her head. She feels both scared and angry. Her heart rate elevates and her concentration becomes hyper-focused. She enters a post-traumatic state that continues whether or not she has been stopped.

This is the level of control the mere presence of a patrol car has on Black bodies, this visceral feeling of fear, of hoping the officer will turn on the next street, or that their lights never flash on. Not because of any guilt of illicit activity, but because the history of control and submission has been ingrained.

Scenario B: Drugging While White

Two college students are walking in their college town with a small bag of weed in their pockets. Both young men are dressed casually, carrying a backpack, and texting as they walk. They see a stop-and-frisk station up ahead. What does each one do? We offer this exercise for your consideration. How do you imagine a Black student and a white student responding in this scenario? In our own personal experiences, we have witnessed Black friends, neighbors, and even family face arrest for low-level drug possession, while white friends, colleagues, and classmates routinely purchased, sold, and used drugs with impunity. That reality was starker prior to the legalization of marijuana in parts of the country, but it continues to inform the difference between how Black and white youth interact with police around assumptions of criminality.

The patrolling, surveillance, and situational profiling of Black bodies was the job of slave patrols and is ingrained into the role of police. Their presence, the markings on their cars, and flash of their badges are all meant to be symbols of authority, not safety. By definition, authority assumes the right to enforce obedience.

Products of Control

An audit of the products of control includes both objects and actions:

Patrolling

The act of claiming ownership over the movements of others alongside the threat of punishment for those who are deemed out of place or out of line. Patrolling establishes a hierarchy around who has access to free movement and who is subjected to constraints. (See: Slave patrols)

Surveillance

The surreptitious tracking of individuals with-out their knowledge or consent, which is often based on preconceived notions of where criminality happens, what it looks like, and who the perpetrators will be. Surveillance often catches, and therefore punishes, the surveilled, reinforcing the idea of criminality as predetermined. What it fails to capture is analogous criminality (or behaviors deemed criminal) in places and by people who are not under surveillance. (See: Predictive Policing)

