Design Activism

A Dialogue on Protest, Policing, and Demanding the Future We Need

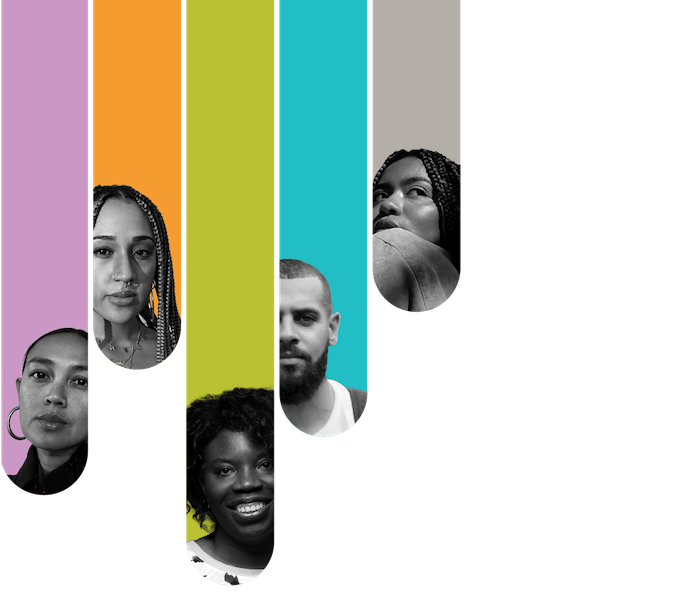

On February 9, 2021, Niki Franco moderated a conversation with Ivy Climacosa, Dustin Gibson, Annika Hansteen-Izora, and Liz Ogbu around the new protest movements that have arisen in reaction to the ongoing scourge of police brutality in the United States. As designers and activists, the participants were invited to talk about their own creative practices, including, according to Franco, “The relationship between artists, designers, and folks on the ground.” Together, the group addressed the various crises people of color experience in this country, including, “the spatial dynamics that contribute to racism, classism, anti-homelessness, ableism,” and more.

The following is a transcript of their conversation, edited and condensed for clarity and space.

Niki Franco (Miami, FL), Moderator: I’m so grateful to be in conversation with each of y’all. I’m a true believer, in Gemini fashion, that we are most apt to tell our own stories, so I would love to hear a little bit about who you are and what brings you to this space.

Annika Hansteen-Izora (Brooklyn, NY): I use all pronouns. I’m a designer, art director, and a writer. One of my day jobs is as Creative Director of Design and UI at Somewhere Good, which is a soon-to-be-released social platform designed to help people of color connect around the things we love.

Liz Ogbu (Oakland, CA): She/her. I’m trained as an architect. I probably still do that in some form, shape, or fashion. I describe myself as a designer, urbanist, and spatial justice advocate; and I run a consultancy called Studio O, working at the intersection of racial and social justice, because I think as long as we are separated and selectively harmed by space, we can’t actually achieve racial justice. I work in mostly low-income communities of color all over the world, but specifically here in the U.S., looking for ways to use design to push for justice.

Dustin Gibson (Atlanta, GA): “Who are you?” questions always feel super heavy. I feel like I should start with at least my great-grandmother, [whose] organizing informed the work I do. I’m an abolitionist and that guides the work I do building peer support models for people that are getting out of the asylums and nursing facilities and prisons and jails; and all of the organizing that takes place in between to make that happen.

Ivy Climacosa (Oakland, CA): She pronouns. I’m a worker-owner at Design Action Collective. I’ve been there for a little over 10 years; and prior to that I’ve been organizing in the Filipino community, building grassroots organizations in my community for 15 years or more. So I’ve been in this intersection of organizing and design for a bit and wanting to amplify our spaces to be as equally rich and engaging, and trying to be a resource for folks on the ground to meet the goals of our community.

Intersections of Art and Activism

Niki: I want to start this conversation by grounding us in the non-negotiable relationship between creative producers (artists, cultural workers, designers) and activists (folks on the front lines of social justice, including organizers and even folks that are incarcerated). We know that these two have always existed in tandem and supported one another. During the summer of 2020, in a time when we were not able to share space as easily as we would like, and were looking to our phones, looking to information systems to learn, “What are folks doing? Where am I needed? How do I connect? Where are mutual aid projects?” I think that dynamic was really uplifted.

