Cultivating a Counter to Climate Change

Regenerative Practices in Agriculture

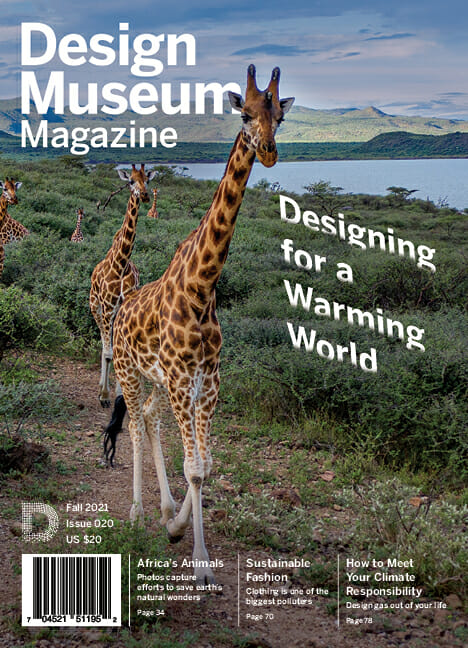

Photos by Leia Vita Marasovich

A conversation between Jonathan Anderson, Human Centered Design Practitioner, and David Leon, Co-founder and Executive Director, Farmer’s Footprint

In the following conversation, Human Centered Design Practitioner and CoDesign Collaborative Council Member Jonathan Anderson leads a conversation with David Leon, the Co-founder and Executive Director of the Farmer’s Footprint, a coalition of farmers, educators, doctors, scientists, and business leaders aiming to expose the human and environmental impacts of chemical farming and offer a path forward through regenerative agricultural practices.

Jonathan and David discuss the pitfalls of traditional commercial farming, what can be done to combat the negative impacts of farming on the environment, and how designers can get involved in catalyzing the change that is necessary to promote sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices into the future.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jonathan Anderson: I am thrilled that we are able to have this conversation, because this is an opportunity for us to put some really good information out there that allows people to reframe the way that they see some of the challenges that we face around climate, agriculture, and human health. And to begin this information exchange, David, I would love for you to introduce yourself and talk about Farmer’s Footprint.

David Leon: Absolutely, so I serve as the Co-founder and Executive Director of a nonprofit called Project Biome; the front-facing program is called Farmer’s Footprint. We founded the organization in 2019, with the initial inspiration coming from my co-founder, Dr. Zach Bush, who’s a clinical physician, was a cancer therapies researcher, and has worked in academia. When Zach transitioned out of cancer therapies research, he started a rural clinic in Virginia and he noticed right away that there was a lot of chronic disease in those populations. He was working with nutrition as one of the main ways that he was treating those patients, putting them on plant-based diets in an effort to lower what he understood to be high inflammation markers, perhaps coming out of the food that they were consuming. However, even with the healthier diet, he was actually seeing inflammation markers increase, in some cases. That got him really curious about what was going on with the produce that they were eating.

To find some answers, he started to look into food production. Specifically, he looked at glyphosate, which is probably the most ubiquitous herbicide that’s used in modern agriculture. He began his analysis along the Mississippi River and started measuring the water for glyphosate. His full grasp of what was going on really came to fruition, though, when he started meeting some of the farmers along those systems. What he found was farmers grappling with the effects of modern agricultural practices—the changes that they were seeing in their land and that they were feeling themselves. Zach found communities trapped in a prescriptive, big-agriculture paradigm, where someone comes out to the farms— the equivalent of a pharmaceutical rep—runs some tests, and prescribes farmers a slew of inputs to treat the problems that were in the fields.

For the farmers that want to transition from this system, they often face stigma in their communities, and really grapple with the internal tensions of, “This is everything I was taught not to do. I was taught to trust the science on this. We have all of these chemical inputs that produce green plants and increase yield. And this was supposed to be the right way to do it.” However, they are now seeing that, year after year, those input costs increase, the soil is unable to sustain production that it once was easily able to do, and there is an ever increasing need to add more and more fertilizers and pesticides.

We saw this tension between the scientific community trying to explain all of these complex relationships going on between the plants, the soil, and the human microbiome, and there is still so much work to do on that front. We’ve unleashed a massive number of chemicals at a population scale, in a very uncontrolled scientific experiment that we’re all a part of, unwittingly or not.

