Create Local, Launch Global

Onehundred is Ushering the Next Industrial Revolution

Long before industrialization and a global economy, nearly every product someone used would have been made by a local craftsman from locally-sourced materials. Can we learn from that model and make it work again today?

By Dave Laituri

I think about how far our products will travel and the satisfaction that will unfold when the package arrives at its new home. I never imagined I’d feel such joy mailing off a box, in which the contents are locally made, with a label designating the destination of a remote island, a small farm, or a mountain town above the treeline.

At Onehundred, we design and manufacture every single product, from benches to bird feeders, within 100 miles of Boston, launching each with our enthusiastic, international crowdfunding community.

Humble Beginnings

Every town in New England seems to have a community trade area – a social place, sometimes near the town recycling center where neighbors put the things they don’t want anymore to be picked up by those who do. This old rocking chair was put up for adoption in the trade area of our town’s recycling center a few years ago. Like most things there, the chair was ugly and covered in dings and chipped paint from multiple former owners; it was a classic trade area candidate.

Once the chair was stripped down to bare wood, though, it told an interesting story. It was lopsided and asymmetrical from birth, hand-carved using very few tools – none of which were powered. It was likely produced in the early 1800s, made by a moderately skilled craftsman for a nearby customer and built from locally-grown timber. Unlike a mass-produced chair today, it was not shipped from a distant factory in another country to a local store, found in a catalog or online, or liquidated at an end of season over-stock sale. The user knew the person who made it, they met face to face, discussed what should be built and probably shook hands upon delivery weeks later. The supply chain that brought it into existence was simple, direct and human.

(Re)discovering our Neighborhood

With my experience designing and manufacturing hundreds of products overseas for startups and Fortune 500 companies alike, I had some questions after thinking about the story behind this 1800s rocking chair: can we still make things here in our New England neighborhood? Could we replicate this process in the twenty-first century?

Those were the big questions back in 2012 when we founded Onehundred. We wanted to challenge ourselves to see how much we could make locally and to test selling those local products on a global market.

Anyone who has spent time in New England is at least peripherally aware of “Yankee Ingenuity” – that 200-year-old idea of self-reliance and making do with what you have on hand. It’s about improvisational design, to understand what you are able to make before you try to make it and being resourceful along the way. Onehundred’s mission is an update of that idea: Yankee Ingenuity 2.0. Our name, Onehundred, stands for the 100-mile day trip radius around our Saxonville, MA studio that dictates what factories and shops we work with to produce our products.

Onehundred’s process is simple: find talented local shops and factories, design products that fit their capabilities, and bring these products to the global market. Our global market is located on Kickstarter, an online crowdfunding platform. On Kickstarter, to receive the crowdsourced funds raised, you have to reach the stated goal. If we don’t reach our goal, we don’t build the product.

In the first five years of this experiment, we created 110 products with 40 local factories and shipped them to over 80 countries worldwide. 99% of our revenue stays within our 100-mile boundary. 96% of what we manufacture is shipped out to the world. We have the smallest possible ecosystem to work with – only the product creator (us), the product producer (our chosen shop), and the product user is at the table. Like the 1800s rocking chair, products are only manufactured when desired by our customers. The unique combination of our local manufacturing mission and our global crowdfunding backer community drives our production decisions.

Being centered in New England, the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution and a center of the tech industry, there is a unique and historical mix of talent in our neighborhood to work with; 100+-year-old, family-run factories can be found alongside cutting-edge technology shops with the latest computer-controlled machines.

Every shop we’ve worked with, new or old, has an interesting story of their own, but it’s the ones that have been around the longest who still use historic machinery and processes that tend to stand out.

Take the Pepperell Braiding Company in Pepperell, MA, for instance. Founded in 1917, they started out producing candle wicks and shoelaces for the thriving regional shoe industry. Originally powered by the flow of the adjacent Nashua River, the factory still produces braided nylon paracord for the craft market on converted belt-driven braiding machines from the 1890s. A ballet of spinning spools, they are mesmerizing to watch. Early machines like this were both simple and complex at the same time. What could we do with braided string? It took about three months before we had an answer.

Flat, fold, feed…

A summer breakfast conversation with my then 14-year-old son and co-founder, Calvin, turned into an idea for a line of bird feeders. He was very interested in origami at the time, and we had dozens of paper cranes all over the house. The idea: create a bird feeder that arrives flat like a greeting card, but easily folds into shape. We made a quick mock-up on our kitchen table out of the cardboard from the back of a notebook, a dowel, and a borrowed bootlace. Then we filled it with seeds and hung it outside for a test.

Within ten minutes, we learned that birds jump when they take off, flipping the prototype and sending seeds everywhere. With a bit of re-working, we were able to stabilize the design for a re-test. This time the seeds stayed put and we had found that purpose for string we were looking for! A week later we had bendable aluminum prototypes. The Kickstarter campaign that followed was a success, and we shipped them out to our Kickstarter backers soon after. The entire process took five months from kitchen table to worldwide shipping.

What’s next?