In the tradition of Toni Cade Bambara, the role of the artist or cultural worker is to make the revolution irresistible. How are you swimming in that water, trying to be in deeper relationships with folks on the front line and bringing your talents of design and artistry to contribute into this new world?

Ivy: At Design Action Collective, we are in network or in community with other formations like Grassroots Global Justice Alliance and the U. S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives. Locally, we co-founded a space called Third World Resistance, that includes, “people of color community organizations” that are anti-imperialist, that are movement building. We have been a resource ally with the organization to be the cultural arm that creates visuals for campaigns the network wants to move forward or highlight.

Being in constant community with folks has helped us to see what is really resonant, what needs to be amplified. We’re creating spaces and sharing information, doing workshops, political education with organizers, and asking, “What is effective design? What are the tactics of visual narrative that can really propel our story?” We maximize all this effort when people put their bodies on the line and take space.

Annika: I also think of being in community with folks. That was very much how I was thinking about the current movements, because when the uprisings occurred, I think it really had folks reckon with the thought that everybody has a way that they can be participating in movement work in their own spaces. At the time I was the Creative Director for Ethel’s Club, which is a social and wellness club for people of color. In that moment we were thinking about, “How can we provide space for people of color to rest, to heal, to engage in pleasure, to be with people that already see them, and not having to be under the white gaze. How can we provide free healing sessions between Black folks and trained therapists and healers?”

As an artist working with design in digital mediums, I was asking, “How can I create resources as someone whose movement work is really rooted in writing, in communal care, in poetry?” I created resources for folks to connect to one another and share resources, to be seen through the power of social media, and actually being able to reach others, to do something. Creating resources is really important and learning is very important, but how can you align that knowledge with action? And what are you doing with that knowledge beyond just seeing an Instagram post giving you information? What are you actually going to do with that? So I focused my work on connecting people to one another.

Liz: What Ivy and Annika said has really spoken to where I feel like I’m operating. I do think that the work that I do often is pushing the envelope, but when we’re talking about what “the revolution” is, There’s a tendency to think that the only useful roles are those who are out on the street, actively fighting in the resistance. If we think about it as an entire ecosystem, we need folks who are doing that and we need the folks who are dreaming for what can happen, and we need the folks who are hanging back a little bit to try and bring the laggards who are slowly waking up. It’s important to figure out what your role or roles are going to be.

I feel like mine somehow operates a little bit in the dreaming of what’s happening next, dreaming of the future. So in some ways the events in the spring and summer were basically like, “All right, I gotta dig deep and start plotting.” When this comes down, we’re going to need something to go to next. We can’t just go to nothing. So that has meant really deepening the anti-racist work that I was doing with communities and envisioning what anti-racist communities look like, I took advantage of speaking gigs to openly say to the design community, in particular, “You can be an actor and be complicit with all of the harm that is horrifying you right now. Or you can be an ally and step up.” Or actually, where I really want to land is, “Become an accomplice and risk something, because there are folks who are dying. There are folks who are suffering and we’re all here comfortable with our signs and our hashtags, but not actually doing anything.” So, a lot of my talks started to get a little bit more aggressive like, “We don’t actually have time to be with the niceties right now.” Like, “shit’s happening, people are dying. Step up.” Trying to shift institutions to actually, literally put their money where their mouth is and change our practices has been calling to me in this time.

Dustin: As you were speaking to Liz, I was thinking about Amiri Baraka, who said we need poems that shoot back and we need poems that kill. A lot of my work is concerned with expanding our understanding of ableism and how the disabled body and mind is central to undoing anti-Blackness and all the other systems that are interconnected with it. And one of the things that we’ve discovered is Black folks in particular have talked about disability in very nuanced and complex ways, but we haven’t necessarily used the Western language to do so. So it typically comes out as, “Hey, Black people need to talk about mental health.” When in reality, if we hadn’t talked about mental health we wouldn’t survive and we wouldn’t be here today. So we utilize the songs of Nina Simone, we utilize Blind Willie Johnson’s records and Meek Mill and J. Cole, and talk about the ways in which we have nuanced and complex understandings of what’s happening to us.