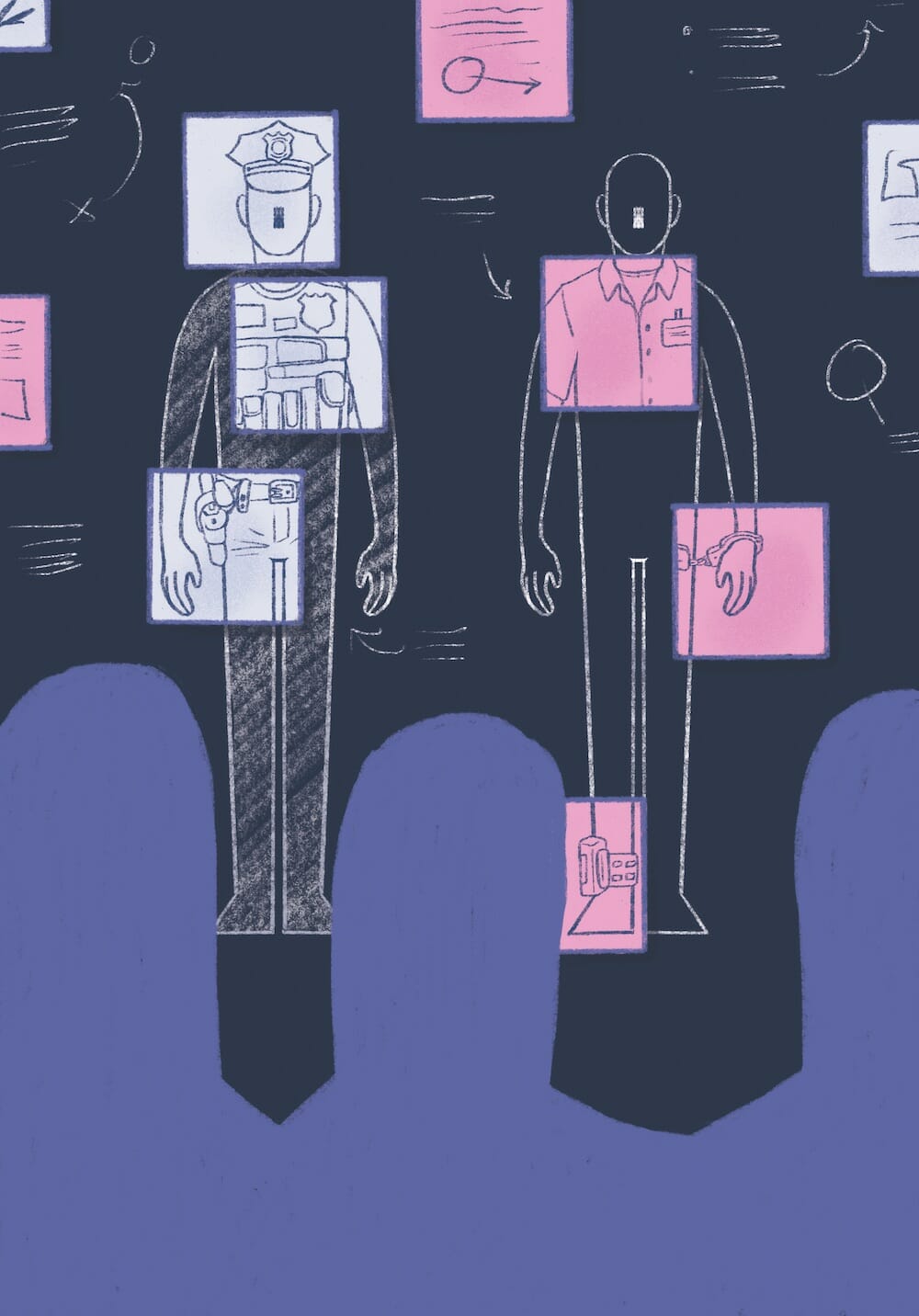

Uniforms and Vehicles

Depending on one’s place in the social hierarchy, the uniform and badge are worn either by those who serve you or oppress you. The police cruiser is either an indication of safety or an impending catastrophe. Lights and sirens either mean that help is on the way or the reminder of trauma. (See: January 6, 2021)

Zoning

The state’s determination concerning what types of activities can occur in a particular place, which can be weaponized to punish those who are deemed to be acting in a manner inappropriate to the established zone. Perceptions about who belongs in spaces and how people behave or comply with the rules have been ingrained to the degree that citizens have assumed the right to police other citizens, as if re-enacting the slave patrols of their ancestors. (See: Barbecue Becky)

Weapons

Symbols of strength and dominance, guns, tasers, tear gas, and flashbangs are the tools of terror used by police to justify force. Just as the slave patrollers of the 19th century brandished weapons to exert their will over Black bodies, police today draw their weapons as a matter of routine. We’ve seen guns drawn as an immediate reaction and a mechanism to circumvent civil conversation and de-escalation, moving directly to extra-judicial compliance. One of many examples is representative in the video of Sandra Bland being arrested on July 10, 2015, where she exerted her right to smoke a cigarette inside of her car during a police stop along the highway. Her act of personal agency triggered the officer’s assumption as sole authority, and as she failed to acquiesce, his response was to draw his gun and force Ms. Bland out of her car. The message is simple, “Submit or suffer the consequences.” The inclination to reach directly for a gun, especially with Black bodies, is inherently founded in the toxic stew of fear, supremacy, and dominance. (See: Sandra Bland)

Products of Submission

A similar audit of the products of submission reveals the psychological domination inherent to the practices of policing.

Intimidation

The act of using physical and psychological force to impose dominance over others. Intimidation is a key tactic in maintaining unquestionable authority and is a commonly accepted practice in maintaining control. From the show of force against Black Lives Matter protesters, to the language of brutality used against suspects at the site of an incident or in interrogation rooms, to the wielding of weapons against unarmed citizens, intimidation has become equated with power and authority. In fact, they are weapons of fear of impotence. Just as riots are the “voice of the unheard,” intimidation tactics are the tools of the weak-spirited who assume unearned authority over those who are in no position to fight back. (See: Weapons of policing)

Non-Autonomy

Forcing the accused to submit their own body to self-incrimination, the police line-up predicates purported success on the notion that a traumatized victim could adequately distinguish from among a handful of individuals who are, by virtue of their presence in the line-up, probable criminals. The line-up is designed and intended to make each individual body seem guilty. Vulnerable in their appearance of guilt, subjected to the vagaries of perception, this product of policing serves to dehumanize subjects as essentially unindividuated. False-positive identifications con-firm the ineffectiveness of the line-up, and historically, the form references the slave auction, in which bodies were lined up by slavers to be observed and judged by those who had the privilege of standing on the other side of the color line. (See: Shaka King)

Restraint

No encounter with the police would be complete without the threat of being physically restrained with handcuffs. The threat alone is an act of terror that often causes suspects to react in trauma as they hope and try to avoid being forced into physical submission. Anyone who has not experienced forced restraints should interrogate what it feels like to be stripped of one’s bodily autonomy, extra-judicially, because a person with a badge has the authority to do so. Now imagine your body lying prone on the ground—on a public sidewalk—completely vulnerable, while a full-sized human kneels on you and demands that you offer your body up to those restraints. The handcuff is more than an object, it is an action that dehumanizes the individual who the police officer deems a threat, but who has, more often than not, not been convicted of a crime. Handcuffs say, “You are no longer a free person. Your body is not your own.” (See: Honestie Hodges)

