Closing the gap between user experience and policy design

Civilla, a Detroit-based nonprofit, worked on a human-centered redesign of the City’s 40 page application for public benefits. The process resulted in a streamlined application that was 80% shorter and could be processed in nearly half the time.

By Cecilia Muñoz, Senior Advisor, New America & Nikki Zeichner, Product Director and Civic Technologist

Ask the average American to use a government system, whether it’s for a simple task like replacing a Social Security Card or a complicated process like filing taxes, and you’re likely to be met with groans of dismay. We all know that government processes are cumbersome and frustrating; we have grown used to the government struggling to deliver even basic services.

Unacceptable as the situation is, fixing government processes is a difficult task. Behind every exhausting government application form or eligibility screener lurks a complex policy that ultimately leads to what Atlantic staff writer Anne Lowrey calls the time tax, “a levy of paperwork, aggravation, and mental effort imposed on citizens in exchange for benefits that putatively exist to help them.”

Policies are complex, in part because they each represent many voices. The people who we call policymakers are key actors in governments and elected officials at every level from city councils to the U.S. Congress. As they seek to solve public problems like child poverty or improving economic mobility, they consult with experts at government agencies, researchers in academia, and advocates working directly with affected communities. They also hear from lobbyists from affected industries. They consider current events and public sentiments. All of these voices and variables, representing different and sometimes conflicting interests, contribute to the policies that become law. And as a result, laws reflect a complex mix of objectives. After a new law is in place, relevant government agencies are responsible for implementing them by creating new programs and services to carry them out. Complex policies then get translated into complex processes and experiences for members of the public. They become long application forms, unclear directions, and too often, barriers that keep people from accessing a benefit.

Policymakers and advocates typically declare victory when a new policy is signed into law; if they think about the implementation details at all, that work mostly happens after the ink is dry. While these policy actors may have deep expertise in a given issue area, or deep understanding of affected communities, they often lack experience designing services in a way that will be easy for the public to navigate.

Often this is the case also with those at government agencies tasked with translating policies into programs that will serve the public, though this is changing. For example, when San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors passed an emergency multi-agency program enabling local restaurants to expand operations to outdoor public spaces, many struggling restaurants couldn’t get through the application process. “Their intentions were in the right place but each of the agencies involved had different responsibilities and none of them were centered on the business owner or the user,” a City employee who had worked on this project recalled. They explained that when the program initially rolled out, business owners struggled to understand how to answer the questions in the permit application form. “The regulations themselves are really unclear because so many different departments have jurisdiction over this space. The Municipal Transportation Agency (MTA) has certain rules. Fire has certain rules. Public Works has certain rules. The Planning department has certain rules. When we interviewed business owners, they said that understanding the guidance was much harder than the form itself.”

This is why many of the policies written to provide benefits don’t end up actually reaching the people they were intended to serve. Consider the complexity of tax filing: most people in the U.S., regardless of income, pay for tax preparers or commercial software to file taxes every year. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), recognizing this problem, funds free access to tax preparation services through the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program. But even after decades of offering this help, as of 2018 only 3% of the 100 million families eligible for free tax assistance actually used the service. The IRS also sought to make free online tax preparation available for low income individuals through a public-private partnership called the Free File Program.

However, people had trouble finding and accessing it. The tax prep companies, which had hoped to lure new customers out of this service, stopped offering free online filing services altogether, leaving the IRS and millions of low income filers in the lurch. Other well-intentioned policies have similar barriers to impact: states with paid leave policies, for example, rarely reach even half of the eligible population. The Unemployment Insurance systems in many states notoriously buckled when they were most needed for workers who lost jobs during the pandemic. “The process was crazy. It was a full-time job for a number of weeks…” said one engineer of his experience applying for unemployment. He was interviewed in a joint study of the lived experience of applying for benefits during the pandemic to make the pain visible to lawmakers, who were debating the size of the benefit, but who were less focused on the experience of users accessing it in the summer of 2020.

Gaining traction in government

Getting a new policy passed is a lot of work—this alone is reason to celebrate when a president or governor signs a new law. But when a policy gets passed the actual victory is not the law itself, but its impact on people’s lives. Someone needs to be involved in the early stages of policymaking who brings deep expertise in designing services that are simple to interact with. People’s lives can depend on it. Tara McGuinness, founder of New America’s New Practice Lab and her co-author Hana Schank, in their book Power to the Public, make this case:

Economists and statisticians are pretty good at answering questions like How much will it cost the government to pay for this? or How many families could be eligible? But the current tools are not particularly useful for understanding the needs of a population, nor are they helpful in assessing in real time whether a policy is working the way it was intended.