The role of the artist is not necessarily just concerned with the product. The process in and of itself is a journey and a thing that we pay attention to in disability communities. We’re thinking about access to creative practice. Ruth Wilson Gilmore talks about abolition changing the way we interact with each other and the planet. I view access and interdependence as central to the practice of changing the way we relate to each other. Through that, we build some of the communities that Annika lifts up and Ivy lifts up. Some people have done that beautifully, like Leroy Moore (of KripHop Nation) who uses his voice, the disabled voice, as well as writing to not only excavate the history of where we’ve been, but to put forth a way of entering into this creation, this practice in a way that is more accessible to folks. And it’s access-centered, meaning that we’re building relationships while doing it.

Niki: Yes, yes. I have deep resonance right now. I feel it in my body.

Liz, thank you for also challenging the binary in which the question was posed. I think of Deepa Iyer from the Building Movement Project who mapped out this beautiful ecosystem of all the roles that go into it social change: guides, storytellers, healers, disruptors, caregivers, builders, visionaries, frontline responders, experimenters, and weavers. We’re so deeply interconnected, but there’s this idea that there’s really only maybe two to four roles that folks can fit themselves in. But that’s not real.

Y’all brought up so many revolutionaries that exist in our legacies who’ve been embodying this. We know that in order to get to the next stage of where we want our communities to be and how we want them to feel, we need to dream, but we also need to be rooted. We have to have our feet on the ground and our head in the sky, dreaming for something more. We know that we’re not the first ones to think this. Abolition is nothing new; it runs deep in our legacy.

Healing the Crisis of Imagination

We know that the carceral state, and all oppressive systems, largely depend on a crisis of imagination. 2020 created ruptures in that lack of imagination in many ways, as folks were asking, “If not this, then what?” So many people were offering visions that actually felt healing, felt rooted in care. When we’re trying to reorient ourselves around the question of, “What can communities that are safe and supportive look like?” I think of all the roles that we just talked about. All of the ecosystems coming together and aligning to move forward.

How are you untangling the crisis of imagination in your work?

Ivy: People tend to go back to the same symbolism over and over again, so we’ve been creating our own visual narratives. At the beginning of the pandemic we created a graphic called Solidarity is Safety, defining what safety looks like in our communities, including mutual aid or being able to care for each other. Modeling what it means to dream from a place of abundance and not scarcity, challenges the notion of, “Oh no, we can only dream so little.”

Liz: Ivy, what you said really spoke to me, and I literally had just written down, “We’ve never seen what it is that we’re heading to, or that we’re dreaming of, but we know what it feels like.” So I think it’s like, how do we get deep into our bodies, and understand that we know the truth, even if we’ve never actually experienced it before, and use that as a little bit of our North Star? For me, it’s leaning into that feeling and not being afraid of it and understanding that, because we have all been nurtured in systems of oppression, that comes second nature to us. The de-programming isn’t just about our institutions and our spaces and our art making. The de-programming is also within us.

Part of the system of oppression is that you don’t get to dream. You just exist in these two states: either you’re being urgent, which is more about an emergency than a critical need to solve; or it’s about forgetting, like getting to a place where you can forget again and be complacent. So, some of the dreaming is asking, “What’s the third way?” We shouldn’t just be aspiring for doing good or good enough. We should be aspiring for what it would be if we were all free. The question in pretty much all of my project teams is, “What does freedom look like here and how are we participating and keeping that freedom from being achieved?”

In a project that I’ve been working on in Charlottesville for five years, we had been talking about what an anti-racist model of housing would look like. That was well before this year, but it took on a whole new urgency, as the conversation focused on discovering what self-determination for those residents should be, and how we become participants in making sure that they get it. That’s what’s driving us.

The goal has to be their self-determination, not a new housing development. Every action we do emanates from that. I can’t say I know what self-determination for those residents looks like, but I know what it feels like. And I know that we’re on this journey to create that liberation. It requires an ability to take risks, which is one of the things that we don’t necessarily talk about as much, that safety is about trust and trust enough to be able to take a risk, whether it’s a risk of a feeling, a risk of an action. How do we build relationships of trust within all of the spaces that we’re making and shaping?