The goal of the Farmer’s Footprint is to tell the stories of these farmers that would resonate with people—we are all attached to this, and we all have a stake to play. We’ve gone about building a robust public platform and media organization that humanizes farmers and shares regenerative practices, and the way that this line of thinking can alter individuals’ mindsets and health, their communities, and the landscape. We sought to develop a mission that would radically scale adoption of regenerative transition. We focus on public awareness and scaling education for stakeholders in those value chains. We also work on scaling the economics of a region; scaling the dollar amounts of investable capital that can come in and meaningfully be deployed on the ground in service of this transition that we’re undergoing. We have a multi-trillion dollar food, agricultural, and industrial complex that stands at the precipice of a massive shift in the way that it approaches its work.

We created an organization that’s about progress over perfection. We’re not demonizing the farmers or the corporations for the practices that have come to be over the arc of history. We strive to create a space that is free of prescriptive solutions and more about collaborative co-creation. That means remaining agnostic as it relates to certification paradigms that have largely stratified access to food and have not delivered the economics to farmers that was promised. We need to create spaces for first steps, small steps. And then from there, we need to find those pressure points that will radically shift systems. That’s what we’re focused on, on a day-to-day basis.

JA: One thing that strikes me is that the process to transition to regenerative agriculture is not as simple as turning on a switch and making the change. I think one of the major impediments that I’m seeing is not so much the actual physical work in the transition. Rather, it’s the actual people part of it— enabling farmers to make that transition and step out beyond the system that they have now. Is that something that you’re seeing, as well? That it’s not only about being educated, but also it’s trusting to make that leap and take that transition period, which could have an impact on revenue.

DL: That’s absolutely right. We often cite that the biggest barrier to transition is between the farmer’s ears. And that is not entirely fair, either, because it’s not just the farmer. There’s a whole system around them, including processing, logistics, CPG, and consumer tastes. There’s a lot of shifting that needs to happen, and a lot of it is in this ingrained mindset, in organizations, and in the public. This is why we unabashedly pursue the storytelling strategy.

As an entry point for the design audience, I often think about the work that we do as deeply searching for metaphor. I think the best designs allow us to see or understand something in a way that maybe had not landed previously, or doesn’t land just in reading a book or being exposed to a TED talk. It’s this concept of, “How do you have an embodied sense of what this agricultural actually means?” Metaphors can be really valuable tools for seeing something through a different lens, a lens that, perhaps, has relevance to us in our day-to-day lives, but isn’t the obvious choice to go to in a farming context or a food context. We need folks with deep design experience that understand the process that it takes to actually change cultural norms and mindsets, which I think a lot of designers have great potential to be contributing to.

It’s become clear to us, with the organizations that have been in the space, working on the science, and producing some really exciting results around what these practices can generate, that despite this progress, the knowledge accrued hasn’t broken into the public sphere in a way that is truly embodied and felt. In order to get people on board with this and get their expertise in front of the challenges that that incumbent community is facing, we need to also extend to designers an invitation that says, “The expertise that you’ve built, building giant brands or producing art that moves culture—we need that same expertise in service of this work.”

JA: It’s as simple as that. In my research recently, I have seen a general takeaway that we don’t need extremely complex systems to farm. Regenerative agriculture is really mimicry of nature. Of course, market gardening doesn’t exist in nature, but we try to mimic it as much as we can. The real point here is simple tools and processes can make the farm more efficient and reduce the cost. But that initial transition can be a little bit challenging, because in that transition, the systems have to recalibrate and equalize. Rather than looking at the dirt as a medium to grow plants, we’re actually looking at the microbiology in the soil to then grow the plants. It’s just a different shift. We’re becoming soil farmers instead of just farming plants. It’s a holistic system that we’re looking at.

DL: Correct, and I think what regenerative practices show us is we need to start reorganizing our ways of being in organizations and in relationship with one another to one of deep collaboration. As you get into the complexities of the microbiome and the incredible consequences that come out of that diverse collaboration, you start to wonder about some of the things that we’ve taken for granted in nature.