Those who know how to design and deliver products and services that are easy for people to use are moving closer to the policy table organically. Code for America, a nonprofit organization founded in 2010, has played a key role in making the case for improving the user experience of government programs. It’s been almost a decade since digital services teams like 18F and the US Digital Service (USDS) began doing the same by giving federal agencies easier access to user experience design services (these teams were born of the national crisis around Healthcare.gov). There are numerous examples of civic-minded companies serving the public sector like Nava, Adhoc, and Skylight. Delivery efforts at the state and city level are expanding as well, including numerous state digital services from Georgia to New Jersey and Colorado. These teams are demonstrating that public services need not force people to jump through hoops to access what they’re eligible for.

Federal agencies have been increasingly focused on user experience design as well. One impactful example is the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice’s partnership with 18F to develop an easy, online process for the public to submit civil rights complaints, simplifying a process that was previously difficult to navigate. And the Government Accountability Office (GAO), known as the “congressional watchdog,” recently issued a report on the IRS’s Free File program, in which it calls for the IRS to incorporate “experience improvements” to improve its delivery and its reach. Code for America has introduced a framework for delivery and policy teams to work in partnership. Georgetown’s Beeck Center recently published an assessment tool to help policy makers understand how to think about social impact during the policymaking process. Our colleagues at New America have also written about this topic.