Dustin. Liz, as you’re talking about abundance, I have to mention Elandria Williams, who became an ancestor last year. They wrote a poem called, We Are Worthy, which is about a striving for abundant communities. They were also part of this group that made an anti-capitalist curriculum that included a section called Beautiful Solutions with a hundred examples of solidarity economies across the globe, like Alaska Permanent Fund, or examples of people buying trailer parks or different co-ops that have been organized. And that’s a really useful tool to, 1) know these things are possible and they exist, and 2) think about the amount of accommodations that have taken place and transpired during the pandemic. These are things and demands that disabled people have been making for decades. Some people died behind it. People have struggled for it. And because we’re in this moment where we’re trying to figure out how to continue the level of production for capitalist systems, we will begin to accommodate people for that.

So I raised that poem as a way of restructuring how we believe we’re valued in society, right? Capitalism intrinsically ties our value to what we can produce for a master, essentially. But for us, it has to be different. The group, Us Protecting Us that I’m part of in Atlanta, is where disabled and non-disabled people are coming together to organize around, “How do we respond to the crisis in our community?” Just on Saturday we had more people join. And one of the things that somebody mentioned was, “Hey, I had a positive experience with the officer. They came up to me when I was in crisis and they didn’t pull a gun.” Like, that’s a very real value set that we have. I mean, we’ve been socialized this way, right? Programmed. But that’s something that we as organizers or folks that are concerned with this have to figure out ways to respond to. And I think that’s the heart of the question, the lack of imagination.

I’m really inspired by folks that, in a very visible way, have been stripped of not only resources, but also all of the reasons to imagine and still create things. Like, I’m thinking about Todd who was a prisoner in Pennsylvania who paints on leaves. And he paints on leaves because that’s one of the materials or mediums that he has access to, but his paintings didn’t tell the story of the seasons, the places in Pennsylvania that he’s gone to. [His paintings] talk about the separation of family and moving all across the state for different political reasons and whatnot. But those types of things, like, the idea that we could actually build with what we have is really important to how we imagine things. I at least have experienced a lot of meetings where we start off by saying, “What do we need? Who else do we need in the room? Where can we go and get XYZ?” But it feels like we have a lot of tools at our disposal already and we can build from where we are.

Annika: I really appreciate, Liz ,what you were saying about calling in a world that we can’t see, because I feel like a part of untangling the crisis of imagination is actually insisting on the potential for new futures. I’m here because I’m the beneficiary of the imagination of Black, trans, queer, and disabled elders. And I think about how they were dreaming of and fighting for a world that they knew that they wouldn’t even see, necessarily, that they might not see the outcome of.

In my own art, I’m creating for a world that I will not see, and yet I still believe in the potential of that world to be pulled into the present. Saidiya Hartman said, “So much of the work of oppression is policing the imagination.” In design, white supremacy ends up manifesting in the discourses and texts and institutions that are heralded as, “This is what design is,” that are often assuming who the audience is: not only white, but white and well off, and white and heterosexual and cis-gendered and able-bodied.

We see the results of that in imagination. Untangling that starts with challenging assumptions in pretty much everything I can think of, especially, in creating systems of care and thinking about how we can be supporting each other in this work.

Designing the Demands and Politics of Space

Niki: I want to talk a little bit about space. As designers, organizers, urbanists, y’all are constantly thinking about space. In my own reflections from 2020, I began thinking a lot about spatial politics, considering questions like, who’s on the street? Who has to sleep in the rain? I began thinking about the power of thousands of young people of color blocking a key highway in Miami, Florida, and incarcerated folks organizing from the inside to be in solidarity with the folks that were outside of that building; making noise with pots and pans or whatever they were able to get to and letting folks know, “We are here and thank you for seeing us.”

How are you negotiating spatial politics in your work, including negotiating questions of access, and challenging norms that are inherently classist, ableist, and anti-Black?