That’s what nature is screaming at us to come and figure out. When the system is out of balance, we no longer have all that nature can produce. In its own brilliance, the land has provided all of the tools for us to have incredible abundance on the output with less input. We need to get into that cycle. We need to get back into that rotation. We’ve separated ourselves from it, and it is no longer serving us.

JA: It’s like the earth’s respiratory system is out of balance, and we’ve got to help right the ship. In the summertime, at least in the northern hemisphere, the impact, from what I’ve read, is that when the leaves are out and everything’s green in parts of the world, the levels of carbon in the atmosphere drop. But the problem is, this is not a healthy system; it’s broken down. And we’re seeing the impacts of climate change all around us. I wanted to put that out there to see what your thoughts are around it.

DL: I am glad that you brought up the topic of carbon levels, because I’m a little bit worried about the pervasive approach to climate change as being solely focused on sequestering carbon. Carbon is just one of the elements that must be addressed. Yes, we’ve focused on it because it’s easy to see and comprehend the negative impact of the accumulation of CO2, but it is one of many cycle centers that is in trouble in our landscape.

I have recently been struck by the way that nature moves in cycles all around us. For instance, the cicadas that we saw this year that have emerged from their 17-year cycle are a very visual representation of a long-form cycle. Everyone knows, “Oh, it’s coming, and there it is, and oh, my gosh. This is ridiculous. There’s so many bugs.” Imagine what cycles we don’t even see because of the time or scale that they’re on. So in addition to these shorter-form cycles of carbon moving through at a seasonal or daily rate, we have to think about water cycles, nitrogen cycles, and so much more. What landscape-level cycles are happening over hundreds or thousands of years that we treat as a blip on our radar for the blink of an eye that we’re on earth?

We’ve created a system fitting in productivity in a way that’s expedient for capitalism to work well, and this has been one of the downfalls of modern agriculture. We have had a laser focus on annual yield, instead of where the roots of regeneration really come out of in indigenous thought, which very wisely looks at seven generations of impact, that every year is just another step in a much longer cycle. We must observe and listen to the land and allow what we’re seeing to teach us, to give us clues about where we are, and to react responsibly and compassionately with what we’re seeing coming out of those cycles. Every time we look up and we reflect for a moment on the phase of the moon, or where the tide is today, or how the winds have shifted due to the seasonal changes or the currents in the water, these are all invitations for us to jump back into these natural cycles in a way that is ingrained in our DNA, because we have coevolved alongside the breathing of this planet.

So let’s be very careful about just focusing on just carbon. Or at least let’s acknowledge that carbon might be a moment of triage that we need to address today and urgently. Let’s not pretend that sequestering it, that putting it down deep into the ground and hoping it stays there, is what we’re ultimately after. We need to go after a balanced system once again. And that’s going to take a lot more humility than I think we’re currently approaching with some of these solutions.

JA: That is a great point, and I think we also hear the term sustainability being thrown around a lot. To me, what sustainability says is that it’s about maintaining the status quo. So I think in addition to promoting sustainability, we need to move beyond and strive for the land to end up in a better place after we’ve interacted with it. It’s not about me forcing it to go in the direction I want it to be. It’s about being the shepherd or the steward of that land, and then allowing nature to run the show. If we can do that, I think we can have a much more productive and much more balanced way of living.

DL: I love that notion, and I think what comes to mind is the idea of the tribe figure, which is the average of the five people that you spend the most time with. I would encourage people to reserve one of those slots for being in relationship with the environment. You don’t have to have access to go out into an old growth forest or a jungle waterfall. It’s not just about that. You can look up in the middle of New York City and see the moon cycle happening, or see the cicadas descending upon you, and you can be in relationship with nature at that moment. Just imagine having a friend like that. Someone that you have a deep relationship with, that is an endless fount of innovation. We mimic the folks that we look up to and that we seek to become and learn from. What an opportunity, to be four people plus nature, because what can we learn from a knowledge source like that? And how is that going to make us better at our jobs, and better at being in relationship with our family, our community, and the land we live on?

I’ve come to start to define regenerative agriculture as relationship agriculture. I want folks to start to think of this term, not in just a set of discrete prescriptive practices like using natural fertilizer, but as an invitation to be in relationship with the farm, and that’s what stewardship really is about. If we can start to come up with that vernacular and metaphors for describing this relationship, we are going to have such a rich journey on the way to these regenerative practices. We need the best creative minds in the world thinking about how to make the concept of our relationship with the environment a tangible thing. I’m really excited to continue to get a lot of fresh ideas about how we can accomplish this, and storytelling has been one of those ways, because we can feel something artistically, poetically, that is not just the data on a page.