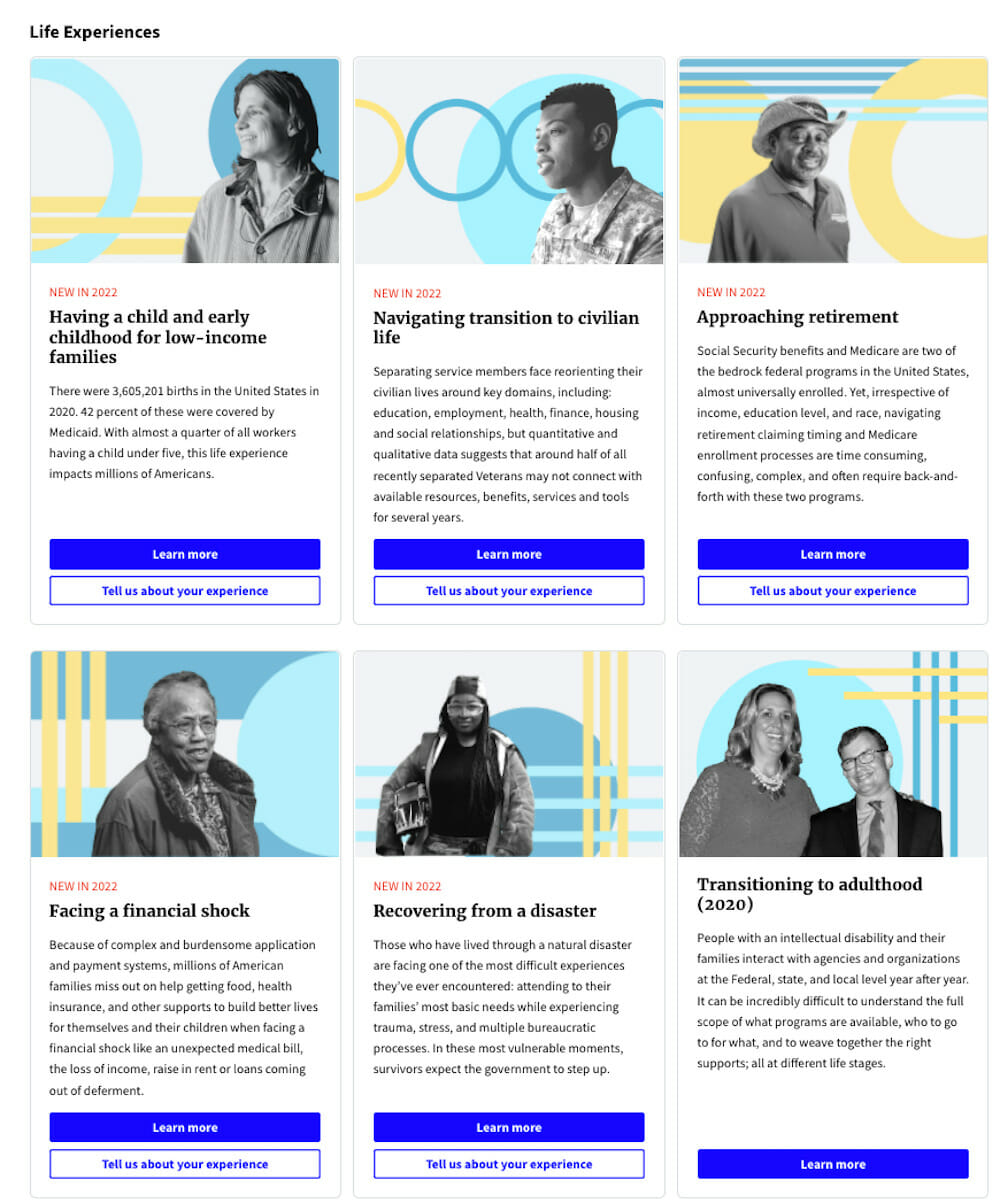

The idea of policy making and user experience design as interdependent partners has continued to gain traction, particularly after the pandemic highlighted the broken infrastructure of many social safety net programs. At the tail end of 2021, the White House issued an Executive Order calling for agencies to put people at the center of their services. The language in this order references digital design methods as ways to strengthen democracy, narrowing the distinction between policy making and delivery implementation; between the substance of laws and the way that people experience them. “The Federal Government must design and deliver services in a manner that people of all abilities can navigate. We must use technology to modernize government and implement services that are simple to use, accessible, equitable, protective, transparent, and responsive for all people of the United States,” President Biden said when introducing this EO. In April the Wall Street Journal reported that teams would look not just at government programs but also look at “life experiences” examining key moments like approaching retirement, recovering from a disaster or giving birth to a child.

A two way street

These are hopeful signs of progress, but there is much room for improving how policy gets made in the first place. Bridging the gap between policy and user experience design goes two ways: while policy makers are beginning to bring user experience design closer to their practice, user experience designers are also beginning to learn how to effectively present their work for policy audiences. “That’s a big part of the practice that we’ve had to build,” says Lena Selzer, one of the founders of Civilla, a Detroit-based nonprofit committed to transforming public-serving institutions through human-centered design. Civilla is best known for having redesigned Michigan’s benefits application form, which had been the longest in the country before their work. “Researchers and designers who work in complex institutions have to learn how to negotiate between what users need and the very real constraints of the institution, the funding and policy requirements,” she explains. We see this too in our own work with the New Practice Lab, a small non-profit policy and delivery startup housed inside New America, that works to move these delivery learnings upstream so policymakers can see the lived experiences of those using policies. A key part of this practice is user research, which happens in partnership with government and nonprofit teams that seek to make safety net programs more accessible. Part of the challenge is to translate design insights into formats and language that are most useful for policy makers. If we create personas and journey maps as part of our process, for example, would policy makers want to see them? Or would it be more helpful to offer guidance in a form that policymakers are more accustomed to, like a bulleted list of our takeaways and recommendations for action? There’s still work to be done to translate the language of design and delivery into the language of policy making.

Today, there’s a distance between policy being made and policy reaching people. By closing this gap, we can strengthen what government delivers, and hopefully the trust that people place in their government. Better still, we might someday live in a world in which there are as many trained designers making policy as there are economists; combining long-term economic analysis with a nuts and bolts understanding of how people live and how they access what’s available to them. This is entirely achievable, and there is a growing field of skilled delivery practitioners, many of who think of themselves as public interest technologists, beginning to have an impact on how policy lands. The federal government and a number of states and cities are getting better at deploying them to tackle cumbersome bureaucracies from food assistance, to taxes, to COVID tests. We can get there, but first we must stop thinking of the user experience as a separate stage of policymaking. A functional democracy requires good laws that actually work to serve the public. The path there is not easy, but it begins with bridging the gap between policy makers and policy users. We have seen this approach succeed time and again: we just need more of it.

In April 2022, the Federal Government launched a new initiative to design public services around the needs that people have during select life experiences. This initiative was adopted to improve Federal service delivery and customer experience. Visit performance.gov to learn more.