Dustin: There’s an article that Robert “Saleem” Holbrook wrote while he was in solitary confinement called, “Control Units: High Tech Brutality,” and in it he referenced Dr. Mutulu Shakur, who talks about solitary being designed as a device of deprivation. The work of freedom is attempting to destroy all notions of us not being interdependent with each other, right? Not this idea of American exceptionalism where we can be independent, but us being able to be together. However that is, even on Zoom. . . and this is important . . . Zoom has been shutting down pro-BDS and pro-Palestinian gatherings online. So even in this place, we’re policed.

Thinking about all the ways we can be together is important to me. Judith Butler writes a bit about modes of participation—the right to assemble and to gather that is essential to being a part of any type of democracy. A lot of disabled folks can’t gather in spaces because they’re inaccessible. Trans folks can’t gather in public because it is something that society is not okay with. Women are not able to walk down the streets safely. So there’s a bunch of reasons why we can’t assemble. The protection and the struggle to be able to do that feels very central to our politics, because in order to progress, we have to be able to deliberate and come together and talk; and not just talk, but communicate in all of the ways.

Liz: What you said about interdependence is really interesting, because I think that the spaces that we’re in for the most part are defined by the normalcy of whiteness, right? That undergirds the terms and conditions of what we consider good space versus what is bad space. And how I was trained—architecture education—is intimately steeped in white supremacy. So I was trained to be a great white supremacist. It’s an active act to break away from that and question it; and part of the questioning and part of that road means that I have to look at who’s not included, whose stories are being left out, who was I taught not to see, and understanding that my ability to exist in this place has to be deeply interwoven to those who the system has said are invisible.

That means that I always have to see them. I always have to bring them to the table. I always have to try to see the world through their eyes because it’s the exact opposite of what I was taught. You know, I grew up in Oakland. I live in Oakland. I’ve seen it go through a lot of changes. Increasingly, who is perceived to be invisible by the systems, determining the space, it just hurts, right? Like the encampments that you see underneath the freeway, even in the time of COVID with all the restaurants, and the outdoor dining, and stuff like that. I’m just sort of like, there are so many people who are not seen by this, whether it’s the homeless person who you’ve cleared out so there can be free walking space for the people who are coming to patronize the restaurants or the disabled person who literally cannot see the crosswalk. I can barely see the crosswalk in between all of these things that have been set up so that people who want to eat outside in the time of COVID can do so.

It’s not a new thing that we have existed in a world that is about not seeing other people’s humanity as the normal part of existing. But I think right now it feels even harder because not seeing humanity is literally leading to massive death. The key to re-scrambling our relationship with space is getting to the place where we understand what it means to see the people that we have ignored or rendered invisible before.

Annika: When I think about urban space . . . I’m from East Palo Alto, California and Portland, Oregon. Portland is already so white that people wouldn’t think that it could be gentrified, and yet, it has one of the worst gentrification rates because of how violently it came through the Black community of Portland, and completely uprooted that community, and instantiated its idea of what a neat and orderly and nice design space can look like. Rapidly gentrified urban centers have a design look. We know what that look is. There is the gentrifier font, which is like, if you see a sans-serif sign go up in a neighborhood, then you know that it is about to uproot an entire community that has been there before. The “universal” type of design in these neighborhoods, in an attempt to make them nicer, ends up recreating systems of domination.

Ivy: As an immigrant, I think it’s been this lifelong struggle to be like, “How can we take space in the communities that we inhabit.” I used to work in the South of Market area in San Francisco, this mecca of technology, right? It’s such hot real estate for people to take over neighborhoods. It also happens to be one of the highest concentrations of Filipino immigrants who had come with families and shacked up in small apartments together for years. Some of my friends applied for it to be a heritage neighborhood. They were able to advocate for the Filipino community to have a space, to say that we’ve been here for a long time, we’ve contributed to making this community vibrant. Our neighborhoods, our cities are supposed to reflect the people that have built it up. So how do we take up space? I think a lot of it is also how do we heal our communities to feel like it’s okay to advocate for these things.