JA: This really excites me. It’s such an opportunity, because I think one thing that is missing in our culture right now is community. COVID, in a way, woke a lot of people up to that. We were all laser focused on our jobs, carting our kids all over the place, and when we came home at night, there was very little thought on interacting with one’s community. What’s happening now is this recognition that when the option to interact with the community is taken away, we then are able to see its value in our lives.

We have relearned the value of support, so that when my barn burns down, my neighbors are going to come in to help me rebuild. And if I have a crisis, there are people there for me. That’s the shift that I see regenerative agriculture having, it’s bringing that community back into play, and being in equal balance, too. It’s the idea of, ”I need to work hard, but I also need to collaborate and work along with my neighbors and friends. It’s not just me out there by myself.” Nobody can have success in their life without other people helping them along the way.

DL: That’s right, and I point to something that Zach talks about a lot, that cancer, which he spent so long studying, is essentially a cell that has forgotten how to be in community with the rest of its system. A cancer cell is just any other cell, but it doesn’t perform its function in community anymore. You essentially have nonspecific multiplication of the cells that’s just substance. I think there’s a really important lesson there for us. We’ve seen cancer rates explode, and we need to extrapolate what is happening down at our cellular level, up through the population, landscape, and planet. Nature is demanding that we be in community with it and with each other.

We’re going to see, I think, really painful ramifications if we don’t find our way back to that very essential skill that allowed us to be so successful as a species on this planet. If we can choose to understand it, there is incredible abundance at the other end of that road. It may start with not tilling your field or planting a cover crop, but it ends in community prosperity. It ends in more mutual understanding. It ends in prioritizing how we want to live and be in the world amongst each other. These are the happy consequences that spiral out of regenerative agriculture, and what agriculture can teach us.

I’m so inspired that the farmer is set to be a model of this hero’s journey toward sustainable and regenerative practices that all of us are being asked to now go on. Those that are closest to the land, that have the highest capacity to perhaps be in relationship with that land, will lead us all to be in relationship with our place. And these places whisper at us. They whisper all sorts of signals that I think guide us to where we want to be.

I’ll say one last thing in closing. And that is again a call-to-action for the design audience. One of the pushes for transformation comes when we are facing existential threat. That’s true in addiction, it can be true in a health crisis, and it’s true for farmers. Many of the farmers who were the early adopters of regenerative practices did so because they were facing existential threats to their farms. They were going to lose the farm, or the farm was going to stop producing. The question is not, “Are we going to fix this?” The question is whether we want to be along for the ride going forward or not. That’s something that we all need to humbly accept—if we want to be here, changes are going to have to happen. The world is going to go on without us, and it’s going to be okay. So don’t wait for the world. We need to choose to listen to the signals that are coming out right now, that’s our challenge. We need folks who can design ways to amplify those signals. We need designers who are going to translate it so that it lands with as many people as possible.

Beyond that, we must think about how to make this transition happen before the farmer is facing that existential threat. A job for all of us, and especially the design community, is how we are going to make this transition before we’re in dire straits. We can avoid a whole lot of suffering if we can move more quickly. I think that’s just a matter of landing and embodying some awareness. I hope that that’s one of the things that touches readers, and I’m just very grateful to be able to share some thoughts with them through this conversation.

JA: David, thank you very much for your input, wisdom, and the work that you do. You’re telling stories that people can relate to, and that’s crucial, because if we’re just lecturing at people and telling them, “These are the steps we have to take,” it’s not going to land. It’s the stories that resonate with us, because we can see ourselves in the story. When I got involved with the community in Farmer’s Footprint, I met so many different people that have allowed me to start to see what my role can be in this work. Being in community with people, building those relationships, having conversations, and listening have all allowed me to check my preconceived biases and notions of how we can make a difference. This has enabled me to uncover the very thing that you’ve talked about here—it’s all about relationships. And that’s the exciting piece of it, because that’s within our control.

For more information about Farmer’s Footprint, please visit their website at farmersfootprint.us