Humiliation

Forcing accused suspects to endure a performance of guilt, police departments coordinate with local news reporters to publicly humiliate suspects as they make the walk to or from police stations or courthouses, effectively adding to the trauma of having been accused of a crime. It’s important to note the historic, racialized pattern of news coverage. (See: The Central Park Five)

Torture 2.0

On February 1, 2021 a 9-year-old Black girl in Rochester, NY ran out of her home during a family argument and, eager to get her back safely, her mother called the local police for help. Cop-cam video shows the child being sur-rounded by a group of men—strangers to her—forcibly grabbed and dragged by at least one, and at one point wrestled onto the ground—in the snow—by two of these men who tower over and yell at her. Her voice shrieks in fear as she begs for her father, trying to release herself from their grip, as they handcuff and force her into the back of a squad car. As she continues to react out of fear and confusion, they perceive her reaction as an unwillingness to submit, and pepper sprayed this 9-year-old child. Out of perhaps an ironic twist of self-awareness, one officer reproaches the young girl for, “acting like a child.”

Submitting to the police is an unevenly spread expectation across the faces of the American people. Many of the same individuals who believe the police exist to protect and serve, also believe they have the right to push back and challenge the police with righteous indignation. Contrarily, those who see the police as agitators and fearmongers are expected to capitulate

to the police’s every whim, to prostrate themselves to authority.

This culture of submission insidiously manifests in our cultural norms, which attach inherent meanings to a person’s public guilt. Intimidating, restraining, and humiliating bodies are the products of submission so deeply embedded in policing.

The practice of public humiliation, while being restrained, by authorities can be traced to the use of mechanisms like the pillory, a wooden device used in the 17th century that forced a person to bend over, stick their head and hands into holes and then be locked in place. These people would be put on display in public, to be ridiculed, condemned, and even abused by the citizenry. That said, the practice of dehumanization and humiliation lands more squarely on the doorsteps of the U.S. with the introduction of “buck breaking.” The act of restraining male slaves to posts or with horse hobbles, then raping them in front of their families and other slaves or forcing two slave men to have sex with one another.

While this obviously isn’t a common practice today, the tendrils still exist through the co-dependent relationship between the police and the media. Perp walks are a product of this relationship, which results in the putting of bodies on display to warn communities of their place, the swaying of public opinion of an individual’s guilt or lack of humanity, the hero worshiping of police who “got their man,” and the demasculinization of Black men through threats of rape and sexual violence while in the hands of government-run systems of incarcerative oppression.

Designing Against Harm

Policing was uniquely designed for the psychological and physical control and submission of a populace. Over the past several centuries products have been refined and redesigned for efficiency and effectiveness, but the system and its goal have remained the same—protect property and power. So when do we begin addressing the system AND products?

In product design, one of the most com-mon whiteboarding exercises is a prompt to reinvent the ATM. Generally, whiteboard exercises are meant to gauge an individual’s product thinking, to see how they think about the needs of people, and how they vocalize their process. This prompt in particular is unique because the best response is always, “Why do we need ATMs?” As designers, we often iterate on preexisting products, instead of deeply assessing and questioning why they exist. This is the fallacy of policing, and by extension, its products. Policing products have been designed and redesigned for centuries, resulting in “innovations” like tasers, flex-cuffs, flash-bangs, predictive algorithms, and increasingly opaque surveillance mechanisms.

These innovations fail because they focus on the product at the expense of meaningful systemic change.

• Innovation Failure Horse hobbles redesigned as shackles, redesigned as handcuffs, redesigned as zip tie cuffs.

• System Interrogation What is the purpose of restraining people? How can we keep an individual from hurting themselves or others while in police custody? Would handcuffs or other restraints still be the answer, or is that the easiest option because it exists?

Dismantling the police isn’t a call to destroy the police, but to abolish the system, practices, and products born out of the torture, dehumanization, and destruction of human bodies for the explicit and implicit goal of preserving economic and state regimes. Reimagining, and by extension redesigning, policing and its products is the process by which we create new means of equitably protecting the citizenry, ensuring every per-son is treated with dignity, while prioritizing the preservation of human life above all else.

Systems, practices, and products are designed, and can be redesigned—IF we can acknowledge and accept the foundation was never broken, but has always worked by design.