Dustin: There’s this level of absurdity around the murders of Natasha McKenna and Janice Dotson-Stephens—people who were existing in public in a way that was deemed inappropriate. We have a long lineage of that, right? I mean this colonial project of the U.S.; we have ugly laws and public charges and Black codes and all of these ways in which we’re not only policing “who” but “how people can behave.”

The power in what happened in St. Louis in 2014, when people were saying, “Who’s streets?” That brought so many people into the movement? I think a part of that was, whether it’s subconsciously or consciously, understanding that they’re doing that shit in our name, right? That jail? They built that in our name. That prison? They built that in our name. Right? These are all supposedly public institutions. And that is ours. The streets are ours—thinking about colonized peoples, specifically. The design of that is hidden in plain sight. So the jails damn near every downtown, any county jail, you don’t even notice a jail unless you’re from there. In Pittsburgh, the kid jail is hidden by trees so you can’t see it even though you’re 200 yards away. That’s designed purposely. The prisons or institutions are typically geographically dislocated from communities.

The deinstitutionalization movement [of the 1960s] sent hundreds of thousands of people out of asylums, state schools, and hospitals, into different forms of institutions. Group homes and halfway houses look like houses or apartment buildings, but if you go in there are padlocks everywhere, plexiglass, very little furniture, 24/7 surveillance. The question is, “Are they free or not?”

In St. Louis last weekend, [more than 100] prisoners in what they call the Justice Center, downtown in jail, broke open the door and started lighting shit on fire, holding up signs that said, “Free 57.” They were trying to bring attention to the 57 people being held in solitary confinement—and right across the street, people are having beers and pretzels.

In 2015, 2016, when healthcare was getting voted on, and they were trying to destroy Obamacare, disabled people protesting in power chairs and wheelchairs were getting ripped out of congressional buildings. They designed that protest in a way that was literally putting their chairs and their bodies on the front lines. Those are moments that should shock society into thinking about a new world.

Annika: Thinking about how we take up space in digital realms, facial recognition technology has been used to identify suspects in policing. But as former Google AI researcher Timnit Gebru [who was scandalously fired in December 2020] discovered, Black faces, faces with melanin, are not recognized by facial recognition. That’s the technology used by police systems to incriminate more Black people, and it literally can’t see us.

Liz: What does it take for somebody to feel safe? In built spaces, there’s the entity overseeing policy or management that sees safety as professionalized security companies and systems. But it’s important to disrupt that dynamic. Safety is about who people are in relationship with; who do they care for or feel cared by; and making sure that it’s not just receiving, but it’s also giving. In a lot of the communities that I work with, it’s like, “How do we better connect you?” Once you do that, you create conditions of stewardship and interdependence. We don’t need to be dependent on control to enforce it.

Niki: One of the interesting points is we barely have to say the term “policing” in this entire conversation, because we understand that policing, the carceral state or police state that we live under manifests in so many subtle, overt, visceral, and imaginative ways. One of my own commitments this year is challenging what folks think abolition is challenging in the first place. We’re not just talking about cages, police, and jails. We’re talking about how forms of policing show up everywhere in our lives.

Assata Shakur said, “We have nothing to lose, but our chains.” We’re in that juncture right now.

Sowing Seeds of Change

Niki: We’ve talked about a lot of harsh and violent systems, and shared experiences around how they impact our lives and the lives of those that we love and folks that we’re in solidarity with. But I also believe that in times of crisis and rupture, there’s always opportunity. 2020 definitely showed us that. And 2020 is over as a year but the crisis goes on. So what seeds are you sowing in this time of ongoing struggle? And what does dreaming actually look like for you right now?

Annika: I love this question so much, Niki. I feel like my dreaming right now is really just seeing this not as this far-off fantasy, although maybe it is far off, but not seeing these ideas of what can exist beyond white supremacy as something that will never be, but as something that’s well within reach, and how I can be stretching toward other people’s dreams. Not seeing my hopes as these individual, protected things that I have to keep secret, but how I can be communally reaching toward other people in ways that are authentic, and that are actually calling in change. Trinh T. Minh-ha wrote this really beautiful work asking, “how can we recreate without recirculating domination?”