Spending time working with local shops has been very rewarding on its own, but it’s also brought up some interesting new thoughts and insights along the way. We’ve learned a lot about the subtleties of local production – how it stacks up against manufacturing in China and what its future potential holds. For instance, take the locavore movement – choosing a diet based on locally-grown foods. Could there be a parallel local-made movement someday? While we’ve been pleasantly surprised by how many everyday objects could potentially be produced nearby, there’s not enough manufacturing diversity in U.S. neighborhoods to make everything. But, a much healthier blend of local and imported goods is certainly possible.

One of the more surprising discoveries is that our carbon footprint is considerably lower for each of our products versus producing them in China – about 62% lower on Tuls and about 80% lower for Blox, two of our other products. Since we’re down the street from our entire supply chain, carbon created by shipping raw materials and finished parts is almost non-existent.

To produce something made of walnut in China, the milled lumber has to be shipped from where it grows in North America to a factory in China where it’s turned into a product. The product is then shipped back to the U.S., resulting in at least a 15,000-mile round trip. That’s a lot of embedded train, truck, and container ship-generated carbon. By working with local lumber suppliers, we’re able to select the ones who source their walnut as close as possible to our shop.

Taking the Onehundred idea one step further, we imagine one day expanding the company globally – a Onehundred LONDON, Onehundred TOKYO, Onehundred CAPE TOWN, and other cities that have unique neighborhood manufacturing qualities of their own. We’ve also imagined using the Onehundred model to help in community revitalization, combining local manufacturing capabilities, entrepreneurship, and design with local and global demand to change a neighborhood’s “balance of trade,” importing much-needed revenue while exporting products, creating new jobs, and energizing new businesses along the way.

As our 1800s chair can attest, local manufacturing is certainly not a new idea, but nonetheless, an important system to revisit. We still have this chair at our house. Whenever we see how much less expensive it would be to manufacture a new product beyond our 100- mile radius, the chair reminds us of the value and the rich stories of local production.

From Design Museum Magazine Issue 009

Make Local

Howard Precision

The decedent shop of Howard Clock was one of the first that we met on our journey. Located near our studio in the Saxonville Mills, they were founded in 1845 and produced watches and clocks of all sizes, eventually becoming a precision CNC lathe shop in the 1950s. When we met them in 2016, it was the sounds and smells of their shop that hooked us; we had to come up with a project together. Our stainless steel whiskey stones, Pucs, were the result.

Henry Perkins Company

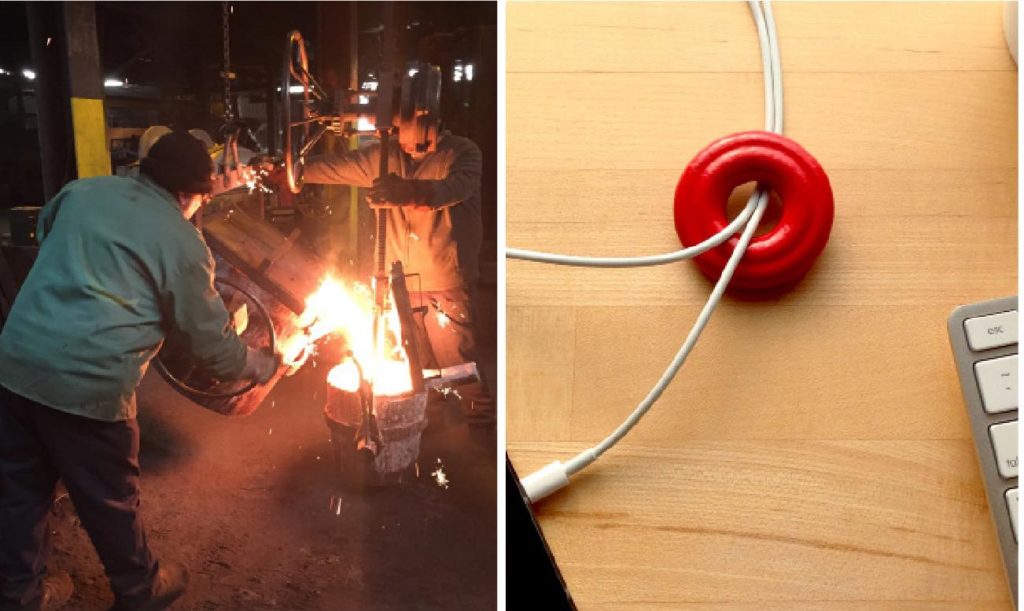

This iron foundry in West Bridgewater, MA, is another personal favorite. Dating back to 1849, they have been continuously run by five generations, originally producing cotton gin parts and grey iron piano plates. Iron casting dates back to the 5th century BC, and while furnace technology for melting iron has evolved considerably, it’s still very similar. Two months after a tour of the casting floor and their pattern shop, we came up with a simple product called Bagl – a paperweight for organizing charging cables.

R. Murphy Knives

Founded in 1850 in Ayer, MA, R. Murphy originally produced surgical and dental tools, but currently manufacture a wide range of high carbon steel knives for home, commercial, and industrial applications – leather knives for the shoe industry and oyster knives are their specialties. We hadn’t thought about designing a knife, but after meeting, we were determined to add one to our line. Fave is the result – a line of contemporary utility knives with high-carbon steel blades.