So my dreaming is about, “what does that creation look like, and how can I be bringing other people along with me?” A lot of it is about healing, and really slowly and sustainably and intentionally, because I think slow and sustainable is very against everything that the capitalist systems we’re in preach. I am dreaming about how I can really slowly and sustainably reach toward other people’s dreams and heal this past trauma, which ends up being individual and then stretches toward the communal.

Liz: I love that. I find so much resonance with it. Arundhati Roy wrote this great piece at the beginning of this summer called, The Pandemic is a Portal, about the idea that normal didn’t work for any of us before this and we all kind of made do with it, because it seemed like, well, we’ve got what we’ve got and we’re just pushing against that. But this idea that within this, there’s a space to break from the normal, to see the critical harm of the normal, and to finally break free and say that it’s not about a return to that, because none of us benefited from it, and it harmed all of us.

The work that I was doing pre-pandemic continues with renewed vigor, but there’s a way of coming to terms with how, even in the work that I’m doing or have been doing, there’s still a complicity with the harm that I’ve done just by virtue of not fully de-programming myself of the ways in which I embody white supremacy. There’s an individual journey of understanding what that means, which could be as simple as, it’s okay for me to rest. Or, I don’t have to define success on these terms. Right? I can’t fully break the complicity and harm out in the world unless I also break it within myself. So there’s a big seed of nurturing around that.

Out in the world, I feel like the systems of oppression are dying an ugly death, but they’re dying. And so I’m looking at what it means to guide that death and to help support and protect the communities that have been most harmed by the system and are actually still being the most harmed as this thing is dying. And then dreaming of what’s beyond, what we can’t see, but we can feel. I’ve been trying to trust myself more to feel into that future and to feel into it with others. I really do believe that this interdependence and care are the foundations of whatever it is that we’re heading toward. So I’m constantly challenging myself to lean into that as much as possible as I take each step into what’s coming next.

Ivy: I’ve been spending a lot of time in nature—being inspired by the whole mycelium network—you may not see it above ground, but there’s a whole network or system that’s feeding all the plants, all the trees, and being able to send resources or nutrition through that network. Finding inspiration with that has been very helpful, and understanding that we are part of a legacy of our ancestors that has also nourished us. For the folks that have been doing this work for a long time, we are part of this longer arc of transformation. I’m excited to be a part of that network, of cheerleading other folks that are also doing the work, and cultivating my own connection to ancestors—this asset I always had that is just now becoming more and more apparent. Being able to thrive in a pandemic is such a feat. So that’s my dreaming.

Dustin. I don’t have a lot of hope for the situation we’re in. I think we’re in dire straits, and it could get worse unless we do something about it. The work of disability justice is not only a moral guide or a moral compass, but also very pragmatic. It’s about expanding and growing our movements, our capacity to bring more people in, and I think we need that right now. I think we need more polarization. We need more people to say we’re anti-fascists and to actually struggle against the state and corporations, but to do that, we have to have places for people to plug in.

Access is central to the way we organize and gather. Mariame Kaba says, “Let this moment radicalize you rather than bring you to despair.” I just come back to that a lot. I don’t have any poetic or deep words for it, but I think it’s just enough to say what is calling on us right now. Ivy brought up, just, the pace. So what I’m doing right now is what I was doing before, but just more intense, thinking about the pace in which we move, for whatever reason that we’re moving. And attempting to operate as if no one’s going to be left behind.

In operating that way, it is running counter to all of what white supremacy tells me is urgent, whether it’s fast food, fast fashion, eight-hour work days, whatever that is. I think about enslaved folks being on plantations together and singing a song to the same rhythm. Nobody is over-producing and nobody is under-producing, and everyone is ensuring that there’s going to be no punishment at the end of the day, because everybody’s moving at the same pace and trying to find ways to do that in every aspect of life. So my focus is pacing and ensuring that nobody’s left behind. Because we need all of us, as many of us as we can get.

Niki: Thank you for sharing all of those hopes and longings. I want to close this off with a thought from Ruth Wilson Gilmore that I think articulates what each of you is up to. She reminds us that, “Abolition is not about absence, but rather the presence of life-affirming institutions.” I think all of y’all are up to bringing those life affirming networks into